The Soldiers

A Motley Mix

They were the weaver, boatman, puddler, painter, stonemason, and laborer; city

dwellers, mostly from Philadelphia, farm boys and immigrants, primarily Irish

and German; Camp Discharge reflected the Union Army’s social mix. The Civil

War brought them together as a volunteer force—and threw them into the

most horrific battles: Antietam, Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, the Wilderness,

Chancellorsville, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, even Sherman’s March to the Sea.

Their experiences in combat, and for many, of prolonged captivity, left them

older than their years.

Discharge; fifty-nine were Andersonville survivors. Fourteen of the men were

from its Co. H, pictured above early in the war.

Library of Congress

What Became of Them?

Some went on to become leading citizens of their communities while others were

wanderers. Some had abundant family lives and others languished on society’s

margins. Some died young. Others lasted well into their eighties. From pension

files, diaries, biographies, newspaper accounts, census records and other

documentary evidence Back From Battle chronicles the postwar

lives of 23 individual officers and enlisted men of Camp Discharge. Below is a

sample of those profiles.

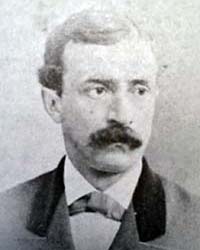

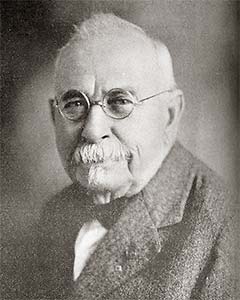

Joseph Corson

Joseph Kirby Corson of Plymouth Meeting, the camp’s assistant surgeon, went on

to practice medicine with his father for a time but soon rejoined the Army. He

was a military surgeon until 1897, serving at Army posts around the country.

From New York City he was transferred to Carlisle, Pa., then Wyoming,

Nebraska, and back to Wyoming. From there, in order, to Alabama, upstate New

York, Arizona twice, Missouri, and Washington, D.C. Corson’s western exploits

included fossil digs with visiting paleontologists. He even had three fossils

named after him, “my only chance for immortality,” he quipped in his memoir.

He also played a part in the improved training of the medical corps.

Corson retired with the rank of surgeon—and in 1899 was awarded the

Medal of Honor for bravery for his rescue of a wounded soldier under fire at

Bristoe Station, Va., in 1863, when he was with the 35th Pa. Infantry.

Corson wrote his memoir

in 1910 and died three years later, at age 76. He is buried in

West Laurel Hill Cemetery.

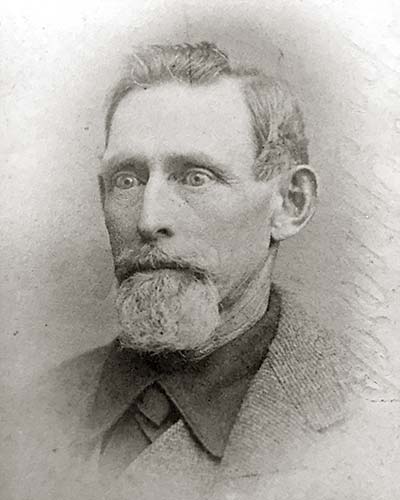

Mark McCusker

Mark McCusker would undergo the trials of Job. The Irish-born weaver had

enlisted in the 69th Pa. Infantry in 1861, at age 26. A year later, during the

Battle of Antietam, an exploding shell wounded him in the right hand, back and

thigh. The hand was left partially paralyzed. In June 1864, McCusker was

captured during action at Petersburg, Va., and shipped to Andersonville. There

he would suffer permanent eye damage that doctors later diagnosed as “atrophy

of the optic nerves.” Another survivor who had known McCusker at Andersonville

told a pension examiner that countless prisoners suffered swollen eyes from

lying on the damp, cold ground without shelter. The problem was exacerbated by

caustic wood smoke from the cooking fires they would tend. McCusker was freed

from Rebel hands in April 1865 and discharged from the army two months later.

He returned to Philadelphia, married, and found work as a weaver—but he

would find no peace. In 1880, his employer told a pension examiner that

McCusker’s eyes “gradually became diseased, a greenish blue scum coming over

the balls of each eye,” and his work deteriorated. By 1883 McCusker was living

in an almshouse in South Philadelphia, a jobless alcoholic with “the

appearance of a tramp.” Because the Camp Discharge medical team had treated

him as an outpatient, they’d kept no records on him—so the pension

examiner decided there was no conclusive evidence that his impairment was due

to his service. McCusker’s application was still pending when he died in 1885,

at age 50, of “dilatation of the heart.”

By the end, the treating doctor said, “he lived mostly on bread and water and

rum. He was a poor old broken down man.” McCusker’s wife had died two years

earlier, the cause listed as alcoholism. They left behind two destitute

children who were put under the care of Orphans Court.

