The Civil War Era In Lower Merion

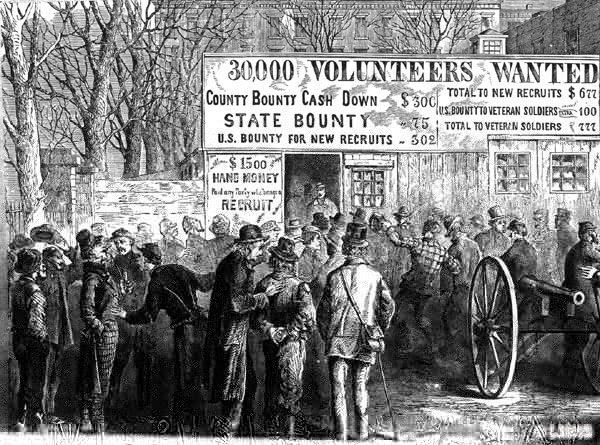

Volunteers Recruited

The Main Line was alarmed by the approaching Confederates and Philadelphia threw up earth fortifications (especially at the site of the 30th Street Station) and dug trenches.

In April 1861, President Lincoln issued orders for a militia to defend the capitol at Washington and 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion. Pennsylvania’s Gov. Curtin relayed the call to the cities, the towns, and the villages in his state. Lower Merion men were eager to respond. Most of the enlistees were farmers’ sons.

The state legislature passed an act for the organization of the Reserve Volunteer Corps to consist of 15 regiments: 13 of infantry, one of cavalry, one of artillery. The men were to be enlisted for three years.

Complying with the act, prominent Lower Merion citizen Owen Jones (1819-1878) began raising a company of cavalry, the first unit the county sent to the army.

Lower Merion was a good field for cavalry recruiting, since a large part of the population was accustomed to dealing with horses. Recruits were mustered into service in August 1861 at Athensville (the former name of Ardmore).

Owen Jones became a Major, then Colonel, and the regiment saw vigorous service with the Army of the Potomac and in the Shenandoah Valley.

Discharge Center

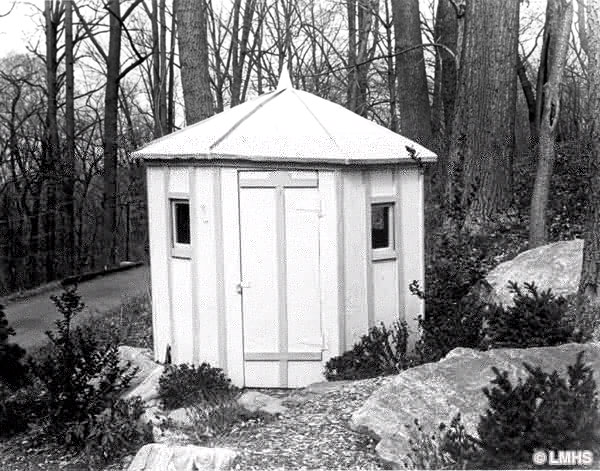

While the war was at its height, and the terms of many of the first enlistments were expiring, the U.S. government established the state’s mustering-out camp in Lower Merion in October 1864. The site selected was a summit on the west bank of the Schuylkill. The post bordered the locale of today’s Riverbend Environmental Education Center off Spring Mill Road in Gladwyne.

The area was at the crown of the hill above the houses on Kirkner’s Farm. The outlook commandeered a view down the Schuylkill River to Flat Rock, the Whitemarsh valley, and, in the other direction, a ridge with a view of Bryn Mawr beyond.

A large group of men levelled the rough, uneven surface. They then constructed a quadrangle of buildings with a parade ground facing the river. Water was piped from an old spring near Hanna’s Farm and transportation was over the Reading Railroad on the east bank of the river.

One month later (November 1864) the camp was ready for the reception of soldiers. It was christened Camp Spring Mill, but later known as Camp Discharge.

Many of the men being mustered out came from Andersonville and other southern prisons and hospitals and were in sick and miserable condition. Their records were put in order and pay was prepared as they recovered their health prior to discharge. No man was released until he was well, properly clothed, and provided for.

In July 1865, with the end of the war, the War Department disbanded the post.