Rediscovering Camp Discharge

Visiting the Site

The Camp Discharge location is privately owned and off limits to the general

public — except for a lone, legal avenue of access for the hiker, the

Sid Thayer trail, a blazed footpath (0.9 miles one way) that is part of Lower

Merion Township’s Bridlewild Trail system.

The walk offers views of the Schuylkill River (and Expressway) and takes you

into a corner of Lower Merion where remnants of our 18th and 19th-century

farming heritage persist. You will see several dry stone walls that demarcate

170-year-old property lines and the remains of Joseph Kirkner’s farmhouse,

barn and springhouse that predate Camp Discharge.

Camp perimeter

Parade ground

Sid Thayer

trail (public access)

farm lane and building ruins

audio description location

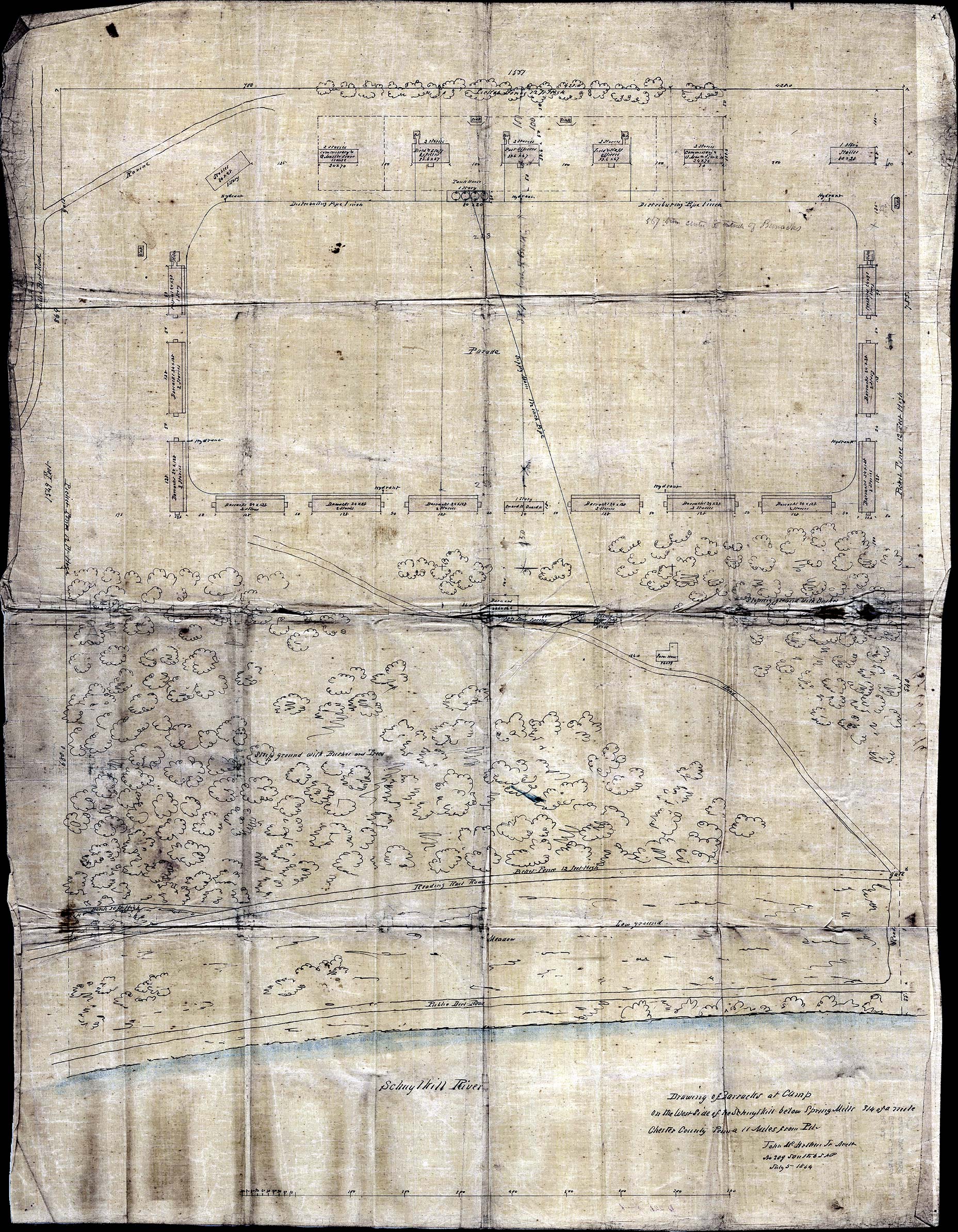

The Camp perimeter and parade ground are based on locations and

measurements in the

1864 architect’s plan.

