| <-- Previous | LMHS Home | Contents | Order Book | Next --> |

Tish-Co-Han, an elder of the Toms River, New Jersey band (Lenópeh). His name may mean "He who never blackens himself." This 1735 portrait, by Swedish artist Gustavus Hesselius, shows him as a man of stout muscular frame, about 45 to 50 years old. In 1737, he signed the treaty known as the "Walking Purchase." The Penn family considered him "an honest, upright Indian."

The ancestors of the Lenape had hunted in eastern regions of North America for thousands of years, adapting through time to the changes in climate and landscape. By 1,200 A.D. these small and highly mobile bands had developed new strategies that gave them more efficient use of the land and its resources. Within a few hundred years they had formed into the several nations who met the Europeans after 1500. One of these bands called themselves Lenape (len-AH-puh).

What today we know as the Delaware River takes its English name from Sir Thomas West, Lord de la Warr, the first governor of the Virginia colony. To the Lenape, this river and the land around it was called Makeriskhickon and, in many ways, this always flowing river was the lifeblood of these people. In their own terms these people called themselves Lenape, meaning "the people."

The Europeans first referred to all of the Lenape bands along the western side of Makeriskhickon, as well as to two other nations whose territories touched the "Delaware" River, by the collective designation of "River Indians." All of these groups were later called "Delaware." They spoke a variety of Algonkian tongues, now collectively called the "Delawarean" languages.

"Delaware" Indian family (detail from a 1653 Swedish map). This drawing was produced in response to the curiosity that Europeans had about what American Indians looked like. The artist drew what he wanted to see, with the intent to advertise the New World, which resulted in this inaccurate picture of Lenape appearance.

At the time of the arrival of Europeans in the Middle Atlantic region, the Lenape people were organized into more than a dozen different bands, each with its own area for winter hunting, and its own summer station along the Delaware River. Most of the year was spent at these summer fishing stations. The individual band would "aggregate" into a social and economic unit for the warm months. Each individual family within the band would then "disperse" for winter hunting.

While these bands were somewhat flexible in membership, each tended to have a core group composed of closely related members. The young men in each band stayed within their birth band until they married, then would join the band of their wife.

The Lenape band living in the Lower Merion area was one of the largest of all. They traditionally summered in the rich swamps at the mouth of the Schuylkill, but hunted over the entire southwestern side of the Schuylkill River drainage which was their foraging territory.

The Lenape living in the resource rich area of southeastern Pennsylvania developed a sophisticated foraging lifestyle during the Late Woodland period (c. 1100-1600 A.D.). They hunted and fished and gathered many different kinds of plants, such as goose-foot and wild millet, in order to feed themselves. In the fall, hickory nuts and acorns were gathered and processed for food. Among the animals collected by Lenape women for food were bird eggs, nestlings, frogs, turtles and shellfish.

During the summer, everyone helped fish for shad, sturgeon, striped bass, eel, shad and many other water-dwelling creatures, using complex woven traps, large nets and harpoons. Lenape men also hunted in the surrounding forests for deer, elk, bear and birds, using the bow with arrows tipped with flat, triangular stone heads...finely chipped and very sharp. Other foods that now sound less inviting, such as caterpillars, also were important to the Lenape.

The Lenape lived simply; each band was made up of several related families who worked and ate together. The members of any band could marry into any other band within the Lenape area, and rarely did they marry someone who was not a Lenape.

In 1985, excavations undertaken for the University Museum in Philadelphia located evidence of some small structures of the kind described by William Penn, who provided most of the direct descriptions of Lenape constructions:

"Their Houses are Mats, or Bark of Trees set on Poles, in the fashion of an English Barn, but out of the power of the Winds, for they are hardly higher than a man..."

Contemporary artwork depicts Lenape contact with new European arrivals and their neighbors to the west, the Susquehannock.

