Merion Friends Meetinghouse

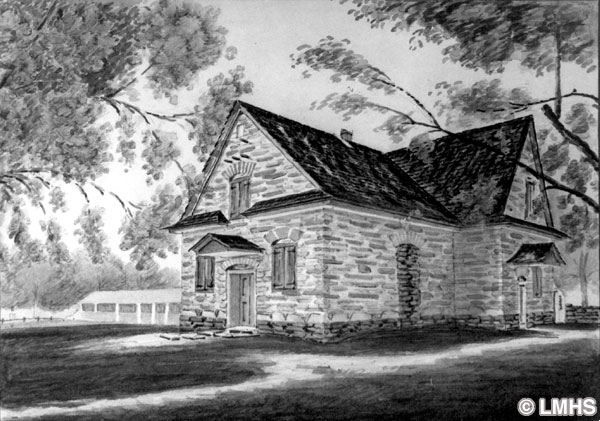

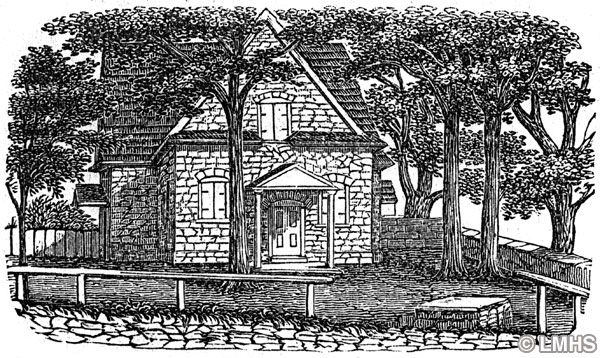

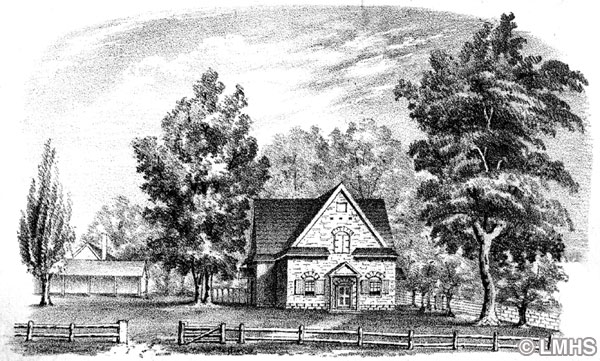

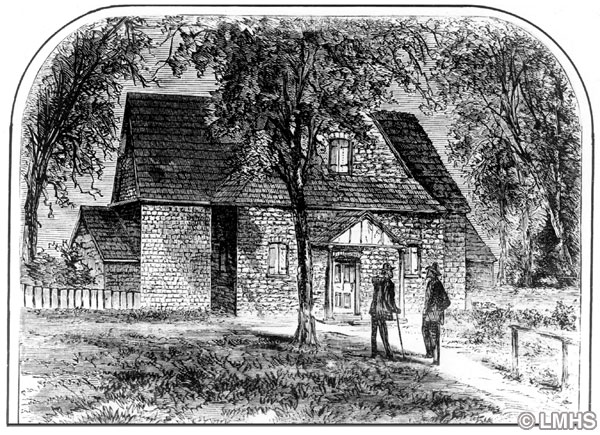

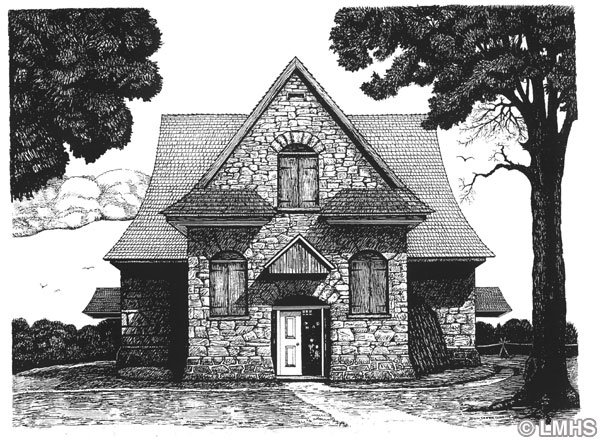

Merion Friends Meetinghouse has stood as a landmark for 300 years. It is the most pictured Quaker meetinghouse in America, was the first public building in the area, and in 1998 was named a National Landmark by the U. S. Department of the Interior. Not only does its age, largely unaltered design, and continuous use make it a notable structure, but also the fact that Welsh members of the Society of Friends who built it represent the earliest migration of Celtic speaking Welsh in the Western Hemisphere. These “Merioneth Adventurers” were not accustomed to building meetinghouses in Wales. In the homeland they were not even permitted to meet for worship in each other’s houses when being persecuted as nonconformists. So here in the freedom of America, they built what they knew, something like a barn or a house, with a loft up above to be used as a schoolroom.

