Old Roads and Travel

From 1750 to 1840, the roads heading out of Philadelphia, especially the western routes, were the main pathways of commerce and frontier expansion in the colonies and early republic. Pennsylvania was one of the most important gateways to the west, with the rush really beginning after the French and Indian Wars. The Delaware Valley and south central Pennsylvania were also the gateways to the Shenandoah and Blue Ridge regions of the south. It is no wonder then that historians writing in the early twentieth century remarked that the Main Line possessed the greatest number of “colonial relics” of any of the former colonies. The typical colonial roads were narrow two lane affairs that followed old Indian trails that previously followed animal paths.

Lancaster Turnpike: Early History

The first roads followed ridgelines where drainage was good, or watercourses where grades were more even. Nonetheless, they were muddy and dangerous in bad weather.

The Lancaster Turnpike was revolutionary when it opened in 1794 for both its width and surface. The 24-foot wide right of way was Macadamized, covered with densely packed fine gravel laid over a deep foundation of coarser stone. Just as with highways today, there were load restrictions meant to protect the pavement. Wagon wheels had to be a certain width, and heavy loads were not permitted at all in the winter when the surface was more fragile.

Many contemporary drivers curse the convoluted routes of roads such as Conshohocken State Road, or Conestoga Road, or deplore the traffic on Lancaster Avenue. These were also the most important east-west routes of the 18th and 19th centuries, for both people and freight.

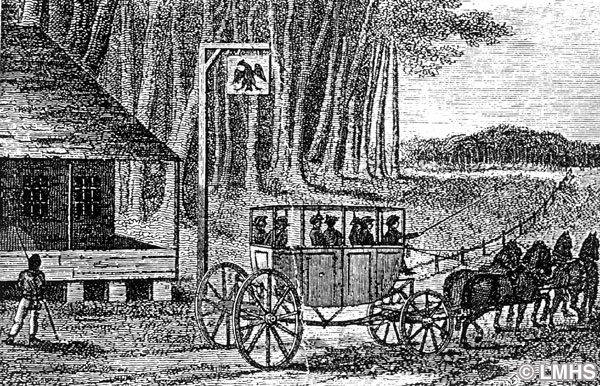

Stage Coach Travel

A stagecoach was a carriage, drawn by four or six horses, used to carry passengers and mail on a regular route. The first stage lines were established in colonial America in the mid 1700s, based on a London system started 80 years before. They operated chiefly between Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

The coaches bounced along at a brisk ten miles an hour, lucky to make 30 or 40 miles a day, weather permitting. Horses were changed at relay stations every 15 or 20 miles.

In 1818, a stage line ran through Merion from Chestnut and 6th Streets in Philadelphia. It passed through Merion, Gulph Mills, King of Prussia, Valley Forge and Phoenix Iron Works to French Creek Boarding School…one day’s trip. The stage ran, outbound, on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday and returned to Philadelphia on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. The fare was $1.75…or 6 cents a mile.

The fast stages imposed great stresses upon the narrow, rutted roads, as there were schedules to be maintained and prestige for cutting time off a run. Different stages also raced between stops, to be the first to arrive at a wayside inn.

There was a hierarchy of the establishments: the inns served the stage traffic and other places served the drovers of the mammoth Conestoga wagons. Innkeepers jealously guarded their reputations, since losing the patronage of one of the stage lines could lead to ruin in the competitive marketplace.

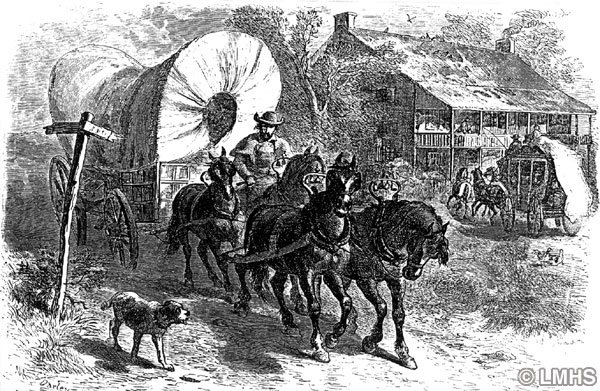

Conestoga Wagons

A Conestoga wagon was a sturdy, colorful covered wagon named for the Lancaster county town where it was first built. 25 feet long, its canvas top supported by huge hoops 11 feet high, the vehicle weighed over 3,000 pounds. The massive wagons were made of white oak and poplar with a sag in the middle to take the strain off the ends. Sturdy iron wheels and axles were needed for the rough roads to be traveled and the streams to be crossed.

A wagon cost $250, but the six powerful horses that drew it were worth $1,000. Each horse sported colored headbands and ribbons and a set of varitoned bells which heralded the rumbling approach of the Conestoga.

It is not difficult to imagine the strain of pulling heavy loads up and down the numerous hills of the area. Many teams had at least one lame or sick animal, and the casualties along the road were many. Furthermore, the cost for stabling a horse overnight was the same as lodging for a person, so it was not uncommon for the teams to be left out in all kinds of weather.

Wagonmasters were a tough, hard-bitten, resourceful class of men: seasoned by weather and experience, ready to fight for a load, not hesitant to force another wagon off the road in a right-of-way dispute. Unlike the more stylish stagecoach drivers, these men wore rough homespun and leather and a flat wide-brimmed hat to give some protection from sun and rain. Pockets would bulge with cheap cigars called “stogies,” presumably a corruption of Conestoga. This rough era came to an end when steam locomotives ushered in a new age of progress.