Narberth

By Victoria Donahoe

Montgomery County: The Second Hundred Years, Chapter 33

Edited by Jean B. Toll and Michael J. Schwager

Published by The Montgomery County Federation of Historical Societies (Norristown, 1983)

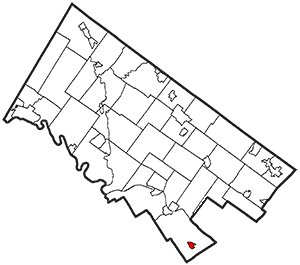

1980 Area: 0.52 square mile

Established: 1895

Before becoming a borough in 1895, Narberth was not one village but six successive settlements—Indian, Swedish, Welsh, the hamlet of Libertyville, the nucleus of a “Godey’s Lady’s Book town” called Elm, and three simultaneous tract-house developments: Narberth Park, the south-side tract, and Belmar. Narberth Park Association, called after the tract development of that name and begun by fifteen of its residents, originated on October 9, 1889. This organization seemingly started just to provide simple community services on the north side of Elm Station like those a tract on the station’s south side already enjoyed. It proved to be a political beginning for the present borough.

Achieving Independent Rule

Activities of the Narberth Park Association have often been described. There were committees for public safety, public works, ways and means, and membership. Ash collecting began at $1.25 per week; garbage collecting was free. The association purchased a bell and placed it on Forrest Avenue as a fire alarm, bought fire extinguishers, distributed all-purpose alarm whistles to members, and offered a two-hundred-dollar reward for the capture and conviction of burglars. By the end of 1890 “Park” was dropped from the association’s name.

The Narberth Association in 1891 installed sixty oil lamps on the Narberth Park tract of developer S. Almira Vance at the residents’ expense. It furnished oil, and a lamplighter earned $7.50 a month. By spring of 1893, the Bala and Merion Electric Company had installed electric street lighting on the tract, featuring twenty-four lights of sixteen candlepower each. Narberth Park still had just forty-five houses, and Narberth Avenue was the only macadamized street. Pavements were of wood. There were no connecting drains or sewer system, and no police.

| POPULATION | Number | Rank |

|---|---|---|

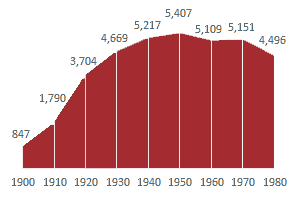

| Total Number | 4,496 | 39 |

| White | 4,419 | – |

| Non-White | 77 | – |

| Density (persons/sq. mile) | 8,646.1 | 3 |

| Median Age | 33.7 | 14 |

| Median Family Income | $23,997 | 31 |

| HOUSING | ||

| Total Number | 1,948 | 35 |

| Persons per Household | 2.3 | – |

| Median Value | $60,900 | 24 |

Local residents no longer had to depend on the post office at General Wayne Inn. Another, to be called Elm, had been sought and denied because of a name conflict with an existing facility. However, in 1886 a Narberth post office was approved. It was located in the railroad station, which itself underwent a name change from Elm to Narberth in 1892. The Narberth designation won approval from Pennsylvania Railroad president George Brooke Roberts, in what must have seemed by then an obvious choice of name. These rail and postal facilities served the tract houses on both the north and south sides of the railroad.

A Public Ledger account of November 13, 1890, was correct about Elm and nearby communities: “All along the line of the Pennsylvania Railroad, for several miles outside Philadelphia, are indications of remarkable growth and a very healthful condition of matters in the real estate line.” Development spread over a large area of Lower Merion Township, but public improvements crept at a snail’s pace. The residents’ association of Narberth Park set out to speed up the delivery of needed services. In June 1893 it formed a committee, comprising A. H. Mueller, Sylvester J. Baker, Charles E. Kreamer, David J. Hunter, and Edgar A. M. L’Etang, “to look into the advisability of obtaining a Borough Charter.” The chief attraction of independent rule was that it would have powers to establish public improvements not then being attained under the supervisors’ rule of Lower Merion Township.

The same residents group in October 1893 petitioned Montgomery County courts to incorporate Narberth as a borough. Proposed boundaries were to be the center lines of Wynnewood Avenue at the railroad tunnel to Montgomery Avenue, along it to Merion Road, along Merion Road to Bowman, to the railroad tracks, along these to Wynnewood Avenue. They acted only on their own behalf. Having no connection at all with the separately run “south side” or its water supply and drainage systems, they excluded the south side from their proposal. The borough’s Fiftieth Anniversary Report (1945) says that opposition to creating a borough was voiced by owners of large property and the railroad, among others, who saw no benefit. Not surprisingly, Judge Aaron S. Swartz ruled against the borough charter the first time around. His decision indicated that the Act of Assembly dealt with incorporation of a whole community, not just one part of it. It became clear that the judge considered the south side essential to the Narberth community.

In June 1894 a larger group of citizens returned to court with a new petition adding the specification that the south side as far south as Rockland should be incorporated as Narberth. In it they declared there were 129 property owners. Of some 78 resident freeholders, 47 were recorded in favor and had signed the petition, one remaining neutral. Some 38 nonresident freeholders signed the petition, as well as about 70 voters out of a total of about 120. Each of the various categories had a majority in favor, one of the petitioners, A. H. Mueller, stated.

This second appeal to court was successful. In the report of the county grand jury, a majority of at least twelve of its members approved it.

When Judge Swartz finally confirmed the grand jury’s finding on January 21, 1895, he fixed Narberth boundaries somewhat different from those proposed. Because it was exclusively farmland and had no building lots yet laid out in it, he sliced off and excluded a 61.5-acre section southward from Haverford Avenue extending from Narberth Avenue to Montgomery Avenue and Merion Road, and as far as the railroad track, letting this remain as Merion. At the same time, in accord with the court’s decree, the judge set the date for the first borough election as the third Tuesday in February 1895.

Completely surrounded by Lower Merion, the new borough occupied 0.52 square mile, and its boundaries are the same today. It is the only community in Lower Merion Township ever to sever ties with the parent township. It accomplished this when efforts to attain boroughhood were at a fever-high pitch, shortly after Ardmore and Bryn Mawr in the same township had held public meetings about taking a similar step and voted against it. And it was shortly before the adoption of a township classification law at the turn of the century that gave townships new powers, something of which Lower Merion rapidly took advantage. Passage of this law has since cooled the fervor of communities seeking borough status.

In 1936 there was a court hearing for a hotly contested petition to recall Narberth’s borough incorporation, but the petition was withdrawn when the evidence seemed to show that some people had signed more than one name. A citizens’ group calling itself Victory Committee for Home Rule for Narberth went home happy that day.

Emblazoned on the center of Narberth’s corporate seal is an elm tree, the symbol of the village, all of which (north and south of the railroad track included) at one time was called Elm.