Our trail description starts from

Riverbend Environmental Education Center, at the eastern end of Spring Mill Road in Gladwyne.

-

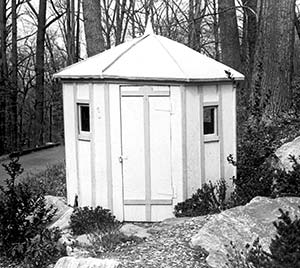

From Riverbend’s parking lot, look uphill to spot the last remaining Camp

Discharge structure, a small wooden sentry box. It was moved to this

location by the Wood family from the Camp’s Reading railroad gate.Downhill and across the street is the entrance to the Sid Thayer Trail,

marked with a sign. The trail curves across the wooded hillside as it

heads south, paralleling the Schuylkill River below, and a 19th-century

stone wall above. -

Pass through a grove of bamboo, cross a wooden footbridge, and you have

reached the camp’s perimeter. In 1864-65 it was marked by a 12-foot high

picket fence.Soon thereafter, another path merges from the right side. According to the

architect’s plan, you would now be standing amongst the barracks that

enclosed a corner of the Parade grounds, once above you up the slope,

overlooked by an enormous flagpole.

Top to bottom: barracks, farm buildings, railroad tracks, river.

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

-

Less than 100 yards straight ahead, the tumble-down stones of Kirkner’s

barn and stable come into view on the left. The barn was enlarged by the

Wood family, who owned the Camp Discharge site from the 1880s to the

1960s, and quarried the area on the trail’s other side. Past the barn on

the left, a downhill fork switches back, following the 19th-century farm

lane, which once led all the way to the river road and train tracks, but

now is cut off by the Expressway. Beyond the barn you encounter the

springhouse which supplied the camp with water, then the farmhouse which

housed the camp commandant Col. John Hancock and his family.Author Jim Remsen describes the ruins in front of you and this spot in

1865 (2:09 audio).

Transcript

Notice the tumble-down foundation in front of you. It is all that

remains of a small stone barn built by the original white settler in

the early 1800s, and of a larger barn for horses that was built

alongside it in the 1950s. A few yards to the left of those ruins, and

also below you, is the rubble of the settlers’ old stone springhouse.

The Army hoped the water from this natural spring would meet the

camp’s needs, but it fell short and they had to pipe in creek water

from nearby. Farther down the hill is the foundation of the original

settler farmhouse. The commandant of Camp Discharge, Colonel John

Hancock, made this stone farmhouse his residence and actually brought

his wife and children to live there as well. Beneath all these ruins,

an old access road ran from the Reading Railroad stop up what was

called Break Neck Hill to the camp complex behind you, from lower left

to upper right. It would have been a busy byway for men and supplies

arriving and leaving on the daily train down below.Now turn around and face the uphill slope. A long line of imposing

two-story barracks buildings ran hundreds of yards across this rocky

slope, turned the corner at each end and continued up and over the

crest. The camp’s two hospital buildings were at the upper ends, while

the headquarters and supply buildings ran across the very top to

complete the square. In the middle of it all was a large and uneven

parade ground. Here and there was a network of latrines that served as

refuse pits and dumps. These latrines have yielded a number of

artifacts, from bullets to buttons to pig bones.If you are coming from the Riverbend parking lot, continue on the

trail and head uphill. At the top is another marker where you can hear

more about the camp. And be sure to stay on the trail at all times. -

Back on the main trail, as it curves uphill to the right, you enter onto

the camp’s Parade.The plans for Camp Discharge, dated July 5, 1864, were executed by

architect John McArthur Jr., who 7 years later designed Philadelphia City

Hall. McArthur’s plan covers almost the entire Kirkner property, which

bordered Lafayette road, edge to edge, from the stone walls on the hill

crest down to the Reading Railroad track.Further investigation may reveal how closely actual construction of the

camp matched the plan. If it did match, the parade stretched all the way

to present-day Martins Lane, and the hospital and barracks along its edge

lay on the location of #1709-1725, built in the early 1960s. 1724 Martin

Lane, at the end of the cul-de-sac, would correspond to the downslope line

of barracks.Listen to author Jim Remsen describe the 1865 view from the top of the

hill (1:20 audio).

