Lower Merion and Narberth Postcards

Contents

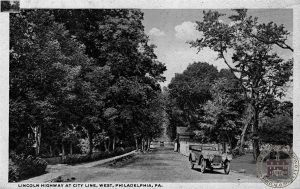

Chapter 1: Transportation — Rivers, Roads, Railroads and Trolleys

Chapter 1: Transportation — Rivers, Roads, Railroads and Trolleys Chapter 2: Inns, Restaurants and Hotels

Chapter 2: Inns, Restaurants and Hotels Chapter 3: Mill Creek’s Valley and Industries

Chapter 3: Mill Creek’s Valley and Industries Chapter 4: Business Communities and Services

Chapter 4: Business Communities and Services Chapter 5: Schools and Libraries

Chapter 5: Schools and Libraries Chapter 6: Houses of Worship

Chapter 6: Houses of Worship Chapter 7: Sports, Recreations and Parks

Chapter 7: Sports, Recreations and Parks Chapter 8: Residences, Neighborhoods and Streetscapes

Chapter 8: Residences, Neighborhoods and Streetscapes

Introduction

A Pennsylvania Railroad marketing piece persuasively described Lower Merion as follows: “…its atmosphere is pure: it is thoroughly drained by numerous streams: its soil is fertile; and it is in a striking degree picturesque. Nature — the great landscape gardener — has carved and molded it into rolling hills and placid vales, and so studded it with trees and interlaced it with crystal rivulets, that the picture everywhere is lovely to look upon.” Yet, surprisingly, in distance and in time, much of Lower Merion is closer to center city Philadelphia than many Philadelphia neighborhoods. This favorable location has been a major factor in the growth of Lower Merion as a premier suburban residential area. Indeed, in many ways, the story of Lower Merion can be viewed as a microcosm in which the processes of the industrial revolution and suburbanization in America played out.

For many, Lower Merion evokes an image of the prestigious “Main Line” with its large estates and castles. But there was another side to Lower Merion — equally important were its factories, mills, and industrial facilities, which spurred innovation and economic development. For over 200 years, Lower Merion was one of the region’s foremost agricultural and industrial powerhouses, and produced everything from paper and textiles, to railroad axles and lumber. Lower Merion and Narberth focuses on the era of the most intense development, between 1900 and 1950, when the character of each neighborhood was coming into its own. Each chapter is organized according to geography; we start with the furthest east site, and move west from one neighborhood to the next. We chose to focus on how the other 90% lived, so to speak — the history of the working class of the area — how they traveled, where they worked, what they did for fun, where they worshipped. It is easy for those of us who are lucky enough to live here now to forget about the simple histories of those who came before us, whose lives were spent traversing dirt roads, socializing at taverns, and filling their lungs with the soot expelled from railroad engines.

What many also don’t know is that the Philadelphia Main Line is also one of the most culturally rich regions in the country. First settled in 1682 by William Penn’s coterie of Welsh Quakers, the area has since undergone several transformations — from farmland, to industrial center, to the home of some of Philadelphia’s elite, to built-out suburb. Lower Merion and Narberth has been the set on which dramatic railroad rivalries were played out, while also witnesses the rise of the middle class.

A short history of the “Postcard”

There are many different kinds of history; we also decided to develop this book as the history of the area and the history of the postcard, told in parallel. Before the advent of the telephone, postcards and letters were the main means of communication, and over time, used as souvenirs. In 1898, the US Congress passed legislation to allow private firms to print cards — beginning the era of the “private mailing card.” Instead of government stamps on the front, photographs, engravings, and other images were used, giving them an added appeal. Up until 1907, it was not permitted by law to write anything but the address on the backs of these cards; personal messages had to be scrawled across the artwork. As a result, these cards are referred to as “undivided backs”, meaning they did not have a line going down the center of the back, a demarcation used later to separate the address from the personal message. Whether or not it has a divided back, in addition to where it is printed (most postcards up to 1915 were still printed in Germany, whose printing methods were the best in the world) are two of the easier ways to date a postcard to a specific time period. The turn of the century brought the first of the “real photo” postcards (i.e., postcards that were real photographs and printed on film stock paper), as well as the beginning of the divided back, harkening the beginning of the so-called “Golden Age” of postcards. It is said that the publishing of printed postcards during this time period doubled every six months, and that postcard collecting had become a national pastime.

In addition to the images, what we find to another intriguing piece of social history are the mundane, little snippets passed down from correspondents, now strangers to us — postcard messages. We have taken the liberty of incorporating some of the personal messages found on the backs and fronts of our postcards with descriptions of the local landmarks. Each in their own squirrelly handwriting and misspellings — sometimes added as a last minute annotation to the postcard image, others merely sending a well wish or a notice of comings and goings. It adds a verisimilitude to the images; even a fleeting connection to the buildings and people that no longer exist. And then there’s our personal favorite: a small line, confined to the corner of a postcard of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church — almost like it was meant to be whispered in one’s ear — unsigned, saying simply “Yes, dear. I know I’m handsome.”

Acknowledgements

On the evening of October 24, 1949, about 90 community residents showed up for the first meeting of the historical society-three times more than were expected. Their vision was to fill the gaps left by other community organizations and the local school system, which did not teach the stories of their surroundings, the heritage left at their doorsteps. Over 60 years later, we have not only stayed true to our mission but have also expanded it to include stewardship, outreach, and active conservation-in some cases, even revitalization-oflocallandmarks and open spaces. With almost 400 members and dozens of dedicated volunteers, we have been able to continually change in order to meet the needs of the community, which is ever-evolving.

If an organization such as ours were a building, our members and volunteers would be the mortar holding it all together. This book is dedicated to them. Special thanks to Ted Goldsborough, past president and friend to many; the employees and caretakers of West Laurel Hill Cemetery, who have continually proved themselves to be wonderful neighbors and assets to the community; the staffs of Lower Merion School District and Lower Merion Township, who have partnered with us in innumerable projects over the years; and Max Buten, who was instrumental in the preparation of the images for publication.

— Jerry and Sarah Francis

Unless otherwise noted, all images appear courtesy of the Lower Merion Historical Society and the Francis family.