One month after the creation of the new borough of Narberth, on the third Tuesday in February 1895, north- and south-side citizens went to the polls and elected their first borough officers. Lithographer August H. Mueller became the first burgess. Elected councilmen were Sylvester J. Baker, F. Millwood Justice, Alfred A. Lowry, James C. Simpson, and Richard H. Wallace from the north side, and Jacob M. March from the south side.

Wallace, an insurance agent and broker, was elected council president, and A. Perry Redifer, a manufacturer of lasts, was named clerk at the first borough council meeting on March 4. The first item of business was to set a tax rate of five mills, expected to produce an $18,572 revenue from $371,450 in assessed property valuation. Taxable properties totaled 151. One of the earliest ordinances tried to limit the unrestricted wandering of horses and cattle within the borough. Another specified that only persons who already had pigs in their possession were allowed to keep them. Other achievements the first year included founding a Board of Health, building (by Goodman and Clothier) a Windsor Avenue sewer with lateral connections at all cross streets, and macadamizing some streets. By December 1895 assessed property value rose dramatically to $636,600, and a $12,500 bond issue authorized public improvements.

Early Settlement

Narberth, full of springs, may have been first a Lenni-Lenape Indian village and a place where Indian councils were held. So far this is supported only by anthropologist Marshall Becker’s general assertion that the early Friends built meetinghouses and the Swedes built log cabins where there had been an Indian settlement because of the convenience of using land already cleared and the assurance of a fresh water supply.

Also believed to have been located here was one of the oldest colonial settlements in the county, a Swedish trading post site with the warlike Conestoga (Susquehannock) Indians. Some evidence suggests that Swedish people still lived here when the Merion Welsh came two months before William Penn in August 1682, and that a few of them may have asserted their right to remain on a corner of at least one Welsh plantation in Narberth. (See writer’s article on Swedish findings in the Bulletin of the Historical Society of Montgomery County, fall 1982.)

Narberth farmland, wet meadow, and woods were at the heart of the Merion Welsh tract. Three of the most prominent of the original seventeen families who settled this tract in search of religious freedom in 1682, and a fourth arriving in 1683, owned land granted to them by William Penn in what is now Narberth Borough, a fifth arrival making it a quintet of Welsh family owners within a decade.

Edward ap Rees’s original seventy-eight acres here (the other half of his grant was in West Chester) was the centerpiece of the parcel featuring his stone house (1690) at the southeast corner of Windsor and Forrest avenues. Merion Friends Meeting was also built on Rees’s land, trimmed and given from the far northeast end of his tract just outside the present borough. Portions of larger tracts owned by the other Merion Welsh pioneers extended into Narberth to frame Rees’s land.

Surprisingly, Narberth’s Welsh property line boundaries have remained largely intact, so the line (made about 1683) marking the original western edge of the 2,500-acre Merion Welsh tract is discernible where it passes north and south through the borough’s west end. Described as the “Merion Line” in two separate Narberth deeds for the year 1691, those of Robert Owen and Edward ap Rees (Deed Book E2 volume 5, pp. 174-75, City Archives of Philadelphia), that ancient boundary runs parallel with North Wynnewood Avenue some 350 feet east of it. Today the old Merion Line can be easily traveled within the borough along a hilly two-block straight stretch, the western service drive of Narbrook Park, entered from Windsor Avenue with Indian Creek to the right.

After the Merion Welsh settled Narberth’s land east of the Merion Line in 1682, the line’s western boundary indicated a virtual frontier zone between the Merion and Haverford tracts for several years. In Narberth, no land west of the Merion Line was settled until 1691, when Robert Owen, fleeing persecution, and Edward ap Rees, beginning to enlarge his farm, each bought from the original deed-holders large tracts extending into that zone. The woodsy appearance of Narberth’s west end even today is a reminder that this section of land came under Welsh cultivation later than the rest of the borough. The slender slice of borough land fronting on North Wynnewood Avenue now goes by the name of “Narberth’s gold coast,” and not because it faces the setting sun.

Carden F. Warner (Narberth’s Historical Prelude, 1616-1895, 1905) says that Revolutionary (or pre-Revolutionary) Narberth turf served as a public rallying place for patriots when a Liberty Pole was set up here by French soldiers on the old trading post site. The village of Libertyville sprang up at that location by 1834, when it became a stop on the old Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad. A more likely explanation for the origin of its name is the nearness of the area to Gladwyne, where a Liberty Pole was raised in 1799.

The name Libertyville existed until Narberth Borough was incorporated, but before 1895 the use of the term “Elm Station” began to eclipse that of Libertyville as an address covering a wider area and including Fairview (Penn Valley).

Narberth had a “witch” named Betty Conrad, mentioned as such on January 23, 1806, in Major Joseph Price’s diary (Historical Society of Pennsylvania manuscript). In her will proved that year she subdivided her 6¾-acre farm among her four children so that each had a lot facing Montgomery Avenue. Mrs. Conrad’s property with buildings on it, and at least two other nearby (log) houses enclosed in houses at 1226 Montgomery and 610 Shady Lane and probably Swedish, were the nucleus of Libertyville. Razed by a real estate speculator in June 1980 at 1292 Montgomery Avenue was a wooden house, almost certainly the “witch’s.” Her children’s curbside houses at 1296, 1294, 1268, and 1256 Montgomery remain, but the rest of the “witch’s” tract is a subdivision of French provincial-style houses, built in 1980, which has wiped out much of Libertyville’s character by destroying the ancient Indian Creek spring house, an early orchard, the Connor family’s barn-slaughterhouse, and Super’s blacksmith shop. A hub of activity in this farming area, the Connor and Super businesses flourished at Libertyville from the Civil War until the early twentieth century. Most old-timers still remember the large Super family at 1256, whose blacksmith shop outlasted the other smithy in Narberth, located since colonial times opposite General Wayne Inn.

Descendants of various branches of the Price family owned the assembled Price colonial landholdings until 1838, when the southern half of the original (1682) ap Rees or Price tract was sold for $5,650 to farmer William Thomas of Blockley Township, who had emigrated from Wales in 1818. Thomas’s sixty-two-acre purchase, not all of it in the present borough, was bounded on the north by the then Haverford-and-Merion Road, and his homestead was at the Montgomery Avenue end.

When the West Philadelphia Railroad Company was planned along the route that became the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Main Line now operated by Amtrak and Conrail, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania paid William Thomas for 2.747 acres in 1851 as a right of way for the tracks. This was to be a better route than the old Columbia Railroad’s inclined plane in the present West Fairmount Park. The Pennsylvania Railroad main line takes a wide-arc turn just before reaching Narberth, a necessity to avoid some sharp rises in the ground in Wynnewood. So that the puny locomotives could make the grade to Ardmore, the tracks followed the stream beds. The entry into Narberth was a twisting and scanning perspective, a reminder that Narberth developed as a passage or gateway to somewhere else.

William Thomas set in motion a process that would result in the building of a railroad station on his property. According to mid-nineteenth-century thinking, building a railroad station was the catalyst necessary to create a town. Doubtless Thomas shared that outlook. However, there is no evidence that Thomas later sold off lots of two acres or more to encourage building of that town, as many accounts have stated. That distinction belongs to Edward R. Price, the “last of the Prices,” and to him alone.