The arrival of Europeans provided the Lenape with a new set of opportunities. Dutch traders from Fort Amsterdam, located on the North (Hudson) River, came down to what they called the South River in 1623 specifically to trade with the Susquehannock. Those people, the most powerful native nation in Pennsylvania, brought furs overland to the Delaware River to avoid the renewed conflicts between the Powhatan Confederacy and the English colonists on the Chesapeake River.

The Dutch put up a tiny trading post, Fort Nassau, on the Jersey side of the river opposite the mouth of a river they called the "Hidden Stream" ("schuylkil" in Dutch). The swamps and islands at the mouth of the Schuylkill made it difficult for early sailors to identify the true course of this river, so well-known and easily traveled by the Lenape.

The people of the South Schuylkill band became important figures in the quests of these various European traders for "legitimacy" as regards trading rights and land claims. Until the Swedes arrived in 1638 and bought land at Hopokehocking (now Wilmington) from the Brandywine band, the Schuylkil River people were the best known of the Lenape bands.

The Dutch came to "their" South River primarily to trade with the Susquehannock, but did not set up a permanent fort or individual homesteads. Before their Swedish competition arrived, there was little concern with land claims and territorial rights.

Aerial view of the Schuylkill River in Gladwyne where there is a bend in the river. At this location, due to the water’s change in direction, there is a natural pool of warm water where fish congregate. This is where the Lenape set up their "summer station" to trap fish, which was a staple in their diet.

The Swedish colony was established principally to trade for furs, but failed to make a serious dent in the Dutch fur market. Taking a lesson from the Virginia Company, the Swedes went into the production of tobacco. The expansion of Swedish farmsteads and their continuing efforts to crack the Dutch fur monopoly, led to an interesting contention between the Swedes and the Dutch over land rights.

To counter the Swedish expansion into the Schuylkill Valley, the Dutch bought a few acres from the Lenape and built a small fort called "Bevers Rede" on the west banks of the Delaware. These deeds provide us with clues to the membership and territory controlled by the dominant Schuylkill River bands of Lenape.

The turtle was part of the Lenape story of creation. As the story goes, Kishelemukong, the Creator, brought a giant turtle from the depths of the great ocean. The turtle grew until it became the vast island now known as North America. The first woman and man sprouted from a tree that grew upon the turtle’s back. Kishelemukong then created the heaven, the sun, the moon, all animals and plants, and the four directions that governed the seasons.

During the period following the Swedish entry into the South River (c. 1638-1660), the local Lenape had slight profits from the European competition for furs. The Lenape and their immediate neighbors had only the furs that they hunted from their own territories to trade; the Susquehannock were middlemen in the fur trade that extended out into the Mississippi Valley. Thus the Lenape were, as Swedish Governor Printz put it, "poor in furs." These sales provided the Lenape with one means of access to highly valued trade items such as metal goods and blankets.

A second source of European goods derived from the sale of maize to the Swedes. The Lenape had always grown a bit of maize in their summer gardens, but after 1640 they increased the amount planted to sell to the Swedish colonists. The Swedes were concentrating their planting on tobacco for export, and bought maize from these Lenape foragers at lower costs than the value of tobacco. In this way the Lenape gained trade goods while not having to deal with the problem of food storage.

In addition, the Swedes provided a new and useful means by which the Lenape could make it through particularly bad winters. If the hunting was bad, Lenape families could rely on the Swedes for supplementary rations during the "starving time."

Another Lenape technique for gaining access to European goods involved the sale of land. In general, the plots sold were small holdings and the goods received were considerable. Lands sold to one group could often be promised or "sold" to another group at a later date.

At a major gathering in 1654, six members of the North Schuylkill band were joined by two Lenape from the South Schuylkill band and two other Lenape from a third band. This gathering led to a major land sale. The North Schuylkill band sold a huge portion of the lower part of their territory, excepting "Passaijungh," where they continued to spend the warm months doing their traditional fishing.

Black rocks, different from other rock formations in the area, cover some four to five acres near Mill Creek as it passes under Black Rock Road in Gladwyne. Geologists say the nature of the rock represents gradations from serpertine to talc. Tradition holds that the Lenape camped in the area because it was the source of chert, a flint-like stone used in the manufacture of spearpoints and arrowheads.

