The Revolution Touches Lower Merion

In 1776, the capital city of the colonies was Philadelphia. In 1777, George Washington moved his army south from the Hudson River tracking British General Howe who had embarked his army to sail south and enter Chesapeake Bay where they landed at Elkton (then known as Head of Elk) and headed into Pennsylvania.

Washington and Howe and their two armies clashed at Brandywine Creek on September 11, 1777, and Washington’s men lost to the redcoats. The Americans retreated toward Philadelphia, crossed the Schuylkill, avoided the town, moved north, camped near Falls of Schuylkill and Indian Queen Lane for a day’s rest, then on to Roxborough/Manayunk.

The Continentals in Lower Merion

On Sunday, September 14, Washington’s army waded the Schuylkill at Levering’s Ford (near today’s Belmont/Green Lane bridge). Before dark they climbed the hill, followed Meeting House Lane, entered the road to Lancaster just behind Merion Friends’ Meetinghouse, turned right and deployed into open fields for the night.

Officers probably slept at the Buck Tavern (on Lancaster Avenue where Haverford and Bryn Mawr merge) about three miles ahead. Next day, September 15, General Washington at the Buck wrote a letter to Congress pleading for supplies. Help was not likely; congressmen were packing to flee west to Lancaster then to York where the Continental Congress would reside September 30 to June 27, 1778. Washington continued his march west partly to deflect the British from a supply depot at Reading.

Two Minor Battles, Then Came Germantown!

If reconstruction of events is correct, the British and Americans clashed in the first battle after Brandywine on September 16 outside of Lower Merion Township, near White Horse Tavern off Goshenville Road. It was the “Battle of the Clouds” when torrential rain wet ammunition and the patriots again bowed in defeat.

The next encounter in the same vicinity, known as the Paoli Massacre, occurred September 20. General Wayne and 1,500 men on a mission apart from the main army, met disaster, with many killed. Discouragement for Washington culminated on October 4 with the Battle of Germantown when autumn fog fouled plans, and the Americans lost again. Meanwhile, the British were happily ensconced in Philadelphia.

Lower Merion: No-Man’s Land

In such fine country as the Welsh Tract, lying as it did between two enemy armies during the War for Independence, its farmers did not escape the forced requirements of both the British and the Americans, each side helping itself freely to food for men and hay for horses.

Lower Merion became a no-man’s land that neither side controlled and was repeatedly raided by foraging parties. Some said the British were more welcome to the goods because they paid in cash, whereas the colonials paid only in notes or orders which were usually quite worthless.

It is true that the American forces were more demanding of the Quakers as several severe orders came from Valley Forge aimed at the farmers who wouldn’t fight and were accused of being Tories. These Welshmen were not people who went out and publicly defended or fought for a cause. In their quiet and dignified manner they favored the patriots, but the Society of Friends preached non-violence and the elders, at least, opposed any active part in the war.

Younger Quakers, however, were not so strict in their views. Many served in the Philadelphia County Militia (their Seventh Battalion was recruited in Upper and Lower Merion) and many young men gave up membership in the Society of Friends so they could fight against British tyranny.

Cornwallis vs. The Militia in Lower Merion

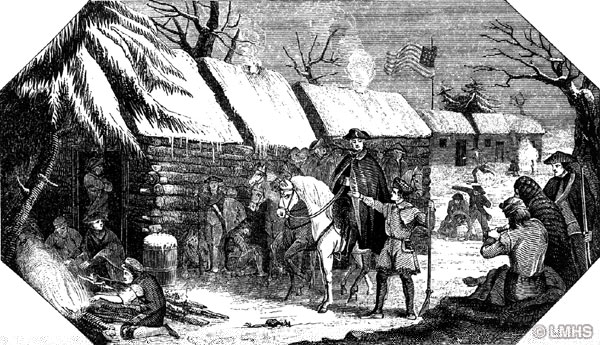

It was the search for “necessaries of life” that created the only other Revolutionary War episode in Lower Merion. While Washington’s men camped at Whitemarsh in November-December 1777 recuperating from losses in the Battle of Germantown, forage parties prowled on both sides of the Schuylkill for both armies. Pennsylvania militiamen were posted in Lower Merion to keep the enemy at bay.

The morning of December 11, 1777 Washington ordered his army to leave Whitemarsh and march down to Matson’s Ford (Conshohocken) to cross the river on a makeshift bridge of wagons to regroup in the Gulph (“hollow between hills”) and move thence to Valley Forge. Apparently by coincidence that same day, early in the morning, General Cornwallis and 1,500 (numbers vary) dragoons left Philadelphia on a foraging expedition into Lower Merion.

Following is a report by patriot General James Potter of what happened:

“Last Thursday, the enemy march out of the City with a desire to Furridge; but it was necessary to drive me out of the way; my advanced picquet fired on them at the Bridge; another party of one Hundred attacked them at the Black Hors [Black Horse Inn, Old Lancaster Road and City Avenue]. I was encamped at Charles Thomsons’ place [Harriton House] where I stacconed the Regiments who attacked with Viger. On the next hill I stacconed three Regiments, letting the first line know that when they were overpowered the[y] must retreat and form behind the second line, and in that manner we formed and Retreated for four miles; and on every Hill we disputed the matter with them. My people Behaved wel….”

But the day was conclusively lost when patriot General Sullivan, engaged in moving divisions across the makeshift bridge toward the Gulph, looked up at the hills (where his scouts had spotted redcoats chasing Potter’s men) and, uncertain of enemy numbers, decided to withdraw.

The infuriated Potter wrote:

“Had the valant Solovan covered my retreat with the two Devissions of the army he had in my rear, my men could have rallied, but he gave orders for them to retreat and join the army who were on the other side of the Schuylkill…about a mile and a half from me…[this left the enemy to] plunder the Country, which they have done without parsiality or favour to any, leave none of Nesscereys of life Behind them that they conveniantly could carry or destroy.”

Of the episode, Washington wrote “…we…intended to pass the Schuylkill at Madisons [Matson’s] Ford where a bridge has been laid across the river.” But based on “best accounts we have…4,000 men under Lord Cornwallis, possessing themselves of the heights of the road leading from the River and the defile called the Gulph…” it was deemed too great a risk to proceed.

Instead, Washington directed his army, 11,000 men, to cross the river farther upstream at Swedes Ford (Norristown), and march back to Gulph Mills. By the time they arrived, the British marauders had vanished back to the balls and dinners of Philadelphia.

Tradition says that Cornwallis returned along Gulph Road as far as Harriton, then found his way to Haverford Road and spent the night at Pont Reading, house of the Humphrey family. Meanwhile, Washington and his men bivouacked in the hollow of the Gulph from December 13 to 19, 1777, and from there marched to Valley Forge.