At age eighty-one, William Thomas and his wife Sarah sold three-quarters of an acre to the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1869 for one dollar “provided the lot be used solely and entirely” to build a railroad station. According to one account this donation was made with the understanding that the station should always bear the name “Elm” for Thomas’s old home in Wales or, according to another, because the many elm trees on his plantation were a constant reminder of his Welsh birthplace. William Thomas supposedly came from southern Wales.

A Swiss chalet-style railroad station was built of stone north of the tracks in 1870, and called Elm. After Thomas released an enlarged right of way to the Pennsylvania Railroad, it built the Wynnewood Avenue underpass on his former turf in 1879. The previous year, East Wynnewood Road had been established by court order. North Wynnewood Avenue had existed since 1865.

J. W. Townsend, in his Main Line reminiscences, mentioned that railroad brakemen used to pronounce the station’s name “El-lm.” With a note of sarcasm, local residents, maneuvering around many mud puddles, took to calling the area “Slippery Elm.”

Notoriety came to Elm in 1876, when a German immigrant was murdered near the station; citizens and officials raised a thousand dollars to bring the guilty party to justice.

South of the Thomas tract was the former plantation of Dr. Edward Jones (Dr. Thomas Wynne’s son-in-law), who spoke about the Indians leaving venison at his door “for six pence ye quarter.” That land passed in turn to his son Jonathan Jones, Anthony Tunis, Joseph Tunis, John Dickinson (eminent scholar of the Revolution), Jacob Morris, and James Sullivan. In 1863 Charles S. Wood, president of Cambria Iron Company, which made railroad iron at Johnstown, bought from farmer Sullivan the tidy slice of this land that now forms the southernmost portion of the borough, calling it Rockland Farm. Wood kept twelve Alderney cows, a Dearborn wagon, brown and sorrel horses, and a bay mare at that farm, marked “C. S. Wood Estate” on the official 1895 borough map.

The south-side story becomes dormant until 1888, and the scene shifts north of the tracks. The upper half of the original (1682) Price tract remained in family hands until a Philadelphia restaurant owner, widow Maria Furey, bought it in 1871. Carden Warner gives a good account of that plantation prior to 1871. Mrs. Furey farmed the land profitably. She turned the large Price house (1770) near present-day Windsor and Narberth avenues into a boarding home.

Maria Furey distributed to her daughters Martha (Mrs. Marmaduke S. Moore) and Mary (Mrs. Joseph Mullineaux, Jr.) a few acres, where they built adjoining houses at 417 and 413 Haverford Avenue. Mrs. Furey seemed to be marking time.

Just north of her property, change was in the air. The “last of the Prices” to own ancestral lands (a hundred acres) here, aging Edward R. Price, lived in the house his grandfather Reese Price built in 1803 at 714 Montgomery Avenue, and was about to embark on the most ambitious scheme of his life.

“Lady’s Book Village” at Elm

Under the impetus of a growing moneyed class and the increasing demand for summer houses on Philadelphia’s Main Line, Edward R. Price commissioned a plan (1881) for a “Godey’s Lady’s Book village” at Elm with its main street on what is now Narberth Avenue. On April 18, 1881, he sold four large adjoining lots to carefully selected customers: five acres to Samuel Richards, two lots (six and three acres) to architect Isaac H. Hobbs in one of the rare instances of real estate ownership by him, and ten acres to his builder. Hobbs had long enjoyed a reputation as “Godey’s favorite architect.” The only American mass circulation monthly magazine of its day that regularly published house designs specially done for it, Godey’s Lady’s Book popularized domestic architecture for the middle class, an unprecedented thing. Hundreds of houses from Hobbs’s published designs were built singly or in groups in the eastern part of the country. Several Lady’s Book houses became a Lady’s Book village.

The only identified Lady’s Book house still standing in Narberth is Barrie House, a Methodist parsonage on Price Avenue. There may be others not yet identified. Despite differences in style, the houses Hobbs built in 1881-84 on these lots, some adjacent houses, and three other big ones in the heart of Libertyville, all built by 1890, shared fundamental elements that reflect the energy of the period. These elements were on the one hand a desire to break away from the agricultural traditions of the neighborhood, and on the other, imbalance and surprise.

Initially opposed to selling off any of his own acreage for the development, Price came around to the idea soon after whiskey merchant Henry C. Gibson started building a mansion in Wynnewood on former Price land. Price chose as its first resident a leading representative of the closest thing this country had to a landed aristocracy. He invited Samuel Richards, a scion of a family that earlier had land-holdings of more than a quarter of a million acres including New Jersey’s Wharton tract.

Did Samuel Richards convince Edward R. Price to start a village here? Did he help Price overcome his earlier objections, saying that he would gladly come and live here himself? That is probably close to the truth. Richards was a man to be listened to in such matters. Always interested in a place with a future, he became in 1881 the key resident of Elm village.

Fifteen years earlier Richards had founded the full-size town of Atco, New Jersey, seizing an opportunity provided by a new railroad junction. He named the streets in alphabetical order, except the main avenue, which he named after the town.

The hard-driving and energetic Samuel Richards was already credited with launching the idea of a string of southern New Jersey seashore resorts, the physical development from scratch of those communities, the naming of one of them (Atlantic City), and the building of “the railroad to nowhere,” which served Atlantic City with astonishing success. (See Arthur D. Pierce’s Family Empire in Jersey Iron: The Richards Enterprises in the Pine Barrens, 1964.) As the excitement of his own ventures began to subside, Richards looked for a place to live near Philadelphia with his wife Elizabeth Moore Ellison and his second son and business partner, the low-keyed S. Bartram Richards, and Bartram’s bride Mary Dorrance Evans (remembered as “Aunt Mary” by John T. Dorrance). Isabel Bishop, the distinguished painter, is Samuel Richards’s grandniece.

Another advantage the Richardses had, in Price’s eyes, was their flawless Quaker credentials, especially those of Mrs. Elizabeth Richards. Her father, John B. Ellison, a textile industry leader, was a staunch Friend. Her aunt and namesake, Elizabeth Ellison, was a celebrated Quaker preacher. The presence of the Richardses provided Price with the best possible “sales pitch” for his village.

The project at Elm was the golden dream of three men in their golden years—farmer Price, architect Isaac Harding Hobbs, Jr., and Samuel Richards. Of these, the Richardses retained some of their land the longest, nearly forty years.

The site selected for the planned village of Elm, crowning the center of Edward R. Price’s hundred-acre farm, was excellent. Picturesqueness and variety distinguished this hamlet of Hobbs-designed homes. His largest local mansion (razed for Montgomery Court Apartments) and another Hobbs dwelling (the Barrie House parsonage) stood together on a high broad shoulder of land on Hobbs’s own nine acres that sliced across a bluff to Indian Creek. Barrie House is rugged and reflects Hobbs’s sense of power over massive structures and over its sometimes mildly extravagant French Second Empire ornamentation. This house, enhanced now by the cheerfulness and grace of an enormous white birch that shades the entrance, faces Price Avenue, but its balcony and picture window overlook the length of that lot to acknowledge what must have been a romantic view westward.

