The Camp

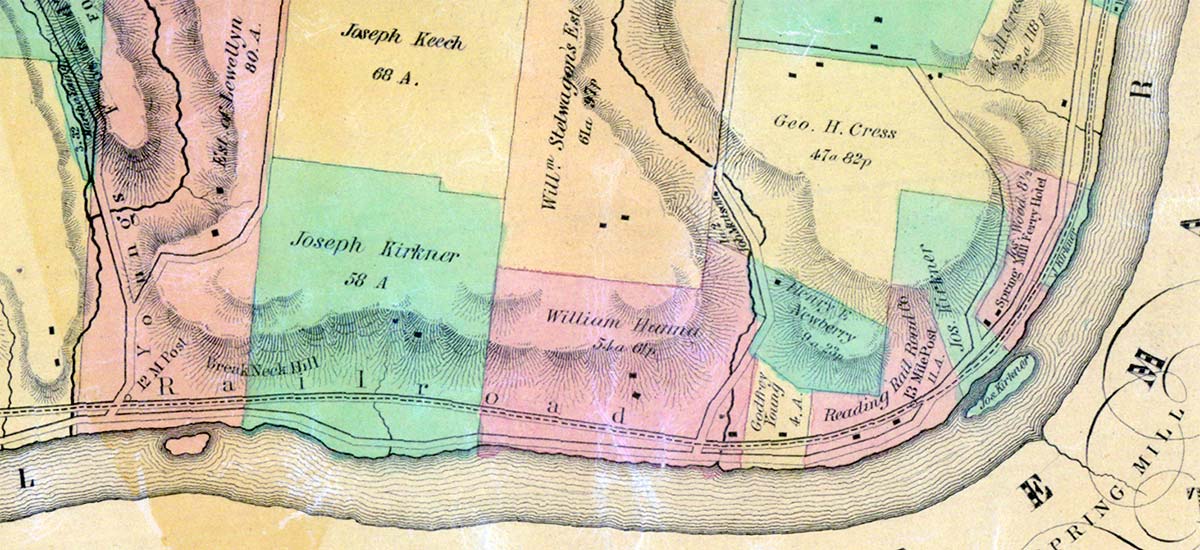

Local farmers called the rural promontory above the Schuylkill River “Break

Neck Hill.” At the time of the Civil War, the land belonged to farmer Joseph

Kirkner whose old stone farmstead sat on the wooded slope. Beyond the bluff

were fields of crops and grazing land; Merion Square (Gladwyne today) was two

miles to the southwest. The site was isolated, and to military eyes that made

it useful.

Young’s Ford and Spring Mill Roads.

Map of the Township of Lower Merion (J. H. Levering, Philadelphia, 1851);

Lower Merion Historical Society

The Army Moves In

In June 1864, the War Department ordered that a special camp be established

near Philadelphia to house up to two thousand Pennsylvania troops. The war was

still raging in the South, but there was another urgent concern. Tens of

thousands of Pennsylvania men had volunteered back in 1861 for three-year

enlistments—and their discharge dates were coming due.

While some of them would re-enlist, most were eager to be mustered out and

return home. A site team selected the Gladwyne locale for the mustering-out

camp because its very remoteness would limit the soldiers’ access to taverns

and other urban temptations, and prevent “camp diseases” like smallpox and

typhoid from spreading to the general public. Plus, the Reading Railroad line

abutted the property along the river flats, guaranteeing ready access to

Philadelphia.