In or before 1695, the Welshmen who constituted Merion Meeting contributed labor, materials, loads of stone and wood to construct a meetinghouse. First indication that it was ready for use is found in Monthly Meeting minutes which records that Daniel Humphrey and Hannah Wynne, youngest daughter of Dr. Thomas Wynne, were married “at the public meeting house in Meirion” on October 20, 1695.

Observable evidence suggests that the building was executed as a single unit, according to National Park Service historians, but not until investigative deconstruction or judicious archaeological work under the floor, can more be known.

Minutes of business meetings between 1702 and 1704, and again between 1712 through 1717, record assigned tasks such as “make a cupboard in ye meeting house to the use of ye meeting to keep Friends bookes or papers,” or “add hookes and staples to the meeting house windows.”

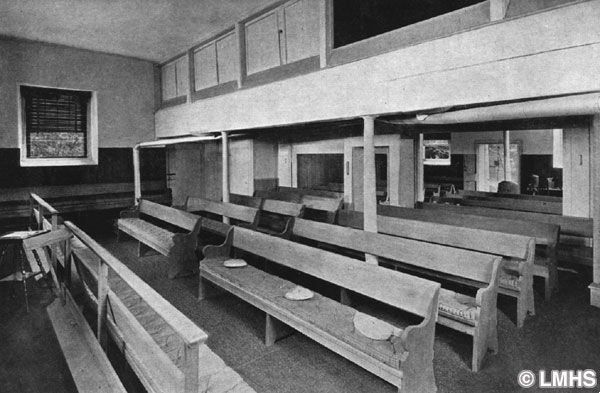

In 1702, Griffith John and Robert Jones were appointed to find a carpenter to make benches some of which we believe are still in use, originally made with peg legs and no backs, but now modified for comfort. David Maurice was to “secure the meeting house” presumably against bad weather. With such reference to the meeting house already existing, then why were members requested to “see for stones to build a meeting house in 1703, and were to be reminded to pay their subscriptions toward the building project”? Was there thought of creating another, larger meetinghouse?

It may have been at this time the second, larger room was added, wide enough to accommodate two enclosed staircases to a gallery where children sat, strictly divided girls from boys, with access through a low door to the schoolroom. The additional room made the building T-shaped but not cruciform, as is sometimes stated. The roof was a major expense in 1714. The floor, says tradition, was supported by tree stumps.

Analysis reveals that the present chimney was added later, jerry-rigged through the existing roof. Merion may have had a fireplace similar to the one in the Old Haverford meetinghouse (on Eagle Road in Havertown) with openings both inside and outside the building so that fuel could be added from outside without disturbing the silence of the meeting within. On December 16, 1798, we know a stove was in use from a note in Joseph Price’s dairy: “Whent (sic) to Meeting, had 4 preachers…no fire in stove yet was prety Passable as to Cold.”

In the larger, added room shuttered windows high up above a modern dropped ceiling are visible now from below. Partitions to be lowered when necessary separate the two interior parts, whereby the women’s business meeting could be held while the men’s was in progress.

These separate meetings were held until 1883, then combined. A row of nailholes in the wainscoting of the larger room, and hat pegs placed too high, probably mean there once was a higher level of “facing benches” where visiting Public Friends (preachers) and elders sat, men on one side, women on the other. In 1829 Friends tried to improve the exterior by plastering over the original stonework and scribing lines to resemble cut stone blocks. At this time, perhaps, a window or door on the east wall of the first room was blocked up for some mysterious reason, the outline still faintly visible under the plaster. In 1849 an arched vault over a chamber below ground off the east wall was built to hold bodies for burial until graves could be dug.

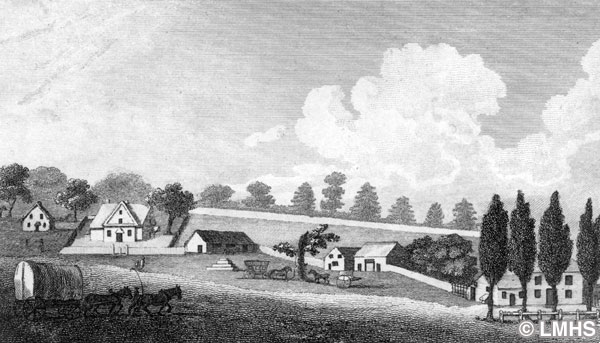

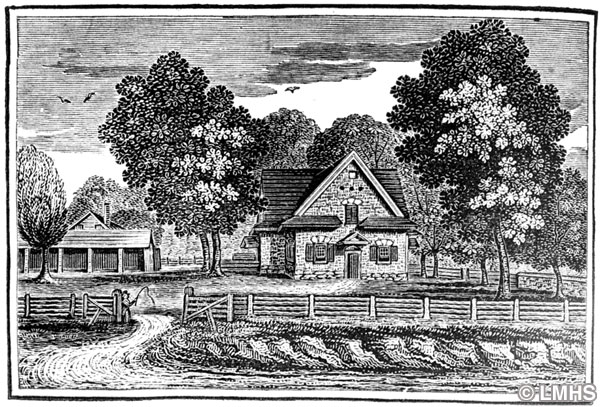

The existing sheds for horses and equipage were probably built in the 1820s, but “stables” were there in the 1790s, as mentioned in the Price diary. A faint depression of a sawpit remains where two men could saw beams for the sheds, and pieces of a very dilapidated stone mounting block lie nearby. A huge sycamore tree three centuries old stands near the gate to the driveway.