Barrie House is the last leaf in the first round of Narberth town planning presided over by Edward R. Price. Since it was built speculatively, it provides unique testimony to the kind of newcomers sought for this community in 1881. In putting up new buildings, Victorians sought satisfaction, not from beauty, but from attaining what would befit the station in life of prospective buyers. Thus it might have gratified Price and Hobbs to know that two men of achievement, both medal winners at the Paris International Exposition of 1900, lived in Barrie House in succession—Samuel Vauclain cited for locomotive design and George Barrie for publishing deluxe editions of the classics.

Samuel Vauclain, the legendary head of the Baldwin Locomotive Works, was Narberth’s first industrial giant. In many ways he was far ahead of his time, promoting national and local prosperity as well as an improved market for American goods. Vauclain was the guest-resident of this house from 1885 to 1901, courtesy of its owner, brass manufacturer T. Broom Belfield, a close friend and admirer who lived in the adjoining Hobbs mansion. While Belfield owned these properties, what became Barrie House was exclusively for Vauclain use, Belfield’s daughter-in-law, Mrs. Percy C. Belfield, declared. Though residing in a Green Street townhouse in the city, Samuel Vauclain believed in country living and fresh air for his young family.

Scotch-born George Barrie added a whiff of exclusive connoisseurship to the Narberth legend in 1910, when he took up residence in the former Vauclain house. Barrie had already pledged himself to the comfortable values of the proud possessors of books and objects, such as J. Pierpont Morgan, a Barrie customer. Barrie called his house Puir-Hilch, and Barrie Road later built on a piece of his land is named after him. His wife, Renee Barrie, planted the carpet of periwinkle-blue Chionodoxa bulbs naturalized in the front lawn and still a joy to see in early April (as are thousands of February-blooming Siberian crocuses that lawyer Fletcher W. Stites planted in the front lawn of 413 Haverford Avenue).

The largest private home ever built here, Hobbs’s Belfield summer residence at the southwest comer of Narberth and Price avenues, was renovated by architect James A. Windrim soon after Belfield bought it in 1885. A member of the University of Pennsylvania Museum board of managers, T. Broom Belfield was a stern disciplinarian who had nine sons and three daughters. He insisted his sons bicycle daily from Elm to their Belfield foundry jobs at Broad and Spring Garden streets. Alexander C. Shand, the next owner of the house, called it Douglas-Garden. Only the garden, still remembered as an asset to the neighborhood, or at least some of it, remains, encircled by the borough’s largest apartment complex, the 110-unit Montgomery Court, built in 1939.

The Belfields before the turn of the century began the Christmas custom of lighting the towering hemlock on their grounds. Montgomery Court Apartments management continues this tradition every year and features eight hundred lights topped by a three-foot star visible from the railroad station. Carolers from the Methodist church usually gather beneath the tree. Another surviving tree, an umbrella ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) probably planted by Mr. Belfield, was named one of the top three of this species in a five-county area by Dr. John C. Swartley, who included it in his “social register” of “extraordinary trees” published by Morris Arboretum in 1970.

South of the Belfield house, Isaac H. Hobbs took advantage of Elm’s rolling terrain by placing his Gothic-style Richards house of ashy-pink stone at the summit of a long gentle southerly slope exactly where the ground levels off. The house was oriented toward the existing road (now Narberth Avenue), and its lot stretched back to Conway Avenue. Its stone gateposts can still be seen at 224 North Narberth Avenue.

Built speculatively opposite Richards’s in support of the Price plan, by a fashion industry pattern merchant, was a house bought in 1883 by widow Mary Ann Anderson Williamson. She lived there with her son William von Albade Williamson, clerk of the Third United States Circuit Court of Appeals, and his wife Maria Elizabeth McKean.

Two Williamson relatives had a finger in development at Elm—Mary Williamson’s brother-in-law and her husband’s first cousin. The brother-in-law, Percival Roberts, Sr., founder of Pencoyd Iron Works, looked after Mary’s welfare at Elm to the extent that he put his signature first among six names on a petition (1887) to widen her street, an Old Gulph Road extension. The cousin was George Brooke Roberts, then Pennsylvania Railroad president, who in 1892 accommodated the wishes of area residents by naming their station Narberth. Roberts did not originate that name, though he is often credited with doing so.

Norman Jefferies, the owner after 1911 of the Williamson house at 219 North Narberth Avenue (since razed for St. Margaret’s parking lot), installed there a copy of Independence Hall’s staircase. His wife, the former English actress Gwendolyn Jane Pinces, created an English garden showplace on the grounds. Mr. and Mrs. Jefferies were ardent supporters of the Narberth cherry blossom tradition. About 1927 Mrs. Jefferies opened a flower shop, now a dress shop run by her granddaughter at the same address on Haverford Avenue.

In 1886 the stove and cupola manufacturer William L. McDowell (president of Leibrandt and McDowell) commissioned a “mansion” on a small lot he bought in a sheriff’s sale. McDowell was a contemporary of Edward R. Price, and lived directly across Montgomery Avenue from him in a historic Price house. He set up legal “covenants and agreements” to obtain the imposing house he wanted, to ensure that he be paid ample ground rent, and to reclaim ownership if anyone defaulted. His deed conveyed the lot formerly owned by the “witch’s” daughter Elizabeth (with small buildings on it) to Isaac B. Culin of Philadelphia, a dry-goods-store clerk. Culin thereby agreed to construct within one year “a good and substantial three-story stone house of sufficient value fully to secure the said yearly rent described” (which ground rent could be extinguished only by paying ten thousand dollars to McDowell). Culin the same day conveyed this property, and its ground rent obligation, to the Joseph D. Ellis family of Fairmount, reserving to himself the task of seeing that the mansion was built.

Culin, probably of Swedish ancestry, built a stone mansion, Bel-Brya, only a few feet from a couple of log cabins that may be Swedish and are still in existence though transformed in their appearance. Bel-Brya still stands at 1236 Montgomery Avenue as D’Amore’s restaurant. Ellis’s partner in real estate, his brother J. Pemberton Ellis of Powelton Village, soon built an imposing stone house at Montgomery and Wynnewood avenues, since replaced by Wynmont Apartment.

Narberth’s most prominent family of Swedish colonial ancestry was the Justices. On part of Jacob R. Hagy’s former farm in Libertyville, silverware manufacturer F. Millwood Justice built a large house at 1104 Montgomery Avenue on land he acquired in 1889 and 1890. The sons of a prosperous hardware importer, “Mill” Justice and his brother Alfred were born in Powelton Village of a Quaker family related to colonial silversmith Philip Syng. When a street was cut through Justice’s property, it was called Stepney Place after “Mill’s” father-in-law, attorney Albert Stepney Letchworth, who lived here.

