The Lenape

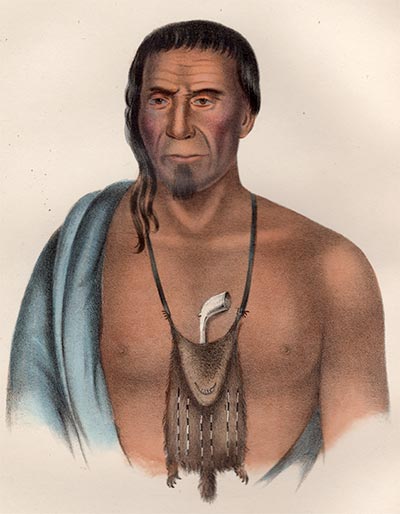

The ancestors of the Lenape had hunted in eastern regions of North America for thousands of years, adapting through time to the changes in climate and landscape. By 1,200 A.D. these small and highly mobile bands had developed new strategies that gave them more efficient use of the land and its resources. Within a few hundred years they had formed into the several nations who met the Europeans after 1500. One of these bands called themselves Lenape (len-AH-puh).

What today we know as the Delaware River takes its English name from Sir Thomas West, Lord de la Warr, the first governor of the Virginia colony. To the Lenape, this river and the land around it was called Makeriskhickon and, in many ways, this always flowing river was the lifeblood of these people. In their own terms these people called themselves Lenape, meaning “the people.”

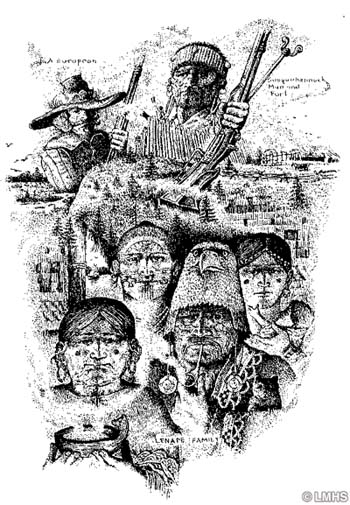

The Europeans first referred to all of the Lenape bands along the western side of Makeriskhickon, as well as to two other nations whose territories touched the “Delaware” River, by the collective designation of “River Indians.” All of these groups were later called “Delaware.” They spoke a variety of Algonkian tongues, now collectively called the “Delawarean” languages.

The Lenape Bands

At the time of the arrival of Europeans in the Middle Atlantic region, the Lenape people were organized into more than a dozen different bands, each with its own area for winter hunting, and its own summer station along the Delaware River. Most of the year was spent at these summer fishing stations. The individual band would “aggregate” into a social and economic unit for the warm months. Each individual family within the band would then “disperse” for winter hunting.

While these bands were somewhat flexible in membership, each tended to have a core group composed of closely related members. The young men in each band stayed within their birth band until they married, then would join the band of their wife.

The Lenape band living in the Lower Merion area was one of the largest of all. They traditionally summered in the rich swamps at the mouth of the Schuylkill, but hunted over the entire southwestern side of the Schuylkill River drainage which was their foraging territory.

Lenape Life

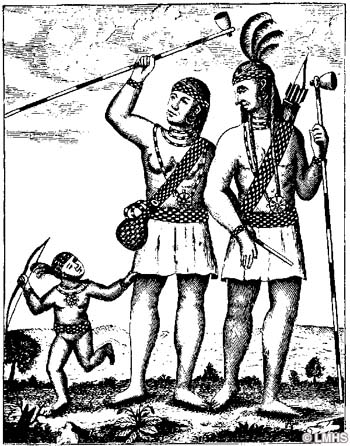

The Lenape living in the resource rich area of southeastern Pennsylvania developed a sophisticated foraging lifestyle during the Late Woodland period (c. 1100-1600 A.D.). They hunted and fished and gathered many different kinds of plants, such as goose-foot and wild millet, in order to feed themselves. In the fall, hickory nuts and acorns were gathered and processed for food. Among the animals collected by Lenape women for food were bird eggs, nestlings, frogs, turtles and shellfish.