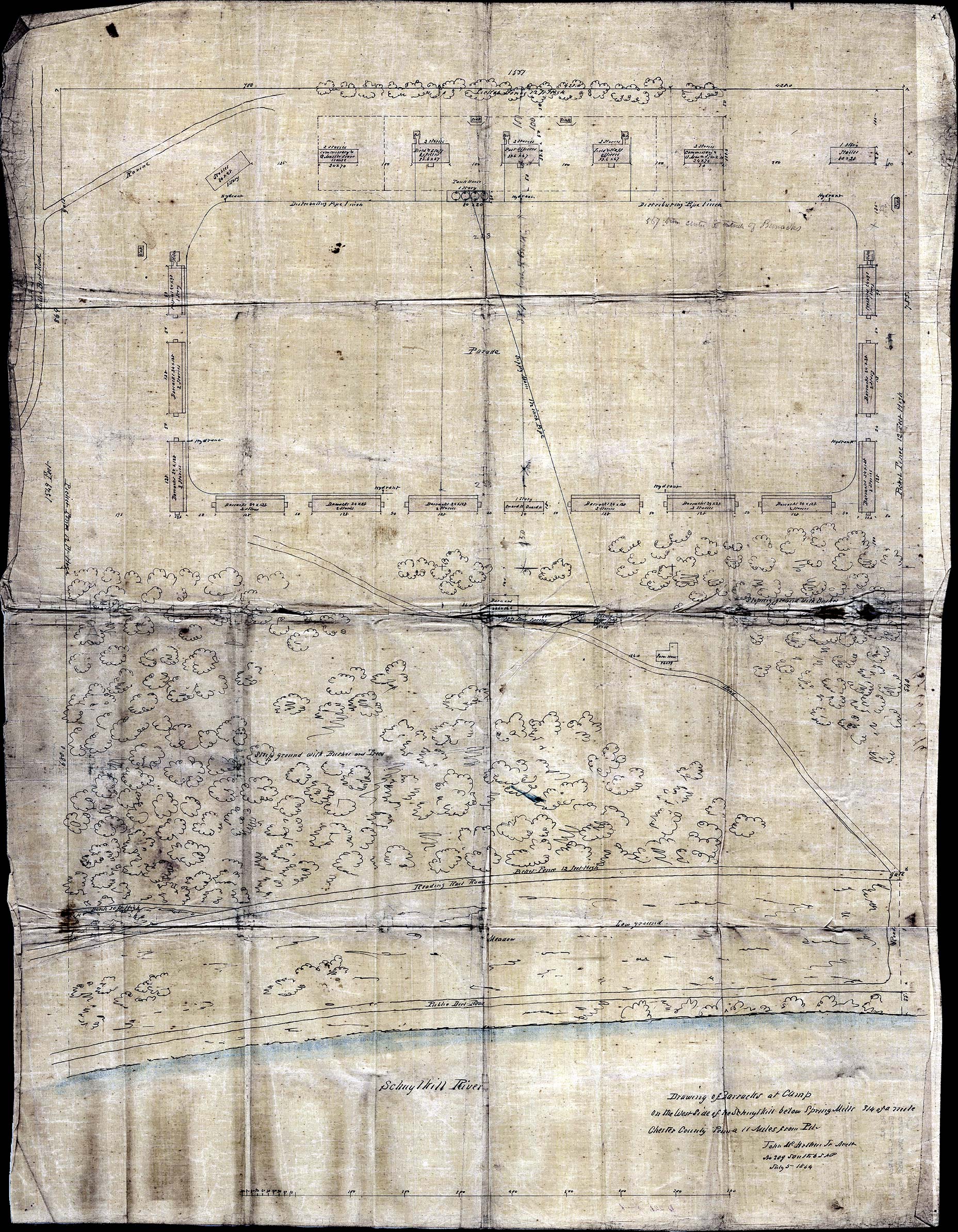

July 5, 1864”. Architect’s drawing on cloth National Archives

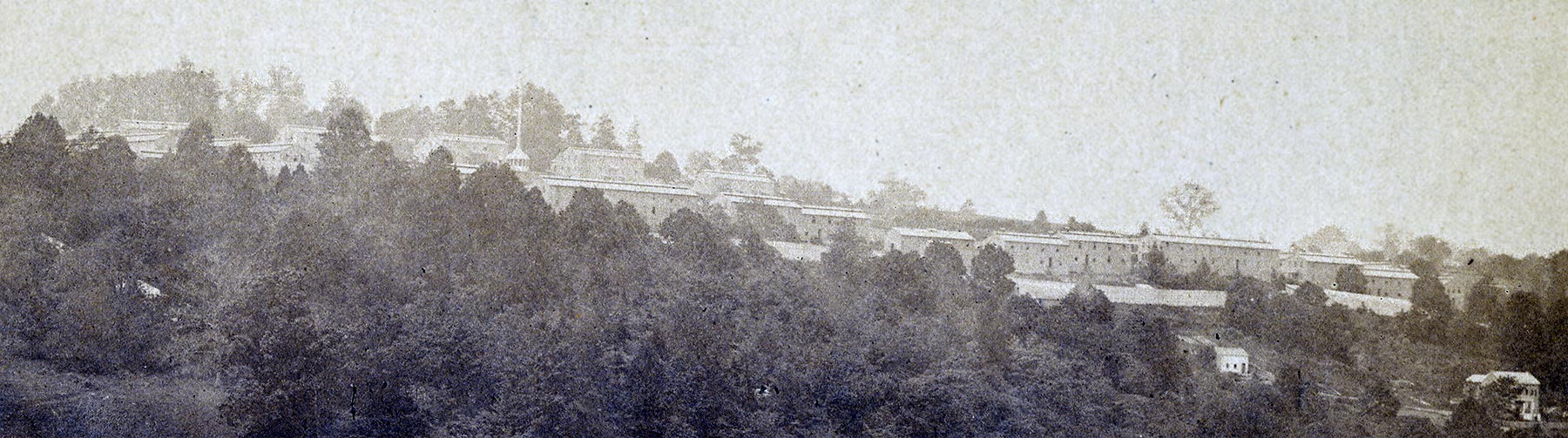

The Army leased the land and erected a quarter-mile-square campus of buildings

enclosed by a high stockade fence. Local workers provided the materials and

labor. A command staff and a force of garrison guards were brought in, and in

October 1864, Camp Discharge was officially opened. By then, scores of weary

young servicemen had already arrived for muster-out. They were the first of

1,118 soldiers from 89 Pennsylvania regiments who would transit the camp

during the eventful coming year.

opposite Spring Mill, Montgomery Co., W. B. Powell).

