“Freedom at Last!”: The Harrowing Wartime Story of Lower Merion’s Mariano Barone

By Simon Bank, Guest Blogger

Originally from Los Angeles, Simon is a sophomore at Haverford College studying history and philosophy. He currently works in the Quaker and Special Collection at Haverford College and has a passion for historical storytelling and archival research.

“This looks like it……yes, freedom at last!” wrote Mariano Barone, a Lower Merion resident, after his liberation from the German prisoner-of-war (POW) camp Stalag IIB (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley May 23rd, 1945). This was the second POW camp that Barone spent time in during the war and this liberation finally marked the beginning of the end of what had been a tumultuous and harrowing wartime ordeal. During the war Barone faced many challenges, “he was wounded in combat against the Vichy French in Algeria and twice was captured and held prisoner, in Italy and then Germany.” His courageous service earned him “several medals, including the Bronze Star, Purple Heart and Presidential Unit Citation” (The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 6, 1999).

Barone recounted some of his fascinating wartime experiences in letters to Russell Byerley, a shop teacher and coach at Lower Merion High School (LMHS) for over 20 years, who was determined to stay in touch with students involved with the war. Throughout the war Byerley amassed over 2,000 letters and photographs from 1,392 different individuals, most of whom were LMHS alumni, now held at the Lower Merion Historical Society. Byerley then compiled newsletters out of the correspondences he received and circulated them to hundreds of servicemen around the world in an effort to keep them connected to the Lower Merion community.

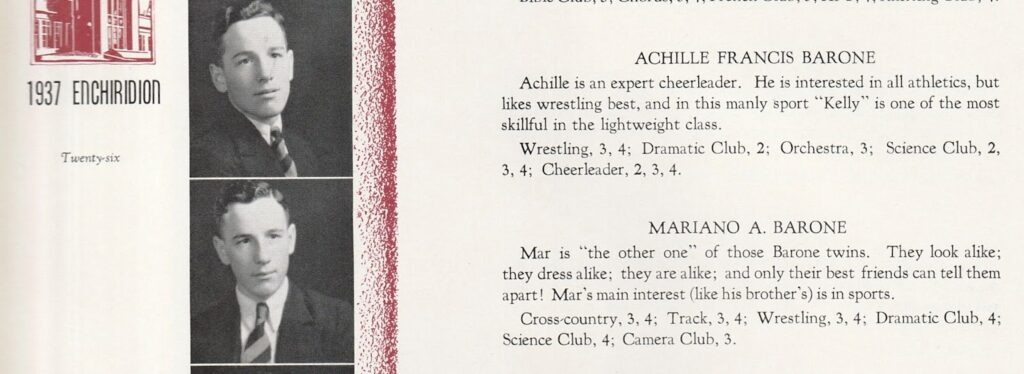

Through his communications with Byerley, Barone was able to remain in consistent contact with his friends and family back home. Barone’s father, Antonio, and his mother, Amelia, remained in their family home located at 722 Railroad Avenue in Bryn Mawr for the duration of the war. Both of Barone’s parents were born in Italy. They both immigrated to the United States in 1902 and settled in Manhattan. In New York, Antonio spent some time working in construction before eventually marrying Amelia in 1909. The couple quickly started a family which eventually grew to include eight children including Mariano and his twin brother Achille. The young family moved to Lower Merion sometime in the 1920s and Antonio began work as a gardener while his young children attended school in Lower Merion.