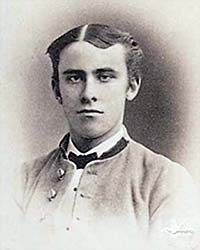

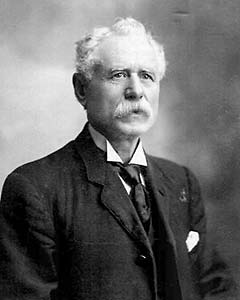

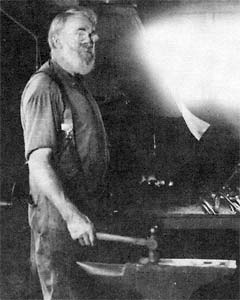

Albert Thalheimer

Albert Thalheimer burned with purpose after the war. His German Jewish family

had brought him to the United States as a boy, leaving the murderous

anti-Semitism of the old country behind, and settled in Philadelphia. In July

1861, when he was 19, Thalheimer joined the 23rd Pa. Infantry, the colorful

“Birney’s Zouaves.” Three years later, he fell into Rebel hands at the Battle

of Cold Harbor, Va. Nine months of privation at Andersonville followed, during

which he lost nearly one hundred pounds. He began to recuperate at a Union

hospital in Vicksburg, then spent three weeks at Camp Discharge before

returning to his family in Philadelphia.

From there a renewed Thalheimer migrated to Reading to establish himself as an

entrepreneur. He opened a dancing school first, then an organ factory. The

breakthrough came with cigar boxes. Manufacturing them brought wealth and

prestige, and seats on Reading’s Board of Trade and Chamber of Commerce.

But Thalheimer never lost touch with fellow veterans. Newspapers reported on

his leadership in the local Andersonville survivors association and his hiring

of a half-dozen aging or disabled Civil War vets for light work at his factory

(a number that grew to fifty men). He lobbied senators on behalf of an 1890

bill broadening veterans’ pension rights, saying that “he himself is not

dependent on the bill but he speaks for many who are.” Further, he offered his

G.A.R. post a tract of land and the stones to erect a soldiers monument on the

western slope of Reading’s Mount Penn, and donated another tract for

construction of an “old man’s home.”

Thalheimer retired in 1911 and died twelve years later at age 81. His obituary

in the Reading Times lauded him as “one of the city’s public spirited

citizens.”