During the summer, everyone helped fish for shad, sturgeon, striped bass, eel, shad and many other water-dwelling creatures, using complex woven traps, large nets and harpoons. Lenape men also hunted in the surrounding forests for deer, elk, bear and birds, using the bow with arrows tipped with flat, triangular stone heads…finely chipped and very sharp. Other foods that now sound less inviting, such as caterpillars, also were important to the Lenape.

The Lenape lived simply; each band was made up of several related families who worked and ate together. The members of any band could marry into any other band within the Lenape area, and rarely did they marry someone who was not a Lenape.

In 1985, excavations undertaken for the University Museum in Philadelphia located evidence of some small structures of the kind described by William Penn, who provided most of the direct descriptions of Lenape constructions:

“Their Houses are Mats, or Bark of Trees set on Poles, in the fashion of an English Barn, but out of the power of the Winds, for they are hardly higher than a man…”

New Prospects

The arrival of Europeans provided the Lenape with a new set of opportunities. Dutch traders from Fort Amsterdam, located on the North (Hudson) River, came down to what they called the South River in 1623 specifically to trade with the Susquehannock. Those people, the most powerful native nation in Pennsylvania, brought furs overland to the Delaware River to avoid the renewed conflicts between the Powhatan Confederacy and the English colonists on the Chesapeake River.

The Dutch put up a tiny trading post, Fort Nassau, on the Jersey side of the river opposite the mouth of a river they called the “Hidden Stream” (“schuylkil” in Dutch). The swamps and islands at the mouth of the Schuylkill made it difficult for early sailors to identify the true course of this river, so well-known and easily traveled by the Lenape.

The people of the South Schuylkill band became important figures in the quests of these various European traders for “legitimacy” as regards trading rights and land claims. Until the Swedes arrived in 1638 and bought land at Hopokehocking (now Wilmington) from the Brandywine band, the Schuylkil River people were the best known of the Lenape bands.

The Dutch came to “their” South River primarily to trade with the Susquehannock, but did not set up a permanent fort or individual homesteads. Before their Swedish competition arrived, there was little concern with land claims and territorial rights.

The Swedish colony was established principally to trade for furs, but failed to make a serious dent in the Dutch fur market. Taking a lesson from the Virginia Company, the Swedes went into the production of tobacco. The expansion of Swedish farmsteads and their continuing efforts to crack the Dutch fur monopoly, led to an interesting contention between the Swedes and the Dutch over land rights.

To counter the Swedish expansion into the Schuylkill Valley, the Dutch bought a few acres from the Lenape and built a small fort called “Bevers Rede” on the west banks of the Delaware. These deeds provide us with clues to the membership and territory controlled by the dominant Schuylkill River bands of Lenape.

Fur Trade

During the period following the Swedish entry into the South River (c. 1638-1660), the local Lenape had slight profits from the European competition for furs. The Lenape and their immediate neighbors had only the furs that they hunted from their own territories to trade; the Susquehannock were middlemen in the fur trade that extended out into the Mississippi Valley. Thus the Lenape were, as Swedish Governor Printz put it, “poor in furs.” These sales provided the Lenape with one means of access to highly valued trade items such as metal goods and blankets.

A second source of European goods derived from the sale of maize to the Swedes. The Lenape had always grown a bit of maize in their summer gardens, but after 1640 they increased the amount planted to sell to the Swedish colonists. The Swedes were concentrating their planting on tobacco for export, and bought maize from these Lenape foragers at lower costs than the value of tobacco. In this way the Lenape gained trade goods while not having to deal with the problem of food storage.

In addition, the Swedes provided a new and useful means by which the Lenape could make it through particularly bad winters. If the hunting was bad, Lenape families could rely on the Swedes for supplementary rations during the “starving time.”

Land Sales

Another Lenape technique for gaining access to European goods involved the sale of land. In general, the plots sold were small holdings and the goods received were considerable. Lands sold to one group could often be promised or “sold” to another group at a later date.