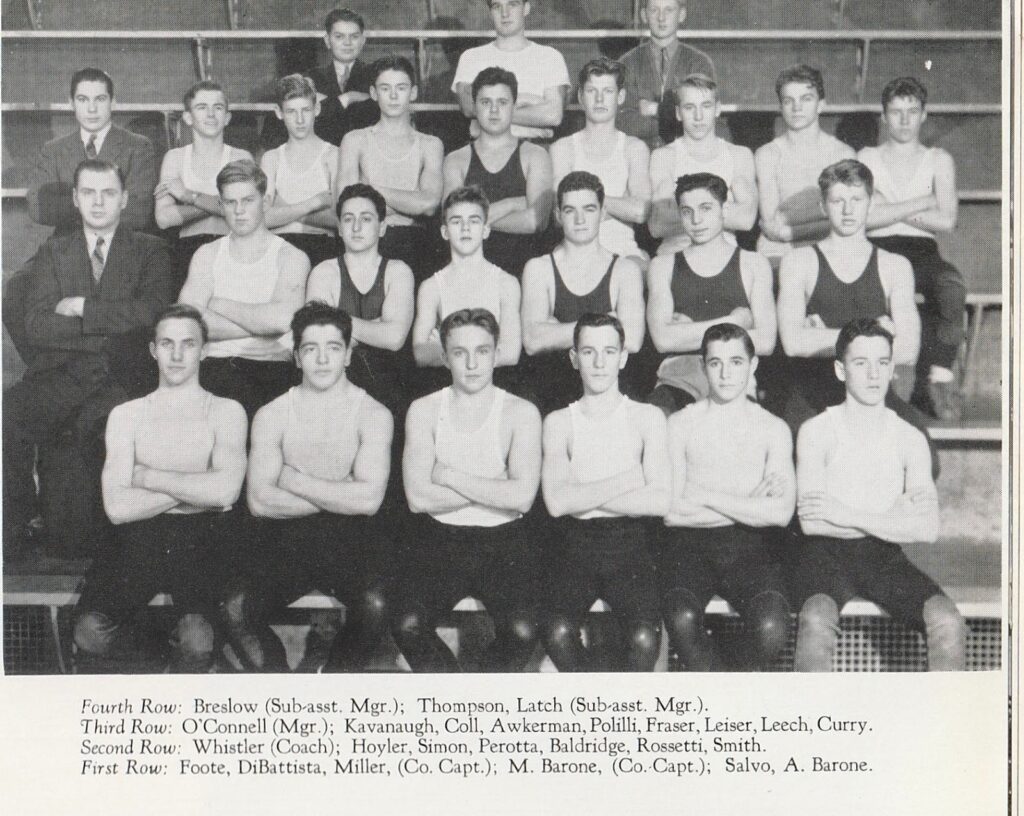

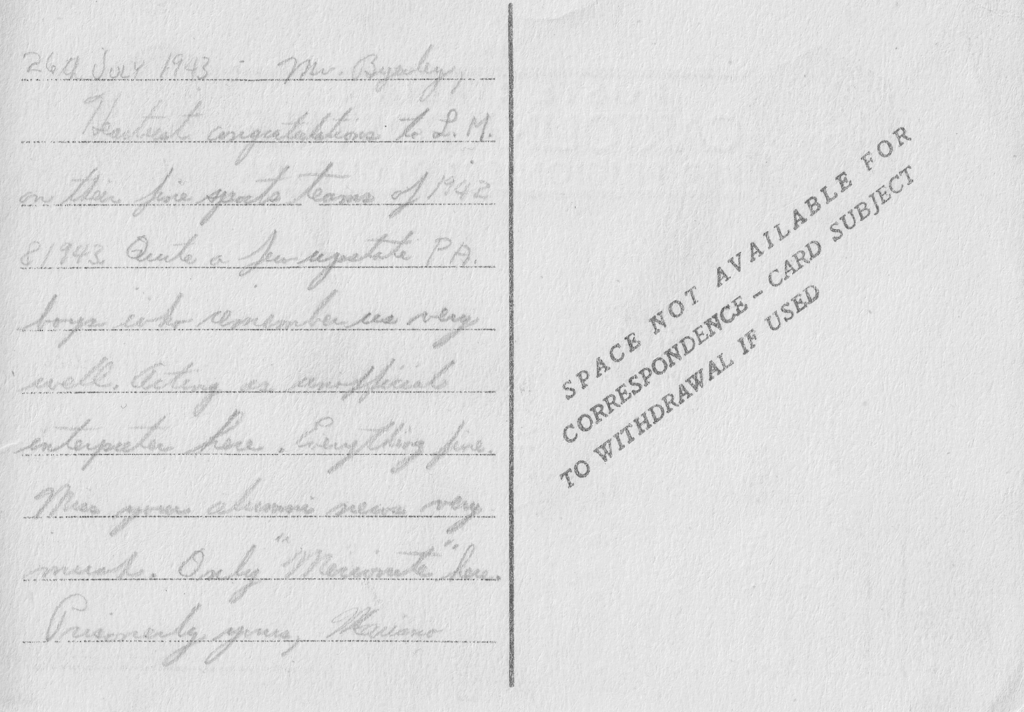

In many of his letters Barone offered his “regards to all the Merionites,” reflecting his connection and fondness for the Lower Merion community and Lower Merion High School specifically. In his time at Lower Merion High School Barone certainly made an impact on the community. As a member of the class of 1937, he lettered in cross country and wrestling (in the yearbook image below, Barone is bottom row, third from right) and was also a member of the track team. Besides his athletic pursuits, according to his high school yearbook, Barone was an active member of the Dramatic Club, Science Club and the Camera Club. Even while imprisoned Barone continued to think about LMHS, writing that he wished to give his “hardiest [sic] congratulations to L.M. on their fine sports teams” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley July 26, 1943).