The image can be scrolled horizontally.

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The Problems Begin

Most of these servicemen were different. Unlike other “three-year men” who

were being mustered out en masse with their regiments, the soldiers sent to

Camp Discharge were “strays”, separated from their units in the field due to

capture, hospitalization or detached duty. Unfortunately, that also meant

separated from their officers and paperwork. Finding and finalizing paperwork

to officially clear an individual for muster-out was a slow, arduous process.

As the strays waited in administrative limbo, performing make-work tasks and

killing time, their restlessness could turn to anger. One man wrote his

congressman to blast Camp Discharge as “without any exception the most

miserably conducted camp I ever saw.” The barracks quickly became “a growler’s

paradise.” As men went AWOL to local saloons, or to visit their families in

Philadelphia and elsewhere, the camp guards increased their patrols and the

guardhouse filled up with violators. Fortunately, the steady outflow of men

who’d been successfully discharged helped to keep hopes up for the others.

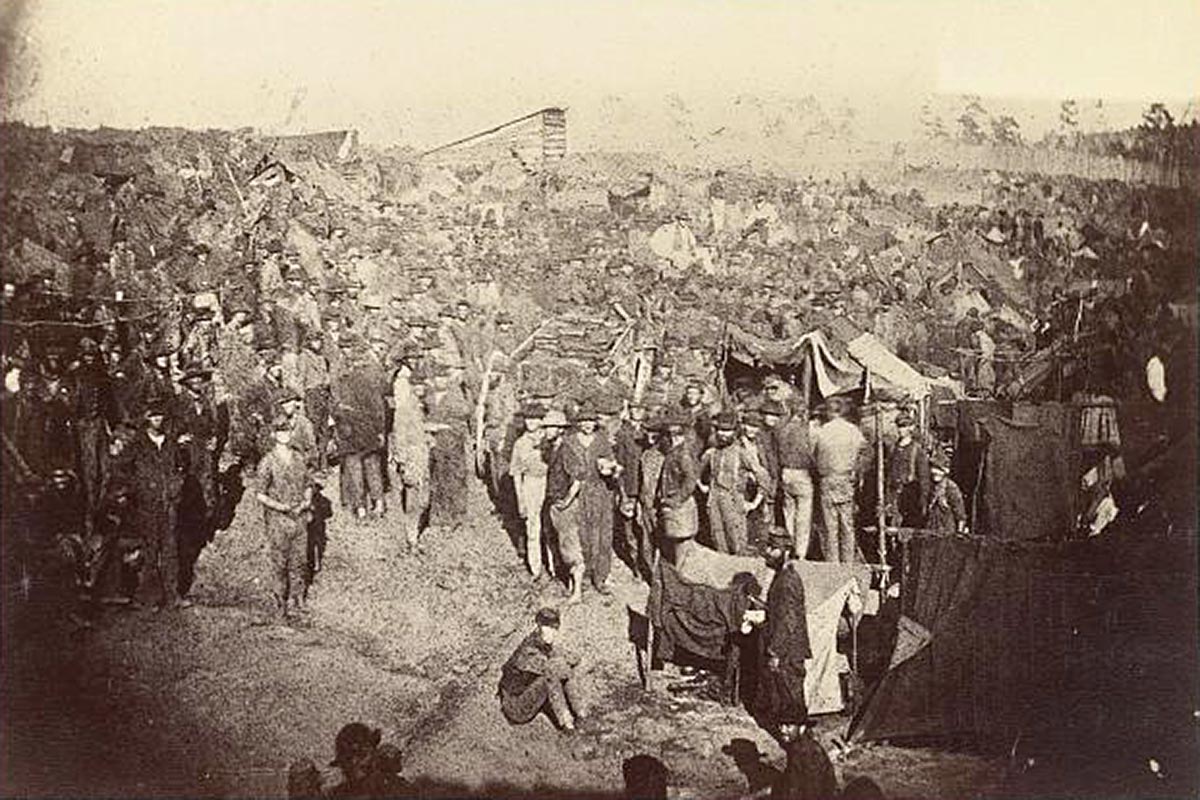

The Physical Wrecks

According to the book Back From Battle, more than three hundred

of the stray men had straggled north after being released from the wretched

Andersonville prison in Georgia. Many of them were at death’s door, and had

seen comrades succumb at Andersonville and other Confederate prisons.