Meetings for worship are still held each Sunday at eleven, unprogrammed and without a pastor or visiting preachers. Silence is broken by occasional spoken ministry by worshipers responding to inspiration of the “Inward Light,” principal doctrine of Quakers, the sort of speaking which underscores basic tenets of Friends’ faith and practice, namely equality, simplicity, non violence and peace.

Merion Friends Burial Ground

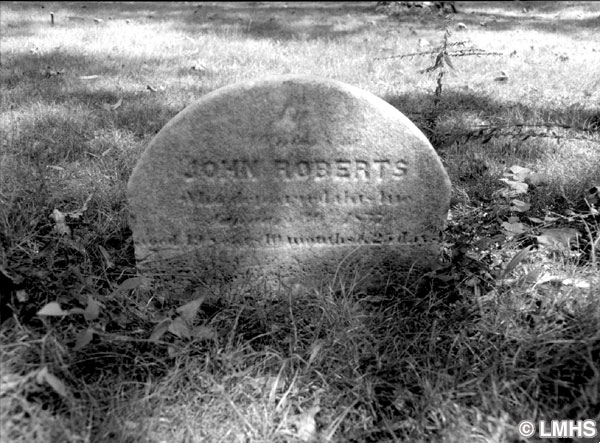

Where there’s life there’s also death. The subject of a burial ground in each of the four Quaker communities “beyond Schuylkill” (Merion, Haverford, Radnor and, only for awhile, Schuylkill) was broached in 1684. The two men from Merion, Hugh Roberts and Robert Davis, reported that Merion had a burying place, location not described. Possibly Hugh Roberts assigned a portion of his land for burials which may have included the place where Edward ap Rees (Edward son of Rees, eventually Prees, then Price) buried his young daughter in 1682, just two months after setting foot in the Welsh Tract.

In 1695, Edward Rees sold for five shillings a half acre to trustees of Merion Preparative Meeting for a burial ground and to them leased the adjacent plot where the meetinghouse stands. For 82 years, Merion Friends possessed the only place in today’s Lower Merion for burials. Everyone was accepted: Indians, strangers, servants, slaves.

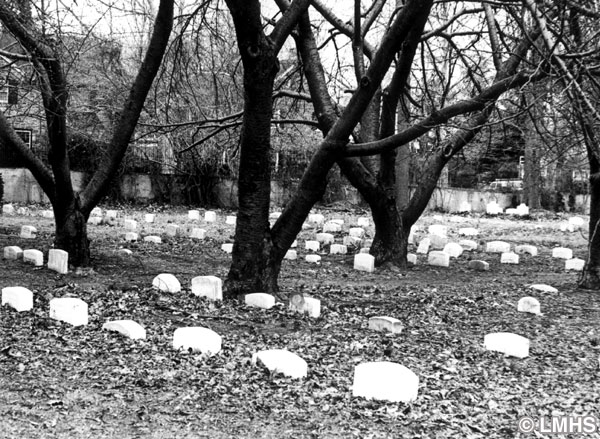

The burial yard was increased in size several times, and now is about 1-1/4 acres and known to contain more than 2100 bodies recorded, and possibly several hundred more never mentioned in writing. About 20% are children.

People died of alcoholism, apoplexy, accidents, bilious fever, burns, childbirth, cholera, consumption, diabetes, drowning, dysentery, freezing, kidney stones, heart attack, hives, lockjaw, murder, palsy, pneumonia, poison, smallpox, suicide, typhus, war wounds, an unidentifiable “white swelling” and yellow fever.

Most of the 246 gravestones still visible in the cemetery date from 1801 and 1804 when John Dickinson sold, for token amounts, two acres to the meeting to extend ground for burials and later, for other buildings. This was the famous John Dickinson, lawyer and statesman who never lived in Lower Merion but owned land here. He represented Pennsylvania in the Stamp Act Congress of 1765 and drafted its declaration of rights and grievances. He encouraged the populace by his Letters from A Farmer in Pennsylvania, to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies to protest harsh British taxation. Yet he did not sign the Declaration of Independence, for which he suffered disapproval, but later served in the patriot militia and most importantly helped draft the Constitution.

A researcher in the early 1900s found some 62 names of militiamen serving in the Revolution who she claimed are buried at Merion Meeting.

Now in the first years of its fourth century, the old “yard” next to the meetinghouse resembles nothing so much as a shady park with only a few standing grave markers (some illegible). Only ashes of Quaker family members may be buried now in Merion Meeting’s cemetery, where a peaceful quiet still comforts the bereaved.