Alfred R. Justice, “Mill’s” brother, also lived in Narberth, eventually in the Richards house. His letter to his fiancee Jessie Lewis on July 26, 1891 (collection of Mrs. Jean Justice Collins), offers a vivid glimpse of early life in the depths of the countryside here:

The walk [with “Mill” and a cousin] served to stimulate our appetites and we enjoyed a dinner of vegetables from our own garden and some very good ice cream from the little store near by (not quite equal to Blank’s). Our garden is doing very well this season much better than last, and we luxuriate in all kinds of garden truck except corn, and we would have that had it not been for our cow, who broke loose one night and ignoring everything else except the strawberries completely destroyed our “Dreer’s early.” On Saturday afternoon I invited Will Ferris to come out and play tennis with me. He and Mill stood Mr. Forsythe and myself and we were very evenly matched. The day was so cool and pleasant that we thoroughly enjoyed it. In the evening we had music and chess.

The easy good manners of all concerned remind us that Elm village did not need Galsworthy. Elm had a Forsyte Saga of its own, in its early unhurrying days.

Edward Forsythe, mentioned in the letter, was an investment broker and manager of Des Moines Land and Trust Company dealing in “choice Western mortgages and school bonds” (1888 advertisement). He came of a Chadds Ford colonial family that claims many educators in its family tree, starting in 1799 with the legendary first male teacher at Westtown School, John Forsythe. Edward Forsythe was an Orthodox Friend and his wife Hannah Yerkes a Hicksite, which made for lively discussions in the spacious home they built at Elm in 1889-90 on Price Avenue facing Barrie House, according to their son Francis, who was born there. They had a large windmill on the grounds. The house still stands, embedded now in a housing subdivision. Everything about the house’s character, and about Edward Forsythe’s background, suggests that he built at Elm through the influence of Samuel and Bartram Richards. Both he and they had their land development offices in the Drexel Building.

Edward R. Price’s death in April 1887 signaled the end of 205 years of Price presence in the neighborhood, setting the stage for the immediate sale of two nearby tracts, the Furey/Ridgway/Vance tract and the Thomas/Gatchell/Macfarlane tract. By early 1888, the vitality and initiative that had marked the Price village episode became extinguished. Price’s original intention of selling his land in lots of not less than two acres was soon set aside. The contrived irregularity of the placement of Hobbs’s mansions quickly gave way to a tight grid plan with small building lots that partially surrounded and eventually encroached on the Godey’s Lady’s Book town.

The first developer of land bordering on Price’s village was lawyer and public figure John J. Ridgway, who purchased a 58.31-acre farm on the north side of Elm Station from the widow Maria Furey (the Philadelphia restaurant owner mentioned above) in November 1887 for seventy-five thousand dollars subject to two mortgages of twenty-five thousand dollars each and another of seven thousand dollars. In January Ridgway for one dollar turned the land over to his Real Estate Investment Company of Philadelphia. The acquisition launched the firm, of which Ridgway was president.

Active in Philadelphia reform politics, Ridgway represented the Eighth Ward in City Council, and became United States surveyor of the port of Philadelphia in President Benjamin Harrison’s administration. He knew real estate from his experience as Philadelphia sheriff, 1884-87. The Ridgways had Anglophile tendencies that would soon make a permanent imprint in names given to roads and to the eventual borough itself. Settled in this country since 1679, the Ridgways were interested in their Elizabethan and Jacobean family heritage in England and Ireland, where, according to Edwin Wolf 2d, the family has prominent early tombs.

Almost immediately after his firm had acquired the tract at Elm, John Ridgway mapped a grid plan for streets (that were later simply extended), gave them British names, fixed the size of building lots at about 50 by 150 feet, and numbered each (from 1 to 315). That arrangement has remained dominant, with few changes to this day. Windsor Avenue was created as the development’s only east-west street and main thoroughfare running along the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Price cowpath from the Price barn at Forrest Avenue to the meadow that started at Conway Avenue, and parallel to Haverford Avenue where the old Price water wheel was.

Ridgway named the new north-south avenues in alphabetical order starting at the western end of town with Alton (later dropped), Berkley, Conway, Dudley, Essex, Forrest, Grayling, Hampden, and Iona.

A Street Named Narberth

The single exception to the alphabetical listing is Narberth Avenue (east of Forrest), the only through street on the tract at the time. This street, an extension of historic Old Gulph Road, was just being widened when the portion running through the Ridgway tract was named Narberth Avenue. This name change comes to light in a deed of sale (Deed Book 320, p. 67) for a Narberth Avenue house on February 16, 1888. The deed says a “plan of land” had already been recorded for the tract. Thus “Narberth” made its first public appearance here as a street name, and on an important street.

Significantly this Welsh name was applied to the main street of the minuscule Godey’s Lady’s Book town that hereditary Welsh landowner Edward R. Price had founded in 1881 on his own property, adjoining the north side of Ridgway’s project.

There is no doubt that Ridgway came to his town-building task with Richards baggage. The name of the important street, Narberth Avenue, appears out of alphabetical order exactly as the main street, Atco Avenue, does in Richards’s town plan for Atco—it is almost as if the new name Narberth were being groomed to become the town name.

There is an old mansion, Ridgeway, located about three miles west of the town of Narberth in Wales. The National Library of Wales is unaware of any connection between a family of Ridgways and that mansion. It was already owned by the Fawley or Foley family in 1692, and connected with them until the 1860s, or later. Probably the existence of the well-known Ridgeway mansion at Narberth in Wales, however, would alone have been sufficient for Anglophile John Ridgway to introduce the Narberth name here, even if his family had no connection with the Fawleys or their mansion. By Richards’s standards, this would have been an acceptable approach, and Ridgway would have known this.

John J. Ridgway must have been aware that his banker-father had been a longtime close business associate of Samuel Richards’s uncle, Benjamin W. Richards, a Philadelphia mayor and acquaintance of Alexis de Tocqueville. Benjamin W. Richards and Thomas R. Ridgway were both founders of Girard Bank. (The Narberth branch bank recognized the founders at its twenty-fifth anniversary celebration in 1982.) Richards was its first president, Ridgway its second. If Samuel Richards saw John Ridgway at the funeral of Ridgway’s father in March 1887, or at the Rittenhouse Club to which they belonged, he could have told him about the large farming tract at Elm, ripe for development as a village.

Richards may even have had some part in suggesting that a new name be chosen for the street he lived on or for the town itself. With or without such help from Elm’s leading citizen, Ridgway chose lasting road names and sold fifty-seven lots, but built no houses on them. His first customer was engineer George Bowers of Philadelphia.

Sales were brisk, and houses started cropping up like mushrooms on the lots sold. The first house completed was for Otis Brothers Elevator Company president Alfred A. Lowry, 206 Forrest, still standing.

