The Papermakers

Conrad Scheetz

The earliest Lower Merion mill noted on a map is labeled the “Schultz Mill,” which appears on the 1750 Scull and Heap Plan of the City and Environs of Philadelphia. The location northwest of Merion Meeting verifies this mill as that of the Schütz family, Protestant papermakers who settled in Germantown from Crefeld, Germany in 1733. Their name eventually became anglicized to Scheetz.

In 1748 Conrad Scheetz purchased from a Donald Davis 100 acres with an existing fulling mill (such mills processed woven or knitted woolen into a tight fabric) on Mill Creek. The site is now along Dove Lake Road, but neither the road nor the lake existed at that time.

Scheetz converted the mill to a paper mill known as the Upper Mill. His accounts with Benjamin Franklin show the purchase of rags for paper production and the sale of many types of paper to Franklin for his press. Some were personalized with watermarks bearing Franklin’s initials and symbols rather than those of the Scheetz mill.

By 1768, Scheetz had constructed a second mill downstream where a lesser quality paper was produced. It stood on the west side of the creek adjoined by a residence below where Old Gulph Road fords the stream in the vicinity of the 10 mile marker. This mill became known as the Lower Mill and it remained in the family until the end of the 19th century.

Scheetz had eight children who worked or married within the papermaking trade. Their family residence (redesigned during the Colonial Revival period), a spring house, and stone portions of a much altered barn are all that remain of the Upper Scheetz Mill today.

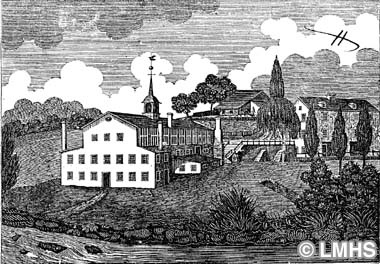

Dove Mill

The Scheetz Upper Mill took on new acclaim in 1798 when it was sold to Thomas Amies from Switzerland. He brought the name Dove Mill and the watermark of a dove to this site. Amies’ deed for the purchase of the Scheetz Mill identifies him as a cordwainer or shoemaker from Philadelphia.

Amies’ papermaking skills were presumably learned in his homeland (the Swiss produced some of the highest quality paper in Europe), and then furthered in America by a tenure at the Wilcox Ivy Mill in Chester. The watermark of a dove with an olive branch in its beak may have been derived from that mill, but for Amies it was intended to exemplify paper that could not be counterfeited.

The manufactory census of 1820 provides critical statistics on Amies’ business. He employed 12 men, 18 women, and 4 boys costing annual wages of $5,000. The fine paper produced annually had a value of $19,000. His mill investment reached $25,000 with paper stock valued at $12,000. Despite these figures that imply success, twice before Amies died (in 1849) bankruptcy was declared at his mill. Importation and industrialized papermaking processes gradually put Mill Creek’s handmade papermakers out of business.

Bicking’s Mill

Another German papermaker who settled in Lower Merion and established not just a paper mill but also a saw mill, a fishery on the Schuylkill, and a family cemetery was John Frederick Bicking of Winterburg, Germany. His original purchase in 1762 of a mill site upstream from the extant Barker’s Mill rapidly expanded to 255 acres, and reached the Schuylkill by 1798.

At that time he was taxed for a 40 by 50 foot mill, a 23 by 60 foot barn, a one story 24 by 30 foot stone house, a spring house, two log houses, and a cart house on pillars.

During the Revolution Bicking co-authored a petition labeled “Memorial of the Paper Makers of Philadelphia” sent to the Committee of Safety for Pennsylvania, explaining that if every man from 16 to 50 was conscripted to fill military ranks, all the paper mills on the continent would be shut down and no paper for printing offices or ammunition would be produced. The papermakers’ appeal for exemption was honored and papermakers were even called home from military service.

Bicking died in 1809 at the age of 79, and he and his family are buried in their cemetery that remains in a backyard on Fairview Road. His son David took over the mill, which prospered until his death in 1832.

Deringer’s Mill

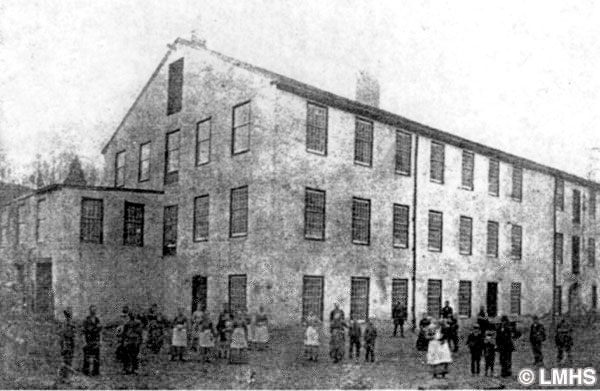

The next notable owner of the Bicking Mill was Henry Deringer, pistol manufacturer from Northern Liberties, who purchased the site in 1840. By that time a “tenement” for workers’ families is listed on the deed. The largest roofless structure that stands now in Rolling Hill Park (back from the creek) was apparently this building.

