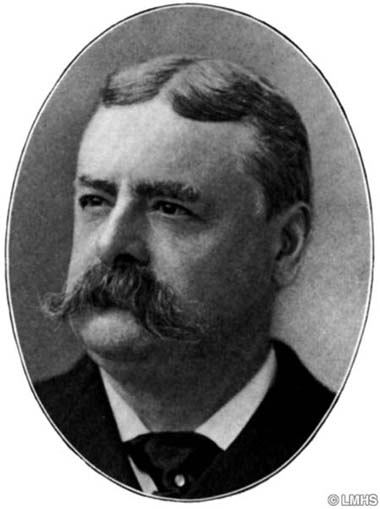

Clement Griscom’s Dolobran

The 1900 book, Fads and Fancies describes Clement A. Griscom:

Few men possess more divergent tastes; he is president of a company that operates one of the largest transatlantic fleets; he is a member of a club devoted to agriculture and breeding blooded cattle; he has been commodore…of a yacht club; he sows and reaps his own crops, and takes prizes at county and state fairs for his horses, cows, and sheep.

The remainder of the article speaks of his various national and international honors, but little of his amazing estate.

An Evolving Mansion

The house is the work of the firm of Furness and Evans between the years of 1881 and 1895. During this time, there was constant construction, as the plan and variation of styles shows a distinct evolutionary trend.

Much of the building occurred to house his growing collection of Old Master and late 19th century paintings. After his death, the inventory of an auction of his collection lists works by Rembrandt, Canaletto, Constable, van Dyck, Monet, and the sister of one of his neighbors, Mary Cassatt.

The Dolobran estate grew to almost 150 acres over a 15 year period. The grounds contained formal and informal gardens, farm buildings and pastures, and a golf course. The main house shows Furness working in the “stick style,” a mode favored for resort architecture, and practiced by his mentor, Richard Morris Hunt, in his Newport cottages.

Hunt was the first American architect to study at the Ecole de Beaux Artes in Paris, and Furness studied at the studio Hunt established in New York in the 1850s. Allen Evans was the son of a doctor and land speculator who bought property along Gray’s Lane in Haverford. He developed the land for himself and others, notably Alexander Cassatt.

Evans began his apprenticeship in 1872, and became his partner in 1881.

By the mid 1880s, the house had doubled in size and was sprouting towers and the Furness trademark chimneys. By 1890, the “shingle and stick styles” were giving way to more substantial stone construction.

Dolobran encompassed a floor area of over one half acre spread across five levels as the house rambled across the gently sloping site. The building that remains is a fascinating chronicle of changing tastes of the late Victorian era.

Upstairs. Downstairs.

Just as the exterior evolved from earlier less formal resort styles to a more classical mode, so did the interior changes. For a house of it’s overall size, the individual rooms are not particularly large, except for the 40 x 50 foot gallery/ballroom addition at the rear.

Throughout the home were collections from Griscom’s world travels: exotic glass, porcelain, Delft tiles, a painted canvas ceiling in the manner of traditional Oriental art, intricately carved wood paneling.

The upper floors contained a master bedroom suite with two bathrooms, and bedroom suites for each of the Griscom’s five children. A three story service wing contained a warren of servant’s rooms along with a large kitchen and larder with three built-in tiled ice boxes.

Clement Griscom lived in the house for over 30 years, but when he died, the landholdings and ancillary structures were rapidly sold off, and most demolished.

The main house, hopelessly out of style in the Colonial Revival age, sat empty for many years. Many objects were stored in the sub-basement. During the restoration preceding the Vassar Showhouse of 1990, many original pieces were re-installed, and the exterior was returned to its original appearance with wood shingling, green trim, and a copper-edged roof. Since the house was commissioned by such a prominent Philadelphian, and reflects so many periods in the architectural practice of Furness and Evans, it is a priceless relic of the Gilded Age on the Main Line.