Another early arrival was German-born cabinetmaker Fred Bender, who built his own wooden house, still standing, at 217 Forrest assisted by his two woodcarver sons. The architect Oscar Frotscher put up a speculative Queen Anne Revival house at 115 Iona, which got him more residential work—for wood engraver David J. Hunter (109 Iona) and for drug and chemical firm executive Sylvester J. Baker. Mrs. Rebecca Elkinton Bacon’s imposing stone summer house, designed in 1888 probably by her architect-nephew and heir, Paul P. Elkinton, still stands at 106 Iona. Widow of Richard W. Bacon, Mrs. Bacon was a familiar figure on the new streets of Ridgway’s tract in her phaeton carriage, and later helped found the civic group.

Three Tract Developments

Narberth Park

The spirit and self-confidence of the merchant class are vividly reflected in the activity of a woman real estate developer, S. Almira Vance, born Sara Almira Chandler. This childless widow of a Philadelphia hardware manufacturer and dealer made rich by the post-Civil War building boom gamely launched from her Girard Avenue home a successful venture-capital scheme here in December 1888 at the age of sixty-six.

Just after inheriting a life interest in her husband’s large estate, Mrs. Vance bought Ridgway’s Real Estate Investment Company tract, and thus became the town’s largest developer. Some seventeen lot sales were being negotiated when she took over the tract for $46,500 subject to mortgages of forty thousand dollars. Her lawyer at the time, also engaged to settle her husband’s estate, was J. Alexander Simpson, Jr., later an associate justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. He supported her efforts here for many years. His parents, married sisters, and brother soon became prominent residents at Elm, though none ever lived on the Vance tract.

During the early days of her stewardship, the Vance project received the name “Narberth Park” on a plan of lots. The name appears on her first deed of sale, made to William Stanton Macomb in January 1889 (Deed Book 331, p. 240). Ridgway, who, with his wife Elizabeth Fry, retained small holdings here until 1892, probably proposed the name Narberth Park to Mrs. Vance. She gave it that name immediately after buying the land, presumably before she became familiar with the area. In any event, the name was crucial and, for Ridgway, may have represented the second milestone (after naming Narberth Avenue) in a strategy to have Narberth chosen as town name.

“Crystal Lake” also has a Ridgway ring to it. Surely Ridgway would never have overlooked naming a body of water on his land. Just as Almira Vance’s preference for pert pansy flowers led to her wearing gold and diamond pansy brooch and matching earrings, so Ridgway may have cottoned to gleaming crystal as an image. Besides, cheerfulness appealed to many Victorians, and the Crystal Lake name certainly put a cheerful face on a problem (a swamp) that would vex local developers for nearly two decades.

Probably no Narberthian alive remembers the name Crystal Lake. Yet the location of the bed of a lake so named is described in two deeds (Deed Book 371, p. 331, of 1892; Deed Book 398, p. 481, of 1894). As described, its position was within a rectangle extending lengthwise 700 feet from Haverford Avenue north along Indian Creek. By 1895 Crystal Lake had been piped underground, but a smaller south-side lake still existed. This lends credence to an oral tradition (related in 1980 by Anne Berry) stating that Indians gave the name Swan Lake to a body of water they frequented extending from today’s playground to Elmwood Avenue on the south side. William Penn mentioned seeing numerous wild swans in his new colony, and the Indian name Karakung (Cobbs Creek, of which Narberth’s Indian Creek is a tributary), means “place of wild geese.”

Almira Vance’s banker was William M. Singerly, president of Chestnut Street Trust Company and publisher of the Philadelphia Record. He and other bankers aided this early phase of local development as mortgage-lenders. Also, a written agreement stipulated that Singerly handle promotion of Mrs. Vance’s tract at certain specified times.

Meanwhile Almira’s agents in land sales for her Narberth Park development were William R. Bethell, husband of her younger sister Emily, and their youthful son, lawyer-to-be J. Uhle Bethell. J. Uhle Bethell had already purchased from Ridgway one of the tract’s more desirable locations (eventual site of St. Margaret’s Church and rectory).

The thorn in the rose for Almira was that she and J. Uhle Bethell were co-executors of her husband’s estate, and although Bethell had charge of seeing that she got what inheritance was due her, he failed to fulfill that task. Almira was left holding worthless promissory notes. Her apparent answer to this was her permanent departure for New Rochelle, New York, out of her nephew’s orbit. Before this happened, builder Warner Davis of Woodbury, New Jersey, became associated with the Bethells on the Narberth Park development project. That trio, as Bethell, Davis and Bethell (with Emily succeeding her soon deceased husband), began erecting eye-catching Queen Anne Revival houses for Almira’s customers and also speculative houses on lots they themselves occasionally bought from her.

The project sailed along at full tilt: on November 13, 1890, the Philadelphia Public Ledger reported that “Davis and Bethell had put up and sold twenty-seven dwellings on the north side of the railroad, and at this time are completing an average of one a month.” Home-buyers by then included Major Jeremiah W. Fritz, celebrated commander of a Civil War battalion of the Union Army, 201 Essex. Fritz’s home with rambling porches later was enlarged as Miss Posey’s boardinghouse, which for many years catered to a summer clientele. Finally between the two world wars it became Windsor-Essex Inn, a cozy informal residential hotel and dining room. A twenty-three-unit apartment, Essex Manor, replaced it in 1962. Another buyer (at 201 Forrest) was commission broker Frederick H. Harjes. The rotund turreted house at 115 Dudley, which Francis P. Dubosq of the jewelers’ family bought, and houses at 119, 121, 123, and 125 Windsor were later used by a filmmaker as a movie set. On the tract’s most scenic site at Wynnewood Avenue was its largest (summer) house, owned by Margaretta T. Fuller, wife of drover Alfred M. Fuller. During publisher James Artman’s ownership in the teens and twenties it became a year-round home, and everyone in the community was welcome to swim and skate on the lake there. The house later became Lakeview Apartments (with a duck pond), replaced by Narwyn Lane subdivision about 1960.

Construction at Narberth Park entered a quieter phase after Mrs. Vance moved to New York. Another developer, the Clothiers, bought her holdings (150 lots) in December 1894. The well-connected, if inexperienced, Clothier partners, cousins, must have boosted hopes of residents anxiously awaiting the court’s decision on borough status for Narberth.

An obvious drawing card in their enterprise was the active participation of young Albert E. C. Clothier, who “knew the ropes” in the sense that he was the son of the business partner of Edwin Fitler, a millionaire rope manufacturer who had been mayor of Philadelphia a couple of years before and a “favorite son” nominee for president in ’88. Albert and John B. Clothier, of a family predating the department store Clothiers in Philadelphia and no kin of theirs, settled here and joined forces with local builder George O. Goodman under the name Goodman and Clothier.

Predominant among the varied styles of Goodman and Clothier houses were buildings with a medieval character having steeply sloping roofs. They also built the house with country-Georgian details now occupied by Mapes’s (formerly Davis’s) Store.