Alongside Barone throughout high school was his twin brother Achille. In their high school yearbook their classmates described how they “they look alike; they dress alike” and “they are alike.”

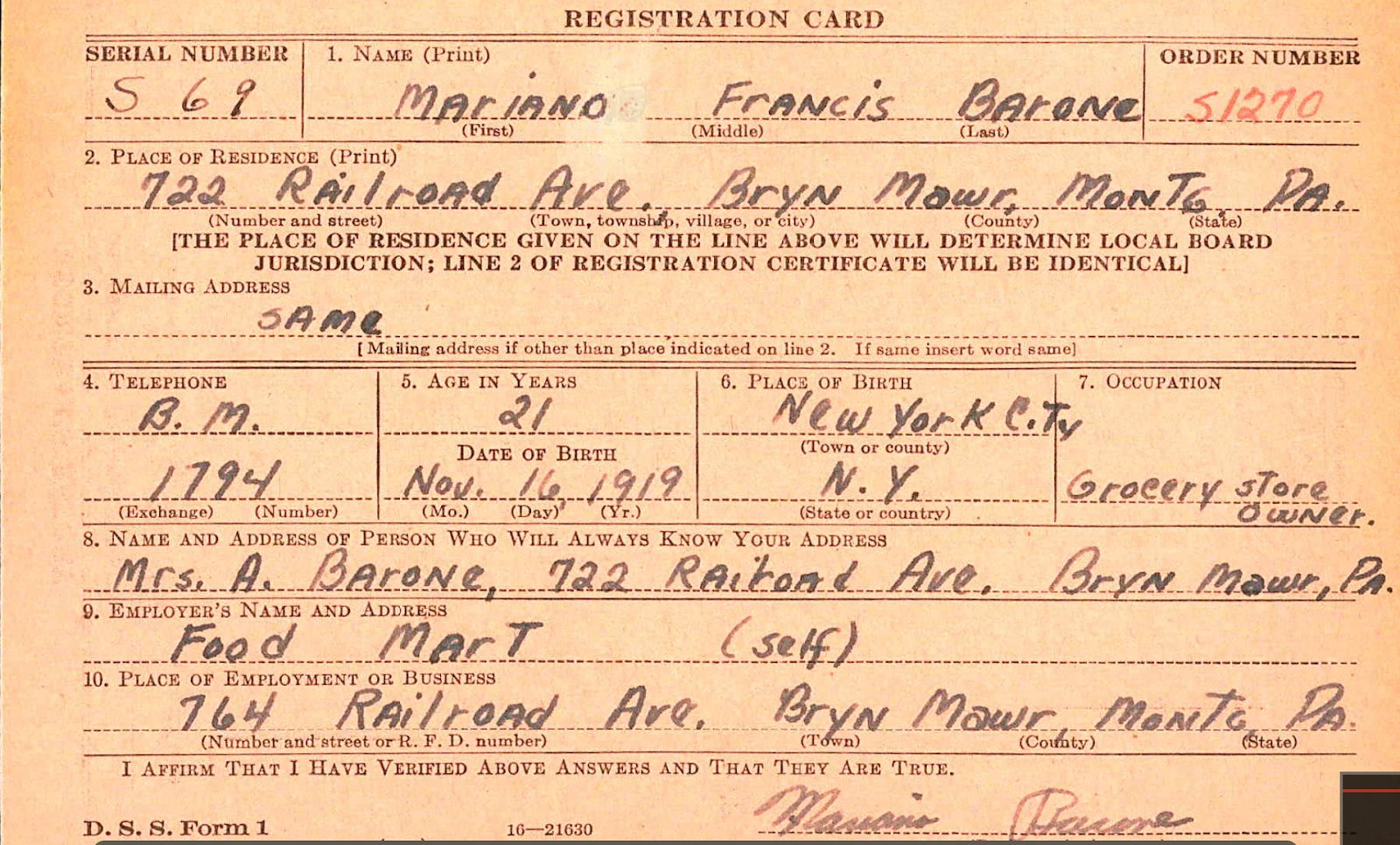

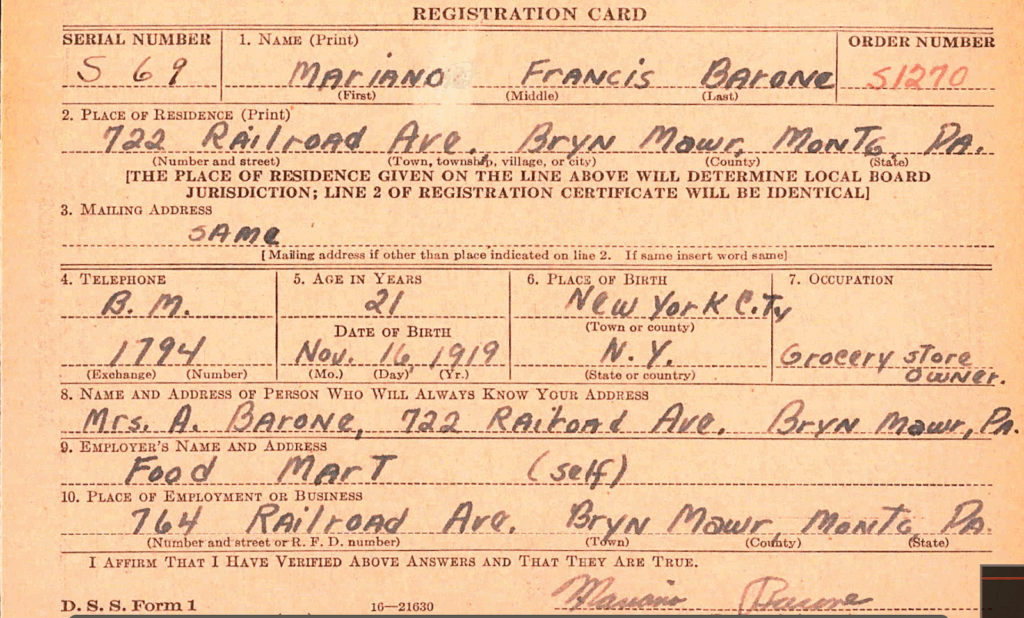

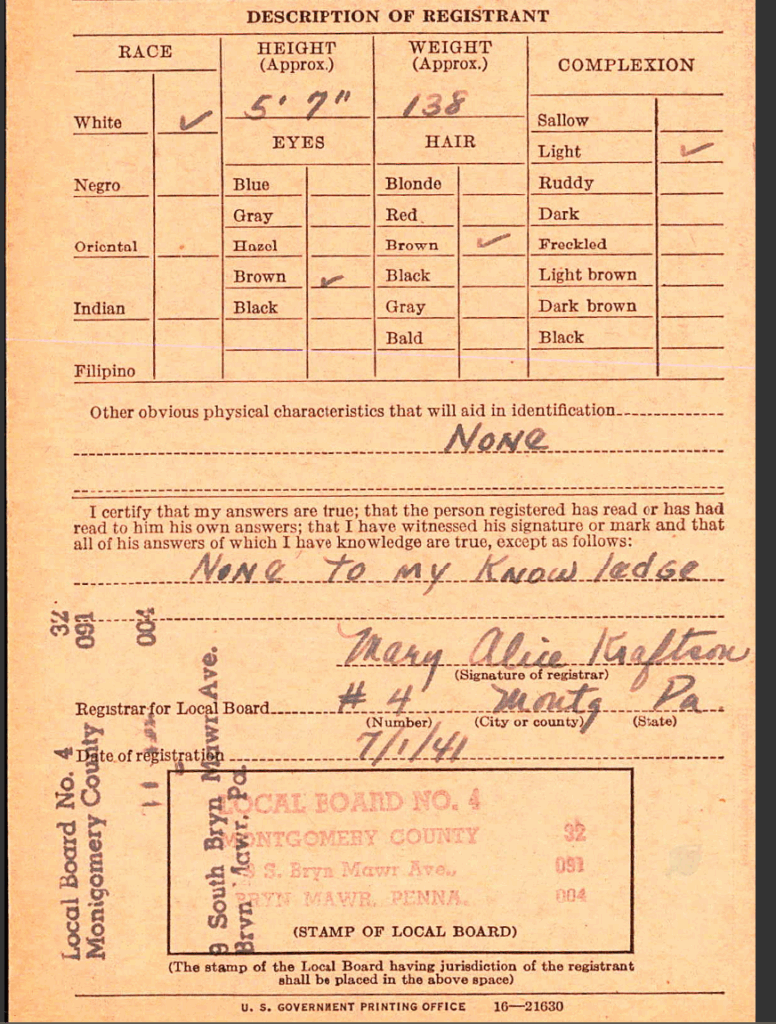

Following his high school graduation Barone began work alongside his brother. The two started a small grocery store (or “food mart”) where they served their community. This business was short-lived, however, as tensions began to grow in Europe. The two brothers were soon forced to register for the draft and a mere two years later Mariano Barone found himself stationed in Europe.