At a major gathering in 1654, six members of the North Schuylkill band were joined by two Lenape from the South Schuylkill band and two other Lenape from a third band. This gathering led to a major land sale. The North Schuylkill band sold a huge portion of the lower part of their territory, excepting “Passaijungh,” where they continued to spend the warm months doing their traditional fishing.

Penn’s Grant

The lands that became Pennsylvania came as a Crown grant to William Penn. Penn believed that the wholesale purchase of land from its native owners, and the subsequent division and resale of small plots, would make him fabulously wealthy. By the time Penn received his grant and developed his plans for what became “Pennsylvania,” thousands of English colonists already had come into the area.

This increase in population, most of whom purchased small tracts of land along the Delaware River, began to influence native fishing and foraging strategies by the 1660s. Rather than sustaining their summer fishing stations directly on the Delaware, individual Lenape bands began to shift their summer stations further up their respective streams. From c. 1660 to 1680 the Schuylkill River and other other bands were also relocating their summer stations further up river, with the South Schuylkill band shifting to a location in the Lower Merion area.

Penn’s Purchases

Between 1682 and 1701, Penn patiently negotiated the purchase of all of the holdings of every one of the Lenape bands, except those areas on which the individual bands “were seated” (had their summer stations). The first of these deeds were drawn up in July 1682 by William Markham, Penn’s agent, shortly before Penn himself arrived in the New World. The deed that is of most interest concerns the sale to Penn of all of the lands claimed by the South Schuylkill band (what is now Montgomery County).

The following July, two different Lenape bands came to negotiate sales of their lands to Penn for an incredibly rich array of trade goods. The first of these sales was made by the band living west of the Schuylkill. They sold all the land lying between “Manaiunk alias Schulkill” and Macopanackhan (Upland or Chester) Creek. This sale included land only up as far as the hill called Conshohockan.

These sales did little to change Lenape life ways other than to provide them with a vast quantity of useful goods. From the list of goods that Penn used to “buy” this tract, we can estimate the band size: 30 adults and possibly an equal number of children, since the goods involve items in multiples of 15. For the men, there are 15 guns, knives, axes, coats and shirts plus 30 bars of lead. For women, there are 15 small kettles, scissors and combs, but 16 pairs of stockings and blankets.

Westward Moves

- Archaic period spear head

- Full-grooved, pecked, cobblestone axe head, c.8000 BC to 4000 BC

- Sway-backed knife, c. 10,000 BC to 8000 BC

- Bannerstone/Atlatl weight, c.4000 BC to 1000 BC

- Jasper (a variety of quartz) point and scraper

- Knife point (handle added) c. 1000 BC to 1550 AD

- Pecked & polished chisel, c.8000 BC to 4000 BC

- Dart heads or knives

- Antler harpoon

- Gorget (soapstone) pictograph, c. 1000 BC to 700 AD

- Chopper/hoe blade c. 1000 BC to 700 AD

- Pitted stone, 8000 BC to 4000 BC

All of the Lenape bands continued to live in the Delaware Valley for another 50 years, but at locations further up the streams. They lived in much the same way that they had for centuries before…and continued to reside in these areas for another 50 years.

Only in the 1730s was the density of the English settlement and the subtle influences it had on native life-ways, considered a potential problem to the Lenape. Many were marrying or settling among the colonists and the traditional modes of living were becoming difficult to follow in the lower Delaware Valley.

Between 1733 and 1740, all of the conservative members of many Lenape bands had decided that economic opportunities and the chance to maintain the old ways lay in moving west. In leaving the coastal plain, these Lenape set the pattern that would be followed by early colonists and other immigrant groups to follow…moving west for opportunities that lay beyond the Atlantic shore.

Lenape had been moving west since at least 1661. When William Penn arrived, many Lenape already had left the Delaware Valley and others were ready to sell their lands and move out to central Pennsylvania and beyond. Most of the conservative and traditional Lenape people had left the Delaware Valley by 1740.

The numbers of Lenape who simply merged into the colonial society explains some “disappearances” of many aboriginal groups. For the Lenape, the attraction of wealth to be gained from the fur trade pulled many people west more forcefully than they were being pushed west by colonial population expansion. These Lenape people have joined with many other peoples to become the foundation for modern American society.