Transcript

You are standing on the grounds of a nearly forgotten Civil War post.

Camp Discharge had a special mission: to handle stray Union soldiers,

all Pennsylvania volunteers, whose terms of duty were expiring. Many

were in bad shape from battle wounds or imprisonment. In fact,

virtually on this spot stood one of the two hospital buildings that

treated a constant caseload of men.You are standing at one side of a square-shaped complex of wooden

barracks, headquarters and supply buildings. As you face the

historical marker, imagine the buildings running downhill to the right

and into the woods, then turning left and continuing across for

several hundred yards, then turning back uphill in the distance. Off

to your left was the headquarters and the officers’ quarters. And in

the middle of this quadrant was a large, open parade ground where the

men would assemble for daily roll call. The parade ground featured two

ceremonial brass cannons, which boomed across the valley in April 1865

to celebrate the war’s end. It also featured an enormous flagpole

that, it is said, could be seen for miles around.

The trail merges with a service road. You can take the road to the right

to loop through the center of the parade, back to the fork described

earlier, with views over the golf course, fields and more stone boundary

walls. Straight ahead, the trail turns sharply left at Kirkner’s property

line and the camp’s western perimeter, still marked by the dry stone wall,

overgrown or buried in spots. It is a short walk down to Martins Lane,

where on-street parking is possible.

the trail, steps outside the farmhouse, back wall of the farmhouse.

Center: a cut stone gutter section

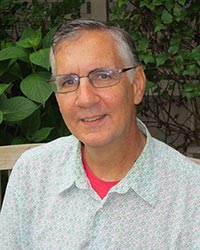

A Native Son’s Journey

Most people, even those living nearby, have no idea there was once a Civil War

post located here. But Brad Upp knew. During his boyhood in Gladwyne, he read

about the camp, hiked the area with his friends and vowed to learn more.

In the book Back From Battle, Brad tells the full, entertaining

story of his Camp Discharge journey. He moved away, became a Civil War

re-enactor and took up metal-detecting on Civil War sites, mostly in the

South. Back in Gladwyne, Brad began uncovering artifacts. His excitement grew

when he located images of the camp roster, and the singular old photo of the

camp itself, seen in its glory from across the river. Jerry Francis, president

of the Lower Merion Historical Society, helped him secure limited permission

from The Philadelphia Country Club, owner of the property, to continue

metal-detecting on the grounds. Even more relics emerged.

Partners in Research

Jerry saw the makings of an exciting project with much wider interest. He

reached out to Lower Merion resident Jim Remsen, a retired journalist who had

already researched and written

two books about other forgotten aspects of local history.

Jim and Brad plunged into a fruitful two-year research sojourn. They visited

archives in Philadelphia, Harrisburg, Wilmington, Norristown, Chester and

Washington, D.C. It proved an emotional experience, too, from the ecstatic

(uncovering blueprints of the camp and its buildings) to the sobering

(encountering the suffering and struggles revealed in military pension files).

Writing and Digging

One of Jim’s goals was to identify the Camp Discharge men who had survived

imprisonment at Confederate hands. By the time the book was published, Jim’s

POW list stood at 490 men, 44% of the 1,118 soldiers mustered out at Camp

Discharge. Brad and Jim investigated each of those 1,118, plus the 642 who

served at the camp as garrison guards. The

massive roster names and profiles each of those

men.

Jim pulled all their information together into a book-length narrative that

chronicles the camp, its men, and its place in military and local history.

Brad functioned as editor and fact-checker, and scoured the internet for

images of the Camp Discharge men. All the while, Brad continued his

excavations at the camp site—outings that continue to this day.

rings

.

.