Barone was first stationed in the United Kingdom, specifically in the countryside which he described as “beautiful” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley September 16th, 1942). He was also able to visit “London…twice” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley September 16th, 1942). In his time in the United Kingdom, Barone was not directly involved with conflict; instead he focused his attention on “romance.” In one instance Barone comedically noted that courting British women was “just like boiling ice – a lot [of] water at first” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley September 16th, 1942).

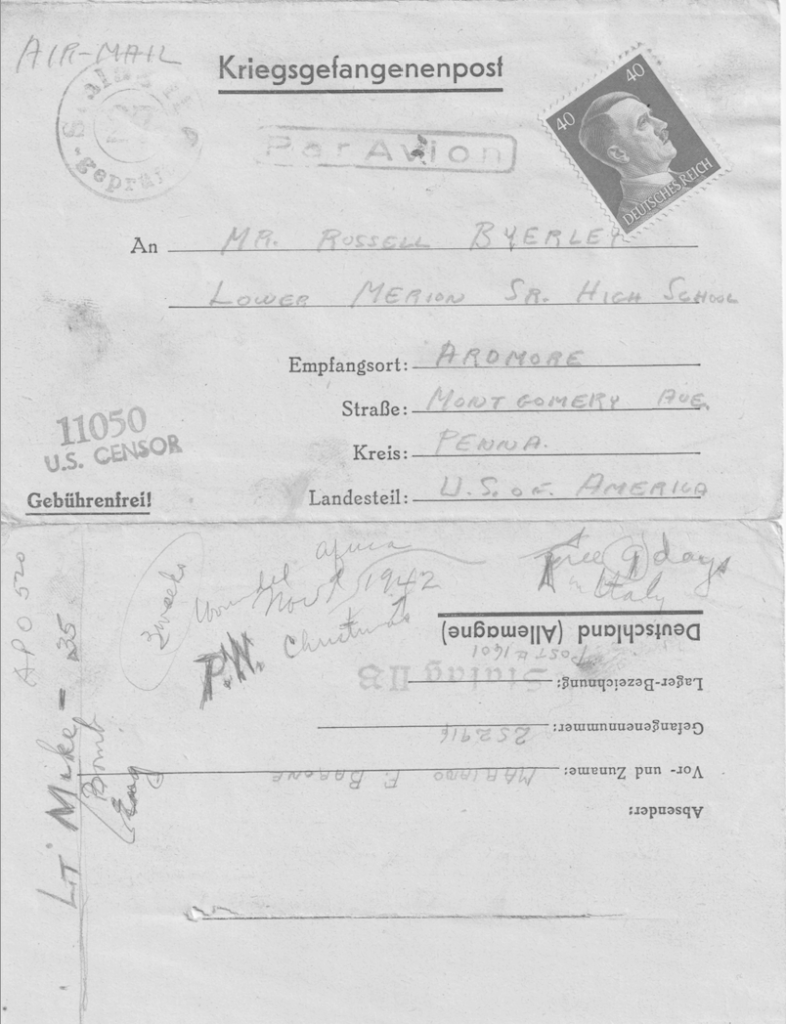

After multiple months spent in the United Kingdom, Barone participated in Operation Torch in November of 1942. Barone was injured in combat, however this was only the beginning of his struggles during the war. A mere eight months after Operation Torch, Barone was captured and imprisoned in the Italian POW Camp (or Campo) 59 located in Servigliano, Italy. While imprisoned in Campo 59, Barone continued to correspond with Byerley. He wrote that despite his situation, “everything [was] fine” besides the fact that he was lonely considering he was the “only ‘Merionite’” at the camp (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley July 26th, 1943). Despite this, however he remained in good spirits and even continued to demonstrate his sense of humor, signing off a letter to Byerley with the phrase “prisonely yours” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley July 26th, 1943).

