The Pennsylvania Railroad and the Development of the Main Line

More than any other person or entity, it was the Pennsylvania Railroad that built the Main Line. For 111 years, its trains linked Lower Merion with Philadelphia and the nation. Even today, three decades after the railroad merged with a rival, the Pennsylvania’s legacy continues to shape life in the township.

The Pennsylvania Railroad began its long association with the Main Line when it purchased the Philadelphia & Columbia Railroad from the state in 1857. At that time, there were only three stops in Lower Merion: Libertyville (serving modern Narberth and Wynnewood), Athensville (now Ardmore) and White Hall (Bryn Mawr). For a little over a decade, the Pennsylvania concentrated on rebuilding the line and developing long distance traffic. As late as 1869, the railroad operated only a handful of local trains along the Main Line.

As part of the process of relocating its line, the Pennsylvania acquired a number of farms in what was then Humphreysville. The railroad decided to develop this land as both an elite residential community and a summer resort. The railroad renamed the station (and effectively the town) Bryn Mawr. The creation of Bryn Mawr as a haven for the city’s wealthiest residents reflected national trends. A little after mid century, the railroads serving Boston, New York and other large cities began to encourage elite residential development along their lines. The Pennsylvania was a decade (or more) behind the creation of similar railroad suburbs, both nationally and in the Philadelphia region. Although not the first, the Main Line soon came to symbolize the quintessential railroad suburb. The railroad not only encouraged the construction “of homes of more than ordinary architectural taste” but it also built a large hotel to cater to summer boarders. Escaping the heat of a Philadelphia summer by staying in the rural hinterland had been common for the city’s elite since the Colonial period. The Pennsylvania Railroad’s Bryn Mawr Hotel served this market.

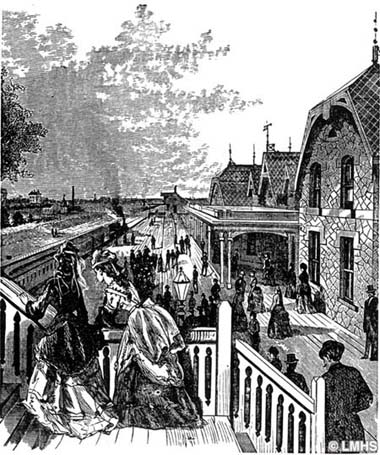

In Bryn Mawr, the Pennsylvania took a direct part in suburban development. Throughout most of Lower Merion, the railroad played a secondary role. Private developers (many with ties to the Pennsylvania, however) purchased farms and subdivided them. To encourage these activities, the railroad built stations and added passenger trains. By the 1880s, the Main Line’s depots were models of Victorian architecture. Passenger service along the Main Line increased rapidly in the late ninteenth century from six locals in 1869 to fifteen in 1874 to over thirty from 1884 onward.

Pennsylvania trains serving Lower Merion carried more than just passengers. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, railroads had a virtual monopoly on land transport. The same trains that hauled passengers also conveyed mail and “express” (a railroad-operated private package service). Pennsylvania freight trains brought coal for heat, lumber for building and nearly everything else to the township for decades.

Starting in the late 1880s, the nature of suburban development in Lower Merion changed. Although large and expensive estates for the wealthy continued to be built, much of the new construction was for middle class families. These new suburbs were products of combined technological and economic changes in the late nineteenth century that made it possible to extend the full range of city amenities to nearby communities. The Pennsylvania Railroad recognized the importance of these services when it declared in a 1913 promotional brochure: “The charm of this suburban life, with its pure air, pure water and healthful surroundings, combined with the educational advantages provided, churches, stores, and excellent transit facilities to and from the city, is manifest.”

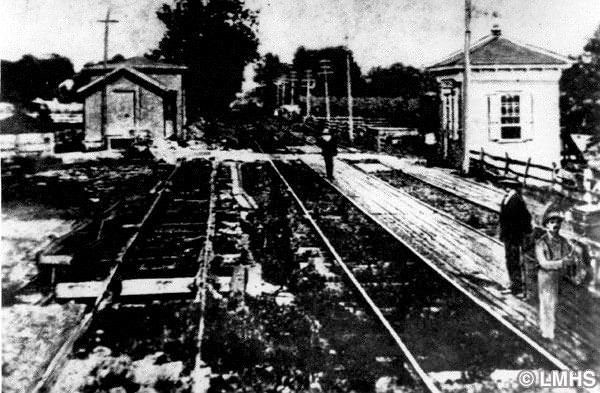

Although pockets of middle class development dotted the township, Bala and Cynwyd on the Pennsylvania’s branch to Reading perhaps best represented this new type of suburb. Within a few decades of the start of train service in 1884, developers had converted sparsely settled farmland into thriving suburbs.

Not everything the Pennsylvania Railroad did benefitted Lower Merion. Following the introduction of electric trolleys in the 1890s, the railroad fought hard to keep this new form of transport from the township. The railroad even purchased part of the route of the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike and installed Alexander J. Cassatt as president of this subsidiary in order to forestall the installation of trolleys along the road. The Pennsylvania was not completely successful, as a trolley line was built to Ardmore through Delaware County in 1902.

In 1915, the railroad electrified its line between Philadelphia and Paoli. The engineering used on this route became the model for the Pennsylvania’s other electrification projects. Eventually these stretched from New York to Washington and west to Harrisburg. The short, red electric cars (known to the railroad as MP-54s) served the township for over sixty years, grinding their way back and forth between Center City and Paoli.

Passenger service on the Main Line outlasted the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1968, the once mighty Pennsylvania merged with its arch rival, the New York Central, to form the illfated Penn Central. The only change this consolidation brought to the Paoli line was the repainting of some of the MP-54s in green. Following the bankrupcy of the Penn Central in 1970, service on the line began to deteriorate. After initially funding the trains, the South Eastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority eventually took over direct operation of the Main Line in the 1980s. Today, the Main Line is one half of SEPTA’s R5 line, the region’s busiest commuter route. Thousands of people still use the trains every day to travel to and from Lower Merion for business, shopping and pleasure.