The lands that became Pennsylvania came as a Crown grant to William Penn. Penn believed that the wholesale purchase of land from its native owners, and the subsequent division and resale of small plots, would make him fabulously wealthy. By the time Penn received his grant and developed his plans for what became "Pennsylvania," thousands of English colonists already had come into the area.

This increase in population, most of whom purchased small tracts of land along the Delaware River, began to influence native fishing and foraging strategies by the 1660s. Rather than sustaining their summer fishing stations directly on the Delaware, individual Lenape bands began to shift their summer stations further up their respective streams. From c. 1660 to 1680 the Schuylkill River and other other bands were also relocating their summer stations further up river, with the South Schuylkill band shifting to a location in the Lower Merion area.

Between 1682 and 1701, Penn patiently negotiated the purchase of all of the holdings of every one of the Lenape bands, except those areas on which the individual bands "were seated" (had their summer stations). The first of these deeds were drawn up in July 1682 by William Markham, Penn’s agent, shortly before Penn himself arrived in the New World. The deed that is of most interest concerns the sale to Penn of all of the lands claimed by the South Schuylkill band (what is now Montgomery County).

The following July, two different Lenape bands came to negotiate sales of their lands to Penn for an incredibly rich array of trade goods. The first of these sales was made by the band living west of the Schuylkill. They sold all the land lying between "Manaiunk alias Schulkill" and Macopanackhan (Upland or Chester) Creek. This sale included land only up as far as the hill called Conshohockan.

These sales did little to change Lenape life ways other than to provide them with a vast quantity of useful goods. From the list of goods that Penn used to "buy" this tract, we can estimate the band size: 30 adults and possibly an equal number of children, since the goods involve items in multiples of 15. For the men, there are 15 guns, knives, axes, coats and shirts plus 30 bars of lead. For women, there are 15 small kettles, scissors and combs, but 16 pairs of stockings and blankets.

Lenape Artifacts

Archaic period spear head

Full-grooved, pecked, cobblestone axe head, c.8000 BC to 4000 BC

Sway-backed knife, c. 10,000 BC to 8000 BC

Bannerstone/Atlatl weight, c.4000 BC to 1000 BC

Jasper (a variety of quartz) point and scraper

Knife point (handle added) c. 1000 BC to 1550 AD

Pecked & polished chisel, c.8000 BC to 4000 BC

Dart heads or knives

Antler harpoon

Gorget (soapstone) pictograph, c. 1000 BC to 700 AD

Chopper/hoe blade c. 1000 BC to 700 AD

Pitted stone, 8000 BC to 4000 BC

All of the Lenape bands continued to live in the Delaware Valley for another 50 years, but at locations further up the streams. They lived in much the same way that they had for centuries before...and continued to reside in these areas for another 50 years.

Only in the 1730s was the density of the English settlement and the subtle influences it had on native life-ways, considered a potential problem to the Lenape. Many were marrying or settling among the colonists and the traditional modes of living were becoming difficult to follow in the lower Delaware Valley.

Between 1733 and 1740, all of the conservative members of many Lenape bands had decided that economic opportunities and the chance to maintain the old ways lay in moving west. In leaving the coastal plain, these Lenape set the pattern that would be followed by early colonists and other immigrant groups to follow...moving west for opportunities that lay beyond the Atlantic shore.

Lenape had been moving west since at least 1661. When William Penn arrived, many Lenape already had left the Delaware Valley and others were ready to sell their lands and move out to central Pennsylvania and beyond. Most of the conservative and traditional Lenape people had left the Delaware Valley by 1740.

The numbers of Lenape who simply merged into the colonial society explains some "disappearances" of many aboriginal groups. For the Lenape, the attraction of wealth to be gained from the fur trade pulled many people west more forcefully than they were being pushed west by colonial population expansion. These Lenape people have joined with many other peoples to become the foundation for modern American society.