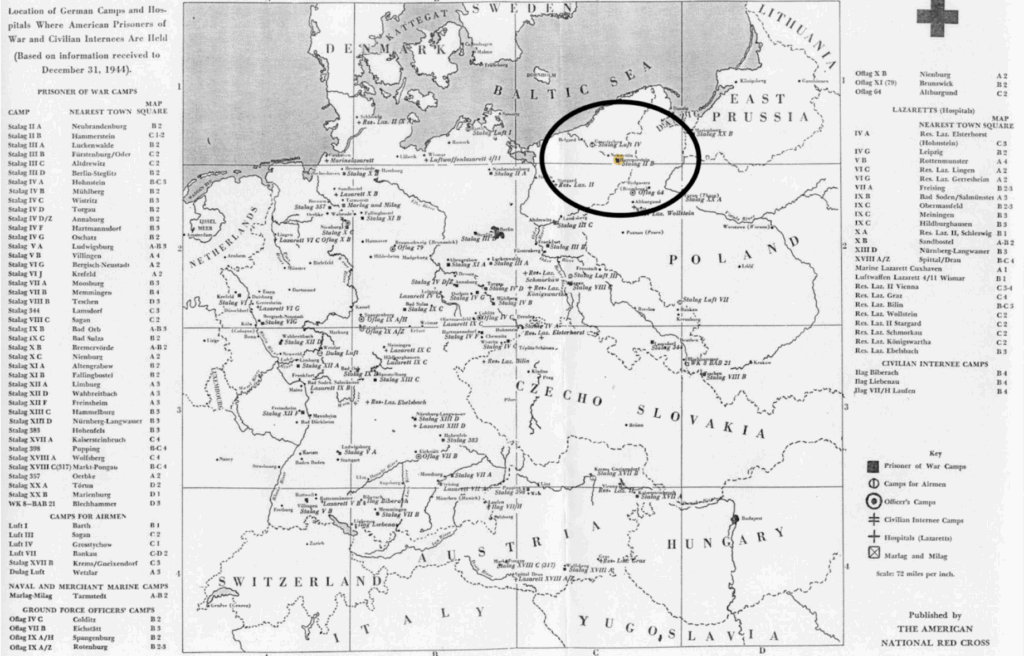

Barone was uniquely positioned in his time at the camp. As a first generation American born to Italian immigrant parents, Barone spoke Italian and thus, according to his letter, acted “as unofficial interpreter” while held at Campo 59 (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley July 26th, 1943). While life in Campo 59 wasn’t overwhelmingly terrible for Mariano Barone, his time at the camp didn’t last long. Following the Armistice of Cassibile in the fall of 1943, numerous logistical issues began to arise. One of these issues was the multitude of POWs held by Italy. The Nazis, who still controlled many POW camps, began to transfer a number of prisoners to their own camps. While it is unclear what exactly happened to Barone, it is clear that by December of 1943 he was imprisoned in the German POW camp Stalag IIB located in Hammerstein.