Little evidence exists to indicate considerable manufacturing of Deringer weapons was carried out at this mill. The site may have been an investment opportunity, for in 1849 Deringer sold it to his son-in-law, William H. Todd, a Kentucky planter for $7,444.50 plus an annuity to the widow of a former owner.

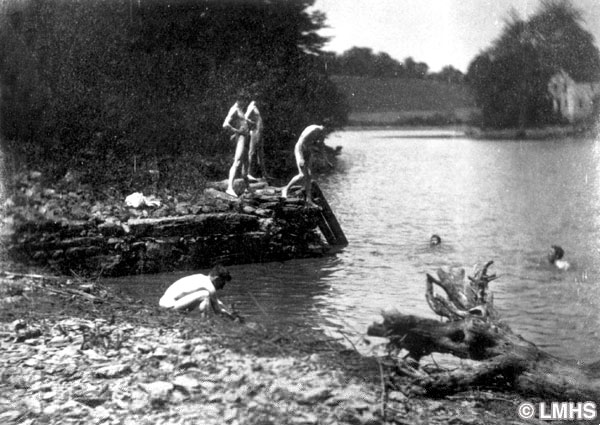

The value of the real estate was more accurately defined by the 1850 Census, appraising the mill at $50,000. Todd at the time was 44 years old, his wife Amanda 28, and they had an eleven year old son and three daughters under seven. They converted the paper mill to a cotton yarn manufactory with additional structures added to the site. The number of workers involved became so numerous that the community was called Toddstown. Nearly thirty years later, in 1878, litigation for debts forced Todd to sell his mill at a sheriff’s sale. The next owner, Gilbert Fox, carried on the business successfully under the name Glencairn Mill.

Walover’s Mill

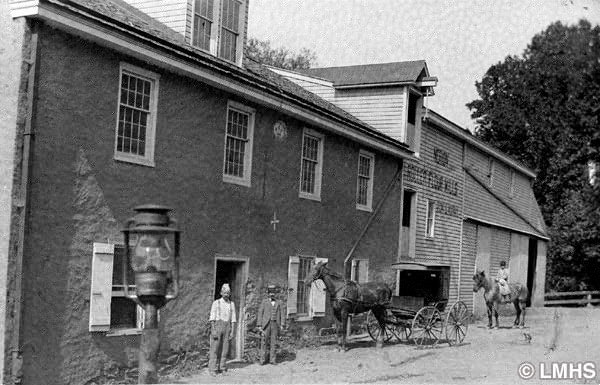

After the Revolution Peter Walover, an immigrant from Menz, Germany, settled in Lower Merion. He was trained in papermaking in America at the Paul Jones Mill in Manayunk after serving as an indentured servant to Henry Drinker. The mill and miller’s house he purchased in 1807 was one of John Roberts’ original paper mills. The buildings were located at the current hairpin turn in Mill Creek Road at the narrow bridge.

For nearly ten years Walover apparently ran an efficient and immaculate mill, but the economic recession that occurred after the War of 1812 forced him into debt. His 33 acres of land with three “messuages” and a paper mill were sold at a sheriff’s sale in 1818. These buildings remain today serving as suburban residences.

The millers’ early 18th century home is known as “Tayr Pont” and is characterized by a second story porch. The mill building itself, along the side of the road, was run as a paper mill until 1848 by the new owners, Horatius G. Jones and Evan Jones. At that time Evan Jones renovated it to a cotton and woolen mill. Later he converted it to a flour mill called Merion Flour Mills. A date stone stating “E J 1848 Remodelled by Edw. S. Murray 1890” indicates a later conversion by Edward Murray, whose business was known as the Merion Roller Flour Mills.

Mill Creek

became the locus for mills established by many other papermakers, but unfortunately remnants of these buildings are hard to find today. Family names that were prominent throughout the 18th and 19th century were William Hagy, another Swiss papermaker, John Robeson, whose family owned both paper and saw mills, and John Righter whose paper mills were located along Righter’s Ford Road. Of these three manufacturers, the Righter mills were the least enduring. The Hagy mill site was eventually converted to the Chadwick textile mill, which prospered until the end of the 19th century. The Robeson mill also was converted to textile manufacturing, producing materials into this century. Levi Morris founded the Harriton Flour Mill on Old Gulph Road below Pyle’s Dam and Morris Road in Bryn Mawr during the late 19th century. Some buildings converted to residences and a wheel house still remain.