Library of Congress

Courtesy Historical Society of Montgomery County (Pa.)

Camp Discharge had an understaffed hospital that would log in more than eight

hundred patients—”a collection of broken down men who required a great

deal of work,” wrote staff doctor Joseph K. Corson, of Plymouth Meeting.

Ailments ranged from pestilent smallpox and typhoid to an assortment of

lingering lung, skin and intestinal diseases. Other men, especially the camp

guards, showed up with venereal diseases. Medical treatments of the day were

often ineffective (castor oil), dangerous (mercury) or addictive (opium). A

few ailing soldiers died at the camp, while others would go on to lead

woefully curtailed lives.

In the Thick of It

Courtesy U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, Pa.

The daily train brought a flow of new arrivals and carried away more and more

of the discharged during the winter months of 1864-65. The camp commandant,

Col. John Hancock of Norristown, endeavored to improve the camp’s operations

and morale. At the same time, Hancock undertook some pet projects to dress up

the camp—and his own quarters—that caused friction with his staff

officers. Military records chronicle outbreaks of squabbling at the camp

headquarters. One supply officer actually faced a court-martial for

insubordination. Hancock pressed on with his projects, even though an Army

inspector criticized them as costly and indulgent. Meanwhile, North-South

prisoner exchanges were resuming in full, resulting in ever more woebegone

arrivals at the camp and its hospital.

The Turning Point

April 1865 saw dramatic events. Confederate commander Robert E. Lee

surrendered at Appomattox and the camp’s decorative brass cannons were fired

across the valley in celebration. Six days later, President Lincoln was

assassinated. As Lincoln’s bier traveled from city to city, a contingent from

the camp served as an honor guard in Philadelphia. The war’s end brought an

order to quickly demobilize the Union’s huge volunteer army and cut costs.

Military hospitals cleared out as many patients as possible. Newer enlistees

were mustered out even before their one-year and two-year terms were complete.

Camp Discharge went from discharging 68 soldiers in April to 85 in May to 252

in June. In July the camp was ordered closed. Hancock and his team departed,

replaced by a small caretaking force. The Army held a public auction of all

the camp contents—every board, shingle and horse trough—that

efficiently cleared the premises.

The Aftermath

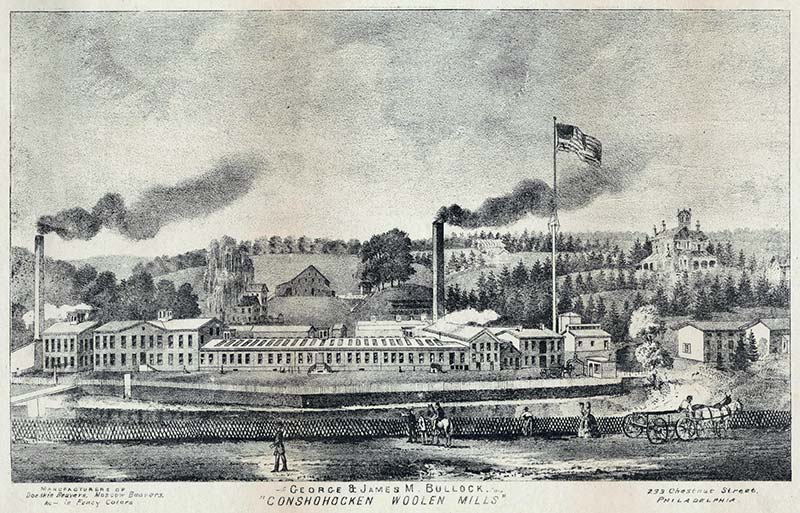

Some of the camp’s wooden structures were moved to mills in nearby

Conshohocken and put to new use. The Balligomingo Woolen Mill erected the

camp’s huge flagpole on its site, where it towered until a fire consumed it in

1889. The Camp Discharge acreage reverted to its owner, who put it back to

farm use.

this 1875 print.

Courtesy

Library Company of Philadelphia

The property would change hands several times over the next century but would

keep its bucolic character as a mix of crop land, pasture and woods. In the

1880s, iron magnate Howard Wood built a summer estate on an adjacent point on

the ridge and dubbed it “Camp Discharge” to keep the name alive. For years his

son Clement put the land to renewed military use by holding encampments of his

First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry unit.

Courtesy Alan Wood

Gladwyne Library

By the mid-1960s the Wood estate house was gone and the old Camp Discharge

grounds had become the private property of the Philadelphia County Club. Today

the club’s Centennial Course runs across the camp’s upper end. The slope down

to the Schuylkill—the old Break Neck Hill—is a wooded buffer, its

history unmarked.