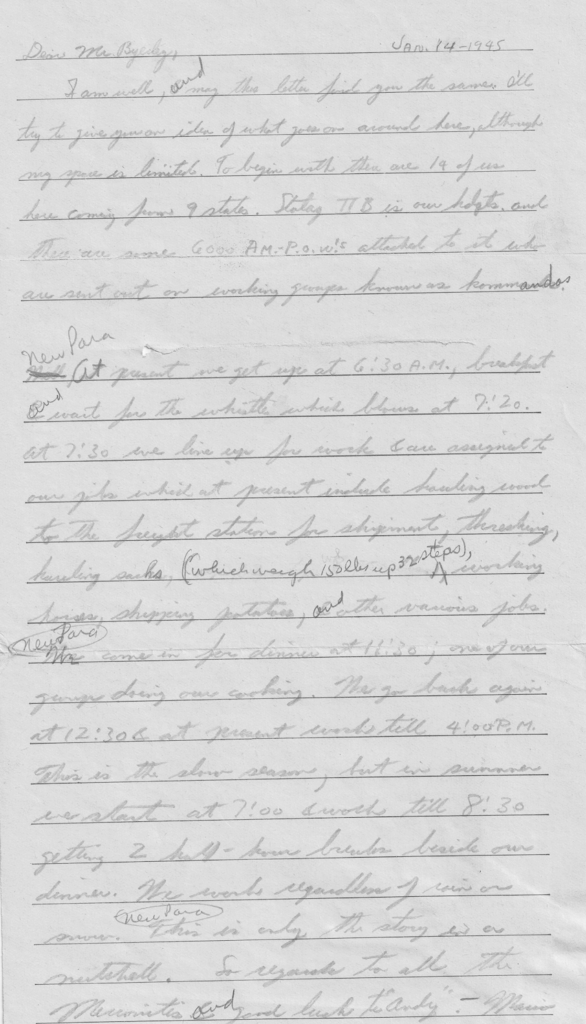

Barone attempted to provide Byerley with “an idea of what goes on around” the camp. He reported that there were “some 6000 AM.-POW’s attached to it who are sent out on working groups known as kommandos” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley January 14th, 1945). In his own kommando Barone wrote that there were 14 soldiers “coming from 9 states” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley January 14th, 1945). Barone explained how each morning the prisoners would wake up at 6:30, eat breakfast, and subsequently “line up for work” at 7:30 (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley January 14th, 1945). The prisoners would then be assigned their jobs for the day which varied and included “hauling wood to the freight station for shipment, threshing, hauling sacks (which weigh 150 lbs up 32 steps), working horses” and “shipping potatoes” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley January 14th, 1945). The prisoners would receive a break for lunch before continuing work for the remainder of the day. According to Barone, the prisoners would “work regardless of rain or snow” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley January 14th, 1945).

imprisoned in Stalag IIB.

