John Roberts Of The Mill

At the intersection of Old Gulph and Mill Creek Roads is a small group of pre-Revolutionary buildings. Now the Mill Creek Historic District and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, its development was begun by John Roberts, a “yeoman and millwright” from Denbighshire, Wales. In the 317 years since his arrival, much intrigue and innuendo have swirled about the site and its first family. On November 20, 1683 the ship Morning Star landed “upstream” (in Philadelphia) carrying a group of Welsh settlers. John Roberts “of the Mill” or “of the Wain” (wagon) had purchased the rights to 500 acres in 1682 from Penn; he received a warrant on 250 acres in 1702; the patent on the property was granted to his grandson in 1743.

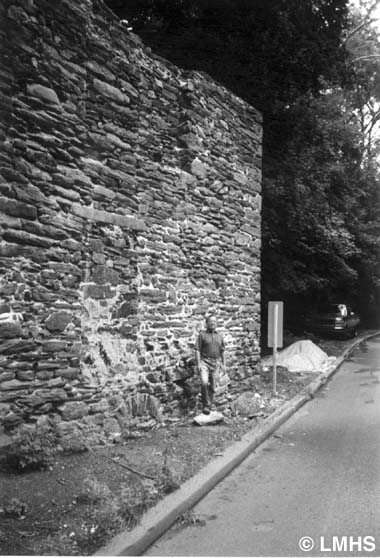

A rushing creek coursed through Roberts’ acreage; a natural waterfall provided power for the mill he would build. No documentation has been found of Roberts’ exact arrival to his land, what his first buildings were or where they were located. Possibly he first constructed his gristmill, lived first in a lean-to against a hillside, then built a more substantial dwelling

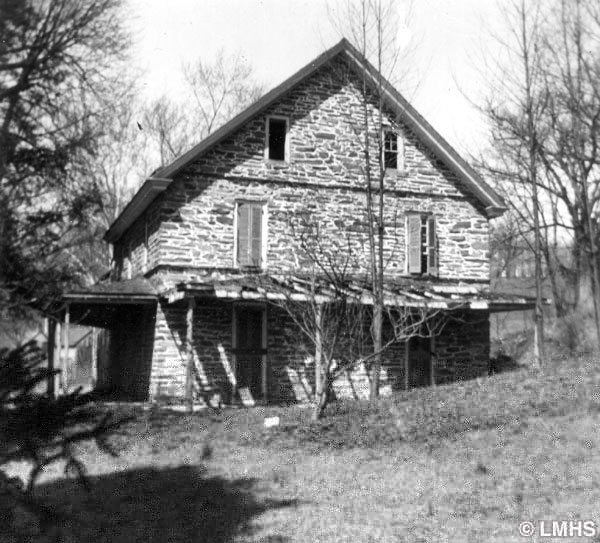

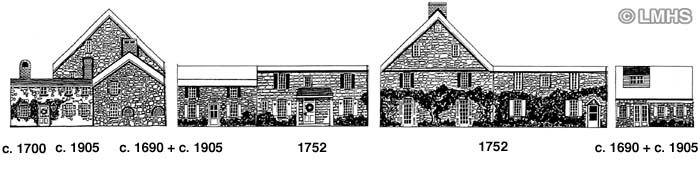

1690 House

Downstream from the mill site stands a house enclosing remnants of a log building. By local tradition called the “1690 House,” a plaque under its peak is of questionable accuracy. An article from a 1905 Chronicle noted that a plaque, appeared “this year” when a log cabin on Mill Creek was “transformed” into a “modern dwelling”.

Some assume this was Roberts’ first home; others question the logic and practicality of his having selected this site. It is 500 feet from his mill, too far downstream by colonists’ standards, and also lies in the floodplain of Mill Creek.

The proximity of the “1690 House” to the 1840 Croft Kettle Mill, directly across the creek, suggests a more likely possibility of its association with that mill.A small double unit is shown on a 1900 atlas of the area. The real history of this building may never be known…and local lore will undoubtedly persist.

Roberts Marries

In 1690 at Haverford Meeting, John Roberts, “bachelor of Wain,” believed to be 60 years of age, married Elizabeth Owen, said to be 18, an age difference not uncommon in those days. As Welsh settlers traditionally built more substantial homes when they married, it is now thought that Roberts built a typical Welsh 1-1/2 story stone house, c. 1690, on a hillside near the mill.

John Roberts sired four children. Roberts’ wife might have died in childbirth in 1699, the reason that no mention of her was made in his will of 1704, the year he died.

John Roberts II

John and Elizabeth’s eldest son, John, took title to his inheritance in 1716 and he married Hannah Lloyd in 1720. Sadly, this young man “sound of mind and memory, but frail of body,” died a year later…four months before the birth of their son, also named John.

John Roberts III

It was this John Roberts who became very prosperous and active in community affairs as the Revolutionary War approached. Roberts III inherited his property in 1742. A year later, he married Jane Downing and, over the next 25 years, fathered twelve children, of whom ten survived past infancy.

Roberts III amassed extraordinary holdings of over 700 acres. Records show that he owned mills and land in neighboring townships and, with partners, had other mills in Maryland.

A New Mill

By 1746, the year he replaced the earlier mill of his grandfather, Roberts had a virtual monopoly on milling in Lower Merion. His mills made flour, lumber, paper, oil and gunpowder. Also, he owned orchards, woodland and watered meadows for his abundant livestock. He would have employed many workers and servants.