The South Side

The south-side story picks up in November 1888, when C. Stephenson Gatchell of Haverford bought 30.556 acres of William Thomas’s land for forty thousand dollars. The same day, Gatchell heavily mortgaged this land and sold it to builder Walter B. Smith, who next sold it, with full acreage intact, to builder and civil engineer Charles William Macfarlane of Philadelphia in April 1889 for twenty-five thousand dollars.

Macfarlane initiated his own systems of drainage and water supply, erecting a picturesque water tower. By August 1889 Macfarlane had entered into a preliminary agreement to convey land to the Pennsylvania Railroad provided it be used exclusively for a “passenger station and appurtenances” to be constructed within five years. This small wooden shelter (in modern times housing the ticket agent’s office) survived the larger and older stone station across the tracks by a generation. This was the wooden structure that SEPTA leased from Amtrak and replaced in 1981 with a new inbound station of steel frame with glazed marquee, “monumental” stairs, ticket office, and rest rooms (Ueland and Junker, architects).

Macfarlane sold his first house (122-124 Elmwood facing the station) to Grove Locher in April 1890 for $6,600. Macfarlane developed a compact grid plan for 128 building lots, and named Elmwood, Woodside, Thomas, and Readrah avenues. Only two south-side roads are older: Rockland Avenue laid out by farmer James Sullivan before 1878, and Wynnewood Avenue (now called East Wynnewood Road), 1878.

On November 13 the Public Ledger reported that C. W. Macfarlane had already finished eleven houses, was building two more, and “selling them as rapidly as they could be completed.” Among the earliest Macfarlane homeowners was Samuel Swaim Stewart, the first established banjo maker and banjo music publisher with an international clientele. Another early home-buyer was the energetic Wilmington-born lawyer J. Alexander Simpson, Sr. An expert on election law, he had served as counsel in many leading political contests in the courts and was state register of wills in 1873.

Macfarlane’s development of his own lots (he sold twenty-six) continued at a rapid pace until early 1892, then slackened. One crucial event had narrowed Macfarlane’s prospects and removed the drainage and water supply systems from his control. C. Stevenson Gatchell defaulted on his mortgage late in 1891.

Spring Garden Insurance Company, a fire insurance firm founded in 1835, acquired all of the tract (except “released” lots) at sheriff’s sale for five thousand dollars in March 1892. The company president then was William G. Warden. Board members included Addison Hutton (“Quaker architect of Bryn Mawr” and designer of Philadelphia’s Ridgway Library), hat manufacturer John B. Stetson, and banker William Wesley Kurtz. The insurance company thereafter maintained the streets and lights, looked after drainage and water supply units it now owned, and sold thirty-eight lots through 1914.

The last-to-be-developed, large south-side section of the borough, marked “C. S. Wood Estate” on the 1895 borough map, stayed a while longer in the hands of executors R. Francis Wood, John H. Packard, and Charles Stewart Wurts. Finally it received the name “Narberth Grove” in an 1899 plan of lots. Here stands the borough’s oldest tree, an enormous white oak, patrician, aloof, about four hundred years old, at 303 Chestnut.

Belmar

Belmar was the name of a third tract-house development before Narberth became a borough. The November 13, 1890 Public Ledger account described its location as “back of Elm.” The Elm Land Improvement Company acquired Belmar’s fourteen acres on December 4, 1890. This strip of land gave a north-south thrust to Elm’s layout, and an extension of Essex Avenue northward became its principal street. Prime movers of Belmar were some of Elm’s most civic-minded and energetic citizens: J. Alexander Simpson, Sr. (first to buy lots), his son-in-law James Chadwick, A. A. Lowry, and Charles E. Kreamer. Belmar’s principal residence was Chericroft, built for J. George Bucher, the president of a galvanizing products manufacturing firm and a Presbyterian elder. The sixty-unit Narberth Hall Apartments replaced that large home in 1929. Belmar disrupted Price’s Lady’s Book village plan for large lots more than anything till that time. Belmar’s major cross-street, Sabine Avenue, opened in 1894, a year after Narberth Public School was constructed at the intersection.

Five Churches

In the years when residents were seeking organization as a borough, they were also coming together by systems of belief and practice. Thus the Public Ledger, reporting on the progress of the three tract-house developments at Elm, was able to declare on November 13, 1890:

The people of Elm are bestirring themselves in the direction of securing churches, and a movement is under way that promises well for an edifice for the Baptists. It is said that N. [sic] S. Hopper, a Philadelphia broker, has agreed to subscribe ten thousand dollars toward the building. At present services are held in a vacant dwelling. There is some talk, too, of a Presbyterian church and subscriptions are about to be solicited for the establishment of such a church. It is likely that the ground required will be donated by a lady deeply interested in the growth of Elm.

The Baptists did indeed build the first church, the Presbyterians the second, and the Methodists a third, all before 1895. Thus by the time the borough came into existence, Narberth already was a place recognizable by its houses of worship. Two more churches, Catholic and Lutheran, soon rounded out the picture. Like Merion Friends Meeting, the Baptist, Presbyterian, and Catholic churches are located on Edward ap Rees’s original Merion Welsh land grant (1682), while the Methodist and Lutheran churches occupy land similarly granted to Hugh Roberts in 1681. In 1980, as much as ever, Narberth’s five churches continued to draw the nearby residents together. Church bells and recorded hymns are heard regularly. Additional binding together comes from the Main Line Reform Temple and All Saints Episcopal Church, which, like the Friends Meeting, stand just outside the borough perimeter.

Narberth’s only south-side church is Baptist, located on the former 102-acre plantation of William Thomas, a devout Baptist. Several factors favored a Baptist church here, besides the previous ownership of the land. Prominent Baptists Harry S. Hopper and his wife Harriet M. Bucknell (of the Bucknell University family) moved into their new home Pennhurst in nearby Fairview. Baptist minister the Reverend Thomas C. Trotter, Sr., settled in Elm’s south side. Also, clergy from the Baptist Publication Society started an enclave in Elm’s south side that supported community progress and provided community leadership. The Baptist enclave, which included several ministers, supplied Narberth’s first public school board president, the English-born Reverend Philip L. Jones. A Baptist Publication Society editor, he was formerly pastor of South Broad Street Baptist Church. The Reverend Dr. C. R. Blackall, an author and editor of Baptist Superintendent, made his home in Narberth. His wife, known professionally as Mrs. C. R. Blackall, was the first editor of the Narberth Civic Association’s Our Town newspaper and originator of the 1914 historical pageant. Another was the Reverend Elim A. E. Palmquist, Woodland Baptist Church pastor, Philadelphia Council of Churches organizer, and member of the Philadelphia mayor’s crime commission.

After services and Bible school began in autumn 1890, the Baptist mission was organized and linked with the First Baptist Church of Philadelphia. In June 1891 Harry S. Hopper bought a lot from Macfarlane, agreeing that a “substantial stone” church and Sunday school be built there within three years, the deed says. The cornerstone was laid October 10. Prof. William B. Godfrey directed the music and a Miss Caldwell sang the “Psalms” at the formal opening in April 1892. The Public Ledger noted that $4,500 of the church’s $11,000 cost had already been paid. Church seating capacity was 245; and basement Sabbath school room, 125.