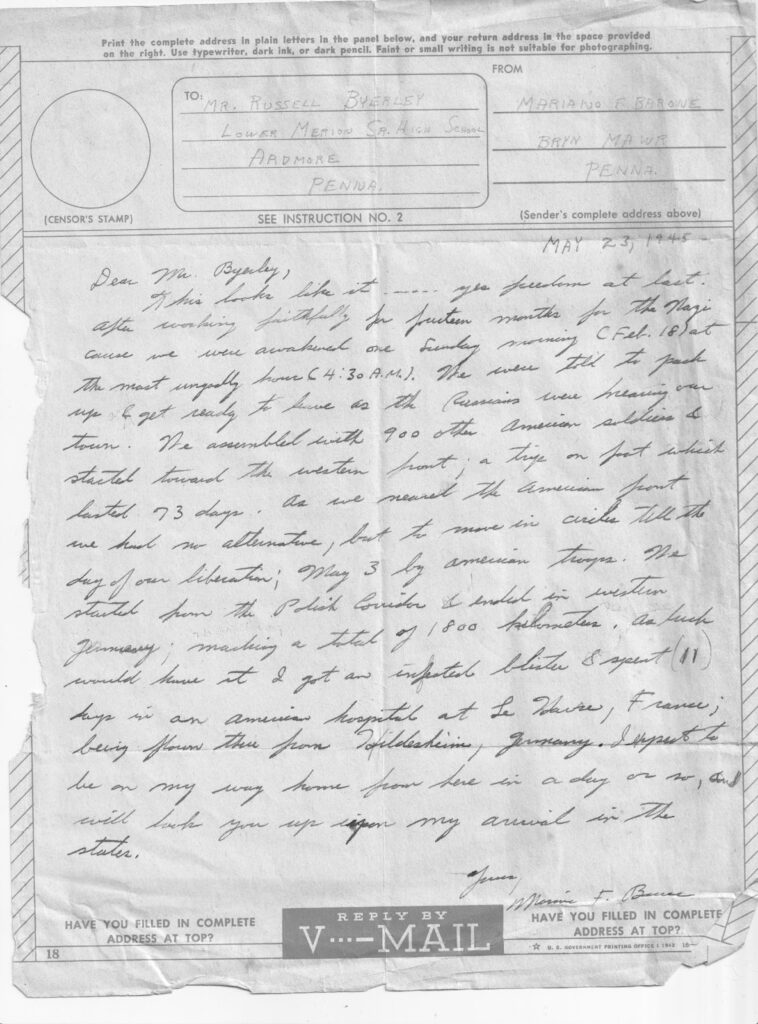

Barone would endure the harrowing conditions reported in his letter for around another month before finally being liberated on February 18th, 1945. He wrote that after “working faithfully for fourteen months for the Nazi cause” he had been awoken and instructed “to pack up and get ready to leave as the Russians were nearing our town” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley May 23rd, 1945). He then explained that he gathered “with 900 other American soldiers and started toward the Western Front,” on foot, which would take around 73 days (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley May 23rd, 1945). The group of freed prisoners finally reached allied controlled territory and were forced “to move in circle till…May 3” when they were finally liberated “by American troops” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley May 23rd, 1945). The prisoners’ journey from Stalag IIB to the time of their ultimate liberation was “a total of 1800 kilometers” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley May 23rd, 1945).

recovering in Le Havre, France.

While Barone was finally free, his struggles were not quite over. During the tumultuous journey Barone “got an infected blister and spent 11 days in an American hospital at Le Havre, France” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley May 23rd, 1945). Barone recounted his journey while recovering in the hospital and reassured Byerley that he expected “to be on [his] way home…in a day or so” (Mariano Barone to Russell Byerley May 23rd, 1945).

After finally returning home in the summer of 1945, Barone began to reintegrate into the Lower Merion community. Reunited with his twin brother Achille, the two became business partners. The brothers entered “the hardware business” in 1947 and at one point operated “a chain of five hardware stores” (The Philadelphia Inquirer March 6th, 1999). By the mid-1950s the pair sold three of their stores and continued to operate “Ricklin’s Hardware in Narberth and Suburban Hardware in Bryn Mawr” (The Philadelphia Inquirer March 6th, 1999). Both stores remained staples in the region for many years, especially Ricklin’s Hardware which became known for “its ability to cater to the unusual” (The Philadelphia Inquirer December 17th, 1987). Mario and Achille (along with their business partner Ed Ridell) “held on to [Ricklin’s] for more than four decades” before eventually selling the business to Ed’s son, Jed (The Philadelphia Inquirer April 23rd, 2017).

Barone also started a family once back in the United States. In 1959, Barone married Mary Lue Milton and the couple had two daughters, Jocelyn and Beth. Throughout the remainder of his life Barone continued to be a pillar of the community. He was a member of the “Cynwyd Club, Overbrook Golf Club, Ardmore Optimist Club” and the “Main Line Jaycees” (The Philadelphia Inquirer March 6th, 1999). Barone acted as an advisor for the Main Line Jaycees, even accompanying the “Pennsylvania Delegation to the World Congress of Junior Chambers International in Edinburgh” in 1955 (The Philadelphia Inquirer November 7th, 1955). Additionally, Barone remained connected to his heritage (despite the fact that he was imprisoned there) by joining the “Wayne Italian American Club” (The Philadelphia Inquirer March 6th, 1999). Barone also refused to forget his experience in the military, becoming an active “member of the American Legion, Society of the First Division, American Ex-Prisoners of War Organization, Military Order of the Purple Heart and the Disabled American Veterans” (The Philadelphia Inquirer March 6th, 1999).

Barone’s jubilation and relief that he had finally found “freedom at last” clearly represented not only his literal freedom from prison but freedom in the broadest possible sense. Barone’s post-war commitment to his community, family, and businesses demonstrate how he ultimately seized the freedom he so bravely fought and suffered for.

Mariano Barone’s incredible, and agonizing, experience during World War II demonstrates the valor and honor shown by the residents of Lower Merion during the war. Barone’s story is just one of many incredible stories from the hundreds of Lower Merionites who fought in World War II and highlights just how many hidden historical narratives lie throughout Pennsylvania, and the United States as a whole.

Share Your Story

One of the best ways to preserve history is through the tradition of storytelling, and we want to hear from you! Whether you’ve lived in Lower Merion or Narberth all your life or recently moved here, everyone’s got a story to tell. Share a brief summary of your story for a chance to develop it further and see it featured on our site!

Please note that, while we review all submissions, we’re a small team and are unable to reply individually due to the volume received. If we are interested in developing your story further, we will contact you.

Thank you for sharing your story with us!

Milestones Newsletter

Milestones is the email newsletter of the Lower Merion Historical Society. Visit the Milestones page to sign up and view archives of past issues.