The Mills Of Lower Merion

The Rise and Fall of the Mills

The largest waterway running through Lower Merion Township is Mill Creek, a source that bubbles up in Villanova, runs southeast through Bryn Mawr, spills into Dove Lake in Gladwyne, and then proceeds over various falls until it links with a tributary just east of Ardmore. There it turns sharply eastward, and with new replenishment meanders through the lush Mill Creek Valley, separating Penn Valley and Gladwyne, until it empties into the Schuylkill River at Flat Rock Park. For over two hundred years the power of the water in Mill Creek fostered mill industries unmatched anywhere in the Township. The many different mills supplied both local residents and Philadelphians with grain, paper and cardboard, guns and gun powder, lumber, sheet metal, woolen fabric, cotton and woolen threads, and candle and lamp wick.

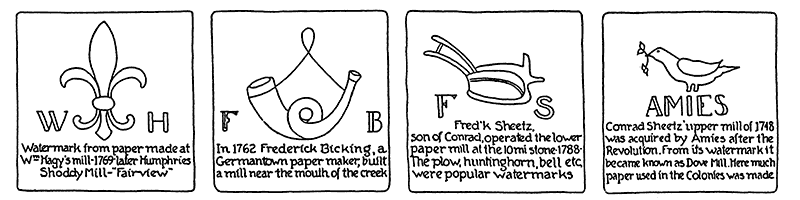

The paper produced by the mills served for America’s earliest documents, currency, and cartridge paper and can be identified by watermarks in archives throughout the country. At least twenty different mill sites along the creek have been identified by documents, standing buildings, ruins, or archaeological remains. For each one a mill pond, dam, raceway, sluices and mill buildings, wheel houses, and intricate mechanisms had to be constructed and maintained by owners and workers. Mill Creek Valley was a bustling industrial site through much of the 19th century. Mill ownership expanded beyond the original Welsh settlers to include families from Germany, Switzerland, and England.

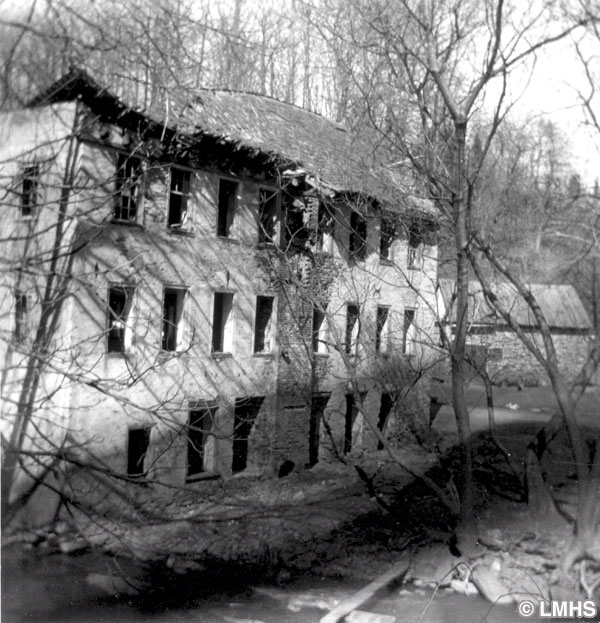

Certain mills, such as paper, grist, and saw mills became uneconomical by the 1850s due to advancing technologies. These closed or were converted to textile mills. More influential in changing the industries was the power of the water that drove the wheels, stampers, mill stones, saws or spindles. It had devastating effects when uncontrolled. Storms and floods frequently destroyed dams and mills, wiping out entire businesses. The flood of 1893 brought the final destruction of most remaining mills on the creek. The one exception was the former Nippes gun factory that had been converted to the Barker Woolen Mill. With a conversion to a water turbine, this mill produced woolen thread into the 1950s and still stands.

Maps and advertisements tell us that at least a textile and paper company retained their land and warehouses into the second decade of the 20th century. But by then Mill Creek Valley had begun to shift from an active mill community with worker tenements, small, stuccoed twin homes, a store and post office at Rose Glen, and the neighboring Reading Railroad line to a quieter, suburban residential community.

As industry moved elsewhere, properties were purchased by wealthy financiers and industrialists for suburban living. New homes were built by turn-of-the-century architects on the hilltops. Mill structures, mill owners’ homes, and modest workers’ housing were converted into serviceable residences for staff.

In the 1920s, for example, James Crosby Brown’s estate grew to 185 acres of former industrial land. After Brown’s death in 1930, the restricted and sensitive development of his estate into three acre lots helped protect the natural environment and established minimal and compatible new residences in Mill Creek Valley. More recent protection has come through Lower Merion Township’s purchase in 1994 of Walter C. Pew’s 103-acre estate to create Rolling Hill Park. Within this natural parkland, stone building ruins along the waterway remain as architectural testament to Lower Merion’s industrial past.