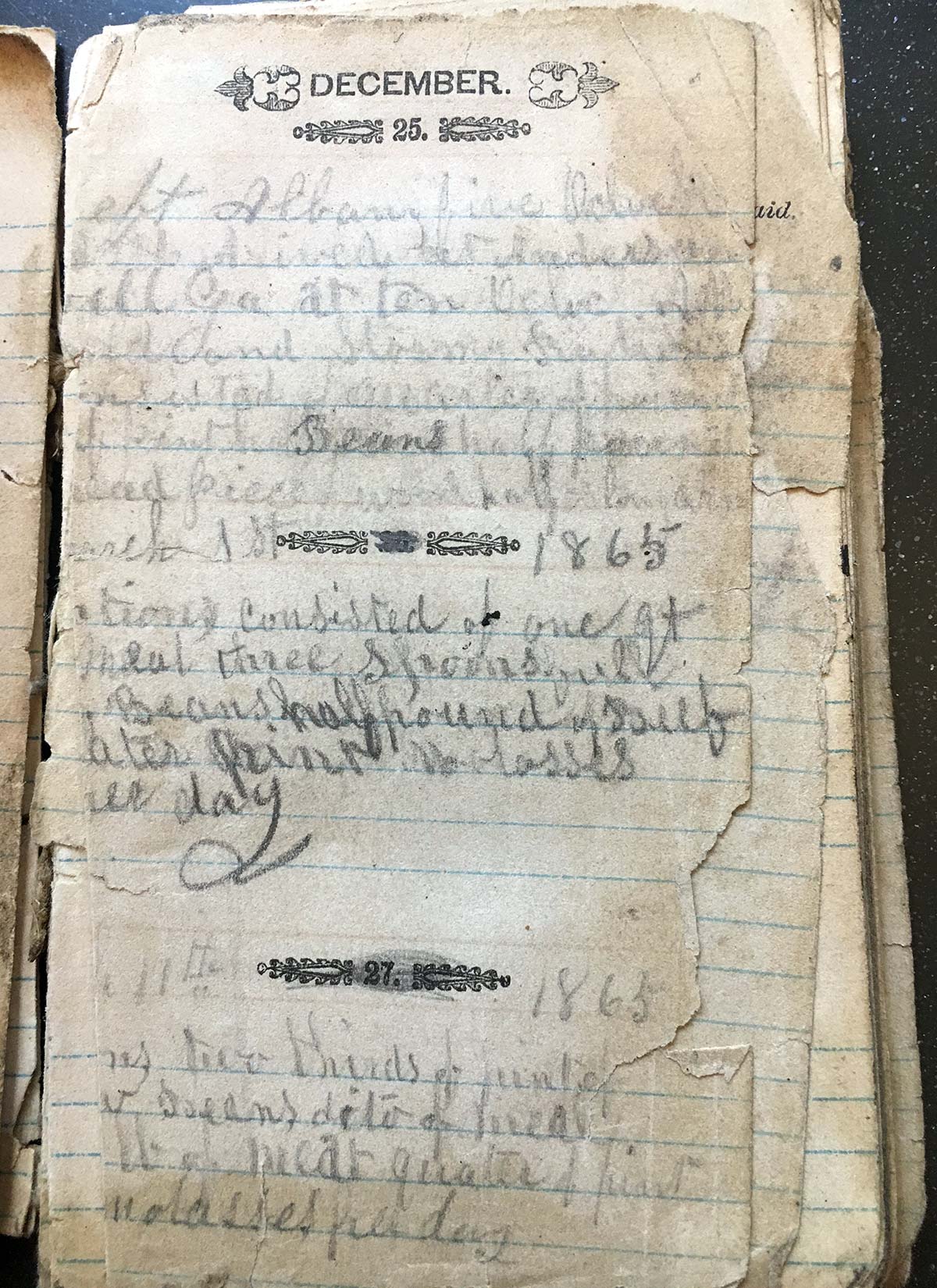

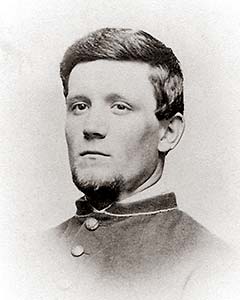

Isaac Horner

In early 1864, Isaac F. Horner was a Philadelphia produce dealer residing in

Camden, married with four young children, a fifth newly born or on the way,

and a personal estate valued in 1860 at $13,000 in 2021 dollars. Nevertheless,

he enlisted in the 72nd Pa. Infantry, part of the vaunted Philadelphia

Brigade. Perhaps the 36-year-old was drawn to the brigade’s fame, or to the

late-war bounty of $575, more than his estate estimate. In any event, Horner

ended up doing hard duty—shot in the right hip at the Battle of

Spotsylvania, captured at Petersburg, sent to Libby prison and on to

Andersonville. Horner carried a small “soldier’s diary” with him to record his

ordeal, though its penciled entries became less legible as it, too, endured

rugged conditions. After nine months at Andersonville, Horner made his way

north and was processed through Camp Discharge on July 12, 1865. He rejoined

his wife Lydia and their five children in Camden, N.J. Their family grew to 7

children by 1872.

Andersonville. National Archives

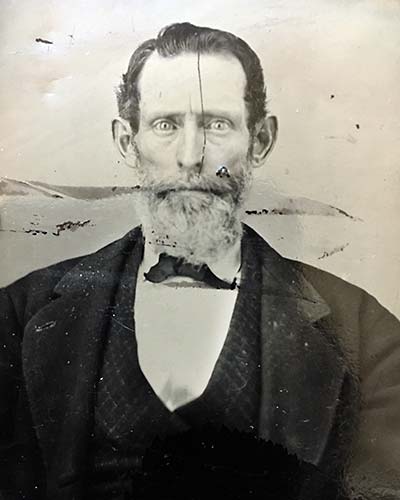

Then on December 12, 1879, Horner vanished. His family received two letters,

from Harrisburg and Columbus, Ohio, that advised against trying to track him

down, then silence. Lydia struggled financially in her husband’s absence, and

in 1890 applied to get a widow pension. She was denied because she couldn’t

establish if he was alive or dead.

Yet Isaac Horner was very much alive. He had boarded a train with $300 ($7,800

in 2021 dollars) borrowed from his brother and mother. After a year of

wandering, he took on a new existence in rural Thornville, Ohio, 30 miles east

of Columbus. Lydia would know nothing of his whereabouts until she opened a

1901 letter that disclosed the recent death of her husband. The writer,

William Neel, explained that Horner had come to live with the extended Neel

family in Thornville in 1881. “Isaac was one among us and perfectly at home at

either of our Houses,” Neel wrote. Horner worked on the Neel family farms,

sawmill and brick and tile factory, and helped to care for William Neel’s

aging parents. But then, in the winter of 1901, he fell ill and died of

pneumonia.

pension file. National Archives

Had Horner confessed his secret to the Neels? Did they stumble upon it later

in his papers? Either way, in a round of cordial letters, William Neel and the

Horners exchanged photographs of Isaac, as well as invitations to visit one

another. The Neels submitted affidavits in support of Lydia Horner’s renewed

widow-pension claim. She was being cared for by her adult children by then and

died in Camden in 1906 at age 78. There is no record that she ever received

the pension.

In Their Own Words

Later in life, a handful of Camp Discharge soldiers wrote memoirs of their war

experiences. Click on the four men’s photos below to be redirected to their

individual memoirs, which are posted online.

Pvt. Michael

Pvt. Michael Pvt. Aaron E.

Pvt. Aaron E. Sgt. John J.

Sgt. John J. Pvt. Samuel B.

Pvt. Samuel B.