Far and away the best pioneers and precursors of Penn’s Holy Experiment were the Swedes and their then compatriots the Finns, who, as Penn observed, were settlers, not mere traders. The Dutch laid claim to the Delaware Bay region via Henry Hudson’s explorations in 1609, but their desultory stabs into the wilderness to trade with the Indians for furs left little of permanence. Their early town Swanendael at the site of Lewes, Delaware, lasted about one year, was burned and the residents killed by Indians.

Until free-standing cabins could be built, newly arrived settlers dug into the river banks and cut saplings to reinforce walls and improvised roofs with branches, thus creating decent shelters that lasted for years.

Peter Minuit lost his job running New Amsterdam up on the "North River" (the Hudson..."South River" was the Delaware) and was ordered home by the Dutch West India Company, whereupon the Swedish government hired him to lead an expedition to Delaware Bay. This venture resulted in founding, in 1638, New Sweden based at Fort Christina near present day Wilmington.

The farmers of New Sweden, some fleeing the uproar of the Thirty Years War, and unlike the volatile Dutch of New Netherland (where shouting matches were the norm), built their log cabins, were friendly toward Indians and prepared a solid foundation for the sort of society William Penn had in mind.

Swedish governor John Printz negotiated with local natives to claim all the western shore of the Delaware from Cape Henlopen to the Falls of Sanhickan (Trenton), and Scandinavians spread north into small farms and settlements at Upland (Chester), Wicaco (now part of Philadelphia) and Kingsessing ("a place where there is a meadow") between Cobbs Creek and the Schuylkill.

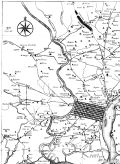

Scull & Heap map of Philadelphia and environs by George Heap (c. 1715-1752), He drew "An East Prospect of the City of Philadelphia," engraved by George Vandergucht. Nicholas Scull (1687-1761) was Surveyor General of the Province of Pennsylvania.

But all this bucolic peace was terminated by two major events: Peter Stuyvesant (whose name translated means "stir up sand") stormed down from Man-a-hatta to chase out the interlopers of New Sweden in 1655, thus igniting skirmishes between Dutch and Swedes for the next nine years,

Then, in 1664, a second military adventure had an impact that ended all arguments once and for all: the British navy arrived. John and Sebastian Cabots’ exploration of 1497 planted in the British mind the notion that North America belonged to them and, by St. George, they intended to keep it, though lenience had prevailed almost 200 years.

Far from flinging out the foreign residents, the British encouraged existing settlers to stay, indeed gave them extra land in some cases.

Of the 2000 Europeans living in the area (fifty families within the modern limits of Philadelphia), almost half were Swedish/Finnish folk. So it was that, to begin the Holy Experiment and build a city on the Delaware River, Penn’s commissioners had to purchase about a mile of waterfront, high firm ground (between today’s South and Vine Streets) from owners Sven, Olaf and Andrew, sons of Sven Gunnasson.

Just about everybody knows that Quaker William Penn was given Pennsylvania in 1681 by the King of England to pay a debt owed to his late father, Sir William Penn (Admiral of the British Navy) who fought for the crown and was a particular friend of the royal Stuarts. Curiously, young William (though considered a religious renegade and often in jail) remained on good terms with his king and the Duke of York (the king’s brother, who owned, but relinquished, the land to pay the debt). But not many know that in 1675, six years earlier, the younger Penn, without leaving England, had helped to settle an argument between two Quaker landowners in West New Jersey. This provided him the opportunity to foreshadow things to come when he wrote a liberal frame of government, "Concessions and Agreements of the Proprietors, Freeholders and Inhabitants of West Jersey in America," emphasizing freedom of conscience and planting seeds of a new order...the Novus ordo seclorum...from which we benefit and acknowledge every time we salute the flag and the republic with "liberty and justice for all."

Benjamin West, Penn’s Treaty with the Indians (1771-72), Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia.