An Enlarged Residence

In 1752, John and Jane Roberts built a fine 3-1/2 story addition to the small stone dwelling of his grandfather. It boasted large windows, pent eaves and a balcony sheltering the front door. The original datestone, inscribed “J&JR 1752,” is beneath its east peak. The earlier, c. 1690 house, likely one room with a loft, then became the kitchen, possibly also housing servants. Some dozen rooms held fine furnishings and the necessities of daily living. This manor house, overlooking Mill Creek, was a lovely setting for a family of privilege.

Activism

John Roberts III became a highly respected citizen in the greater community. A Quaker, he was named a trustee in 1763 for purchasing land for the Merion Meeting. By 1758 he had become active in public affairs. Roberts was appointed to a commission overseeing improvement of the Schuylkill River in 1760 and 1773. In 1774 he became a member of the Committee of Correspondence to protest the British government’s Port Bill. In 1775, in opposition to the slave trade, he was a delegate to the Convention for the Province of Pennsylvania.

Unsettling Times

In the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, increasing desire for independence from Britain spurred political maneuverings and personal jealousies. It was a trying time for Quakers; an affluent minority group which opposed war. In late 1777, predominently Quaker Lower Merion was overrun by foraging parties of both the British and American armies, sent to ransack farms and mills for provisions. John Roberts, miller, sustained the greatest losses.

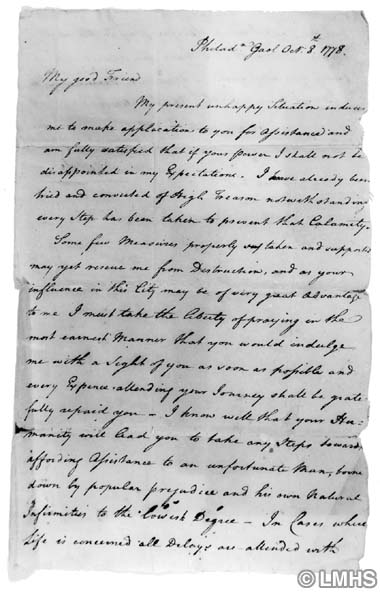

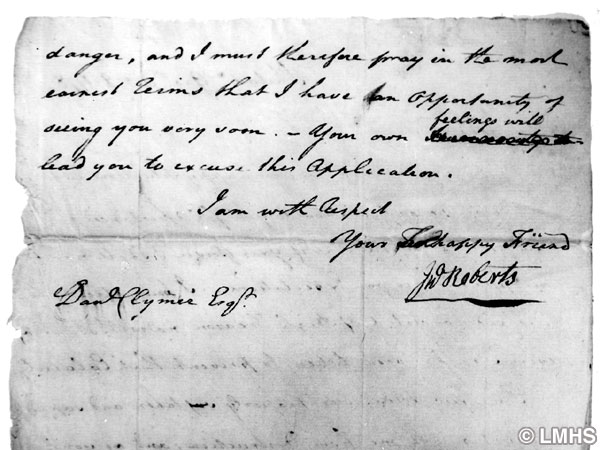

Roberts’ Imprisonment

By 1777, Roberts had received frequent threats “by some malicious Persons in my Neighborhood” claiming he was a Tory. Denying any involvement, he fled to British-held Philadelphia for safety.

Roberts later wrote that American soldiers then appeared at his “Plantation,” threatened and abused his family and stole 64 animals. He said he intended to return home but his family, “who thought my Life in Danger, deterred me.”

While in Philadelphia, Roberts helped imprisoned Americans and did other good deeds. He wrote of threats and abusive treatment by the British army.

At some point he was forced to guide British soldiers on foraging raids in Lower Merion…his only assistance to the British.

Roberts surrendered to the Americans after the British left Philadelphia. On June 19 he affirmed allegiance to the state. It is thought that he aided George Washington about this time by informing him of pending British movements.

Nevertheless, on July 27, based on oaths of neighbors, the Smiths, with whom he purportedly had a land dispute, a warrant was issued for Roberts’ arrest. The charges: high treason.

Perhaps Roberts expected acquittal based on his many good works. But he was arrested with others on August 10 and jailed in the Walnut Street prison. Only Abraham Carlisle and John Roberts were made to stand trial, rapidly convicted and sentenced to die by hanging.

Public Protests

An outcry followed. Petitions were sent to the Supreme Executive Council seeking a stay of execution and leniency for Roberts. The nearly thousand names included prominent Friends, 26 military officers and three signers of the Declaration of Independence.

The entire jury on his trial favored a stay; even Chief Justice Thomas McKean, who presided at Roberts’ trial and vehemently denounced him, asked postponement. Roberts’ children and wife pleaded on their knees for his life.

But the Council was adamant. John Roberts was executed on November 4, 1778.

Lingering Questions

It is said that Roberts’ hanging was “political murder”…he was made an example to discourage loyalists. Certainly he was put to death on slight charges. Interestingly, pertinent documents, including Justice McKean’s notes of the trial, were soon “missing.”

All of Roberts’ estate was confiscated except those items his widow could prove were in her dowry. Its dispersal suggests ulterior motives, too. Four days after purchasing the property, Edward Milner quietly sold it to John Nesbitt and his two partners. Well-known to Justice McKean, the three were advocates of the Revolution. Roberts’ estate would seem a coveted “reward.”

By 1792, an act was passed returning to Jane Roberts any unsold portions of Roberts’ estate and giving her a small pension.

John Roberts’ religious beliefs, great wealth and attempts to hold a middle course in the war probably led to his persecution and death.

Roberts best described his plight in his sad description of himself as “an unfortunate Man, born down by popular prejudice.”

might have been a springhouse.