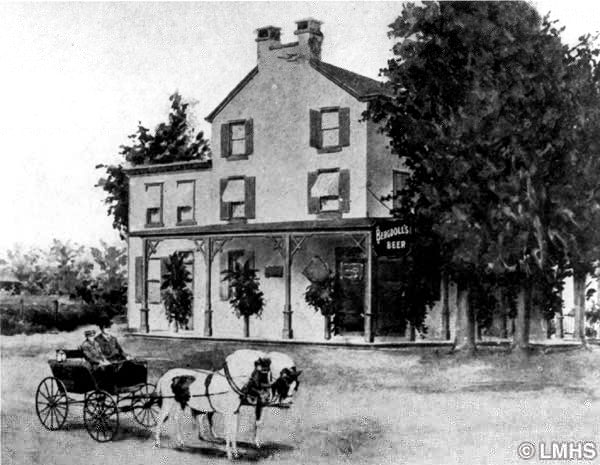

Taverns and Inns

Taverns and inns served many purposes other than as bars and hotels. A farmer did not have to be able to read. He could recognize a Red Lion, George Washington, William Penn, a Spread Eagle, the Turk’s Head…painted on the sign outside. They were like street signs and information booths for visitors seeking directions to relatives or locations of houses, farms, blacksmiths, lumber yards. Most patrons were male. Taverns were the living rooms for most neighbors because houses were small, ill-heated, crowded with children, and bereft of extra food and drink. A host would naturally entertain his cronies at the local tavern. Courtesies were exchanged in the form of drinks, and deals sealed by beverage. The taverns also served as spaces for serious business: voting place, post office, general store.

The Drovers

There were many kinds of taverns. Drovers of cattle had favorites, which had pasture land behind, or nearby, to accommodate huge numbers of animals with water and fodder available…enough to keep up the weight of every animal destined for stockyards in Philadelphia. These were the “long roaders” and the Red Lion in Athensville (Ardmore) was especially favored with its original 30 acres.

When the animals were gathered in for the night, wagonloads of hay moved through the herd with a man pitching fodder right and left; water troughs were kept full. Fortunately, properties surrounding such lots were spacious, houses scattered, and the owners not too fussy about smells. If you made the trip to town behind either a drove of cattle or a 100-mule packtrain, yours was not a journey in a rose garden.

The “Ordinary”

Well before the Revolution, the “Ordinary” supplied a menu at a fixed price, as well as a warming drink. Some catered to a better class of customer than the “long roaders.” In many cases, a blacksmith and wheelwright opened shop close by. The Conestoga wagons would pull into a tavern (or “stand”) for the night. Drivers would have dinner and companionship for awhile, but in good weather, to avoid room rent, retire to sleep in their wagons. Joseph Price, diarist, in his short tavern-keeping career, deplored this custom.

Further west, beyond Lower Merion Township, is the famous King of Prussia Inn and its distinctive sign, reputed to have been painted by Gilbert Stuart. British spies were known to congregate there seeking information about the troops at Valley Forge. Swallowed up between bustling highways, the inn’s demolition was halted by action of an historical society in 1953, and moved to a nearby location.

65 Choices

There were “tap” houses run by Irishmen beginning in the 19th century. These catered to farmhands, immigrants, and roustabouts. A slug of “red-eye” with a seegar (cigar) thrown in, cost three cents, wrote Josiah Pearce of Ardmore. Between Philadelphia and Lancaster, 61 miles, there were 65 taverns. “The traveller never was faced with a horrible death by thirst” (Josiah again).

Houses of refreshment along the Schuylkill’s canal catered especially to the muleteers responsible for driving mules to pull canal boats. Brawls, murders, and intense domino games characterized some of the river taverns. Wagoneers also participated. They traveled in from farms, used Ridge Pike, then came down to cross the Schuylkill and go into Philadelphia via River Road.

Some confusion as to names of these taverns results from the innkeepers moving from place to place, carrying the tavern signs with them: Robin Hood and Samson and Delilah, for instance.