As he received reports from New Jersey so Penn learned about the Delaware Valley, how rich the soil, how well-wooded the countryside, how plentiful the game and fish. George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends (Quakers) had traveled from Maryland to Long Island in 1672, dreaming all the while of a refuge for his beleaguered followers. As early as 1661, Parliament passed an act labeling Quakers with their uncomfortable penchant for speaking truth to power, as "dangerous and mischievous," and real persecution of Friends began.

Consequently, when William Penn petitioned the king for the grant of land that turned out to be almost as big as England, it was at least partly to be a refuge for the persecuted. In 1681 the Great Charter, boldly inscribed on pages of large parchment today in Pennsylvania’s state archives and displayed on Charter Day (March 4), gave into Penn’s hands what he intended to name "New Wales," but the king’s secretary called "Pennsylvania" to honor his father.

Penn also advertised his American lands widely on the Continent and throughout Britain and caught the attention of merchants, farmers, artisans, educated gentlemen intrigued by "liberty of conscience," as well as those simply seeking wealth, who together created a colony that became a seedbed for a new nation one hundred years in the future.

Did you ever hear a newcomer to our Township try to pronounce "Cynwyd" for the first time? Or "Pencoyd"? Or spell "Bryn Mawr" correctly? We’re dealing here with remnants of a very old language that came to rest in the New World with hardworking folk from Wales, descendants of the ancient Britons, the Cymric Celts. These Welsh members of the Society of Friends began to arrive on our ground in 1682 to escape harassment for being Quakers – confiscation of property, fines, sentences to jails of horrible reputation. Friends refused tithes, oaths and worldly courtesies and practiced a plain and direct form of meditative worship for which church and lay officials caused them no end of trouble.

Not long after the Great Charter was delivered to William Penn, a company of seventeen Quaker families in Merionethshire, North Wales, sent two representatives to buy 5000 acres in America for 100 pounds. Seven such companies from various parts of Wales accounted for 30,000 acres, plus individual purchases. Acreage would be "sett out as...appointed as neare as may be Land of equall goodness with the rest, or as shall out by Lott."

But there was a flaw in the arrangements. A select group of those First Purchasers met with the Proprietor and were assured, on response to their request, that their land would be surveyed in contiguous acreage so that they might speak their own language and be governed (or at least judged) by persons they would elect, and thus form a "Barony." Indeed, the Proprietor required of Thomas Holmes in 1684: "...to lay out ye sd tract of Land in as uniform a manner as conveniently may be, upon ye west side of Skoolkill river, running three miles upon ye same & two miles backward, & then extend ye parallel wth ye river six miles, and to run westwardly so far as this ye sd quantity of land be Compleately surveyed...Given at Pennsbury, ye 13th 1st mo. 1684."

But there was nothing written to prove and bind the agreement. Part of the land purchased turned out to be in distant Goshen, even in New Castle and Kent counties (now Delaware). Furthermore, several tracts of land in Haverford, Radnor and Merion were assigned English purchasers and some Swedes, all within the hoped-for Barony.

Political animosities arose: Haverford and Radnor townships were declared to be in Chester County (now Delaware County); Merion Township remained in Philadelphia. Despite petitions and protests, hope of a Barony...a County Palatinate...was abandoned.

Three Welsh Quaker meetings remained in close association and built meetinghouses: Old Haverford Meeting on Eagle Road, Havertown; Radnor Meeting at Sproul and Conestoga Roads; and Merion Meeting at Meetinghouse Lane and Montgomery Avenue.

These three formed a "Monthly Meeting" to handle disputes, estates, legacies, applications to marry, care of hard luck cases, reprimands, acknowledge fulfillment of indentured servitude, or hear grievances of servants against their employers. These business meetings met on rotation among the three meetinghouses. As the amount of business increased, the Monthly Meeting created the "Preparative Meeting" to filter some of the items. Merion Meeting was, until the mid 20th century, called a Preparative Meeting, one that would prepare reports to present to the Monthly Meeting. Today, these three meetings are independent, but are loosely joined via Quarterly Meeting and the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting.

| <-- Previous | LMHS Home | Contents | Order Book | Next --> |