Following the Reverend Harold Kennedy’s installation as pastor, the mission gained independent status as the Baptist Church of the Evangel. It had 130 members by 1907. In 1923-24 an entirely new Gothic church (Victor D. Abel, architect) was built adjoining the old sanctuary, which is now a thrift shop. Of the ten pastors who succeeded Harold Kennedy, the Reverend James C. Flanagan was the first to combine his ministry with a full-time job in business.

Journalistic speculation that “a lady deeply interested in the growth of Elm” would donate land for a Presbyterian church proved overly optimistic. In May 1891, nearly six months after that Public Ledger report, the woman in question—S. Almira Vance, developer of the Narberth Park tract and daughter of a prominent Presbyterian minister—sold land at Windsor and Grayling avenues to Narberth Presbyterian Church trustees for twelve hundred dollars. Nonetheless Mrs. Vance probably did greatly welcome the idea of this church on her tract.

The Presbytery of Philadelphia-North accepted the proposal for a Presbyterian church here because none existed between Gladwyne and Overbrook. It next appointed a committee, which met in June 1891. On that occasion the group received nine members, was declared a full-fledged church, elected five trustees, and named two elders. Services began in a vacant house at 116 Elmwood. The charter was recorded July 6, and a frame structure dedicated in November.

Dr. William Young Brown’s installation as first pastor took place in 1894. After fire destroyed the wooden church, the cornerstone of a new church was laid in January 1897. Of the opening service in the new church on September 9, the Public Ledger reported that the Holmesburg granite structure was built substantially, and was keyed to the demands of an increasing population rather than the short-range needs of its small flock. Designed by architect J. Cather Newsom and built by Benjamin Ketcham’s Sons, the structure drew praise for its picturesque exterior, its tiling, oak paneling, and lofty tower with thousand-pound bell. The name Conrad F. Clothier (Mayor Edwin H. Fitler’s business partner) led off the list of memorial windows designed by Alfred Godwin and William Reith.

Pew rents were abolished in 1912. When membership reached five hundred in 1925, a Gothic addition (F. G. Warner, architect) was built and dedicated. Membership—in the six hundreds since 1929—rose to 737 in 1938. Assistant ministers and student assistants had been added during the pastorate of the Reverend Bryant M. Kirkland, and membership totaled 938 in 1946, when he was called to New York’s Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church. It peaked at 986 during the Reverend Robert J. Lamont’s pastorate in 1949. Since then the figure has settled into the eight hundreds, except for a slight dip during the sixties. An extensive church addition with Gothic entrance facade (Clarence H. Woolmington, architect) was built in 1955-57. During the current ministry of the ninth pastor, the Reverend George Callahan, the church ventured into charismatics. Narberth’s last three mayors came from this congregation, as well as at least three foreign missionaries and ten ordained gospel ministers. The newest of these is Narberth-born William F. Dean, ordained and installed as this church’s assistant pastor in 1981.

Narberth’s only church transplant is Methodist. Beth-Raffen Methodist Episcopal Church was originally founded in Fairview in 1884, eight years before a decision was made to build its permanent building here. Narberth got the church thanks to the bequest of a devout divorcee, Mary F. Thompson, and strenuous efforts on the part of two Elm community leaders, J. Alexander Simpson, Sr., and Charles E. Kreamer.

The initiative of four Lutherans spearheaded the founding of Beth-Raffen. Members of St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in Ardmore— Samuel B. Tibben, August M. Bornmuller, George G. Holliday, and Samuel F. Tibben—signed a statement in March 1881 declaring a need for a Lutheran church and Sunday school for themselves, their families, and their neighborhood. They offered building stones and a lot on Conshohocken State Road one mile south of Mill Creek, but to no avail. On their second try, they won Methodist approval.

The first Methodist class meeting took place in October 1884, with Mary F. Thompson of Fairview and her adopted daughter Priscilla N. Thompson in attendance. Services were regularly held in farmer Samuel B. Tibben’s Fairview home until a wooden church was built on the Tibben lot. The Beth-Raffen name and a constitution were adopted in 1885. Attached to what is now called the Gladwyne United Methodist Church, Beth-Raffen Mission came into the orbit of Mary F. Thompson’s varied Methodist benefactions at her death in 1888. Her gift of fifteen hundred dollars “to be used as they shall deem best” is believed to have clinched a decision to build a permanent structure.

J. Alexander Simpson, Sr., and Charles E. Kreamer thought it ought to be sooner rather than later—and at Elm. By 1892 banker Kreamer was running the Belmar tract-house project of the Elm Land Improvement Company, which had much to gain from securing a church as focal point, just as the other two, bigger, competing developments here had done. They won their goal by becoming active participants in the life of the mission, then still under the wing of the mother church in Gladwyne. In 1892 J. A. Simpson, Sr., was elected a Beth-Raffen trustee and placed on a site-search committee. In less than two months his committee report of a desirable lot at Essex and Price avenues was adopted. Appointed to the building committee were Simpson, a Simpson son-in-law, and Kreamer. A raging fire destroyed the nearly completed church. Finally finished by a new builder under architect D. Judge DeNean’s supervision, the structure was dedicated in September 1895. Independent status in 1897 brought a new name, Narberth Methodist Episcopal Church.

By 1925 every inch of that “little church on the hill” seemed crowded by 291 active members and 287 Sunday school pupils and teachers, so a new church in the late English Gothic style (Alexander Mackie Adams, architect) was planned. Pledges were taken to meet costs, and construction was to start in five years on three acres of Barrie land purchased across from the old church.

Then suddenly, soon after the ground-breaking, the Great Depression of 1929 struck. Plans went ahead anyway. Eventually not only did the local bank that held the construction funds fail, but some of the church’s active members died or were transferred. Still the people completed their task. The church, with windows by H. L. Smith Company, was dedicated in September 1930, and a mortgage-burning ceremony was held in 1951. Continuation of this costly project in the face of many obstacles is probably Narberth’s most heart-warming Depression story.

In 1946 the congregation presented an amplification system for the tower carillon to honor both living and deceased members who had served in World War II (the deceased included Robert Compton, William Haywood, Charles Latch, and C. J. Rainear 2d). Chimes and hymns vary according to the church season and patriotic holidays. They play daily at noon and six-thirty in the evening and Sunday mornings.

While still attached to Gladwyne, this church had seven ministers, and subsequently twenty-three ministers, including the present pastor, the Reverend John L. Taylor. Two Narberth mayors (then called burgesses), namely, Fletcher W. Stites and Henry A. Frye, came from this congregation, now known as the United Methodist Church of Narberth.

The Reverend Richard F. Cowley celebrated the founding-day Mass of St. Margaret’s Catholic parish on Christmas 1900. For the occasion the new parishioners gathered at Derlwyn, the twenty-room residence of the church’s first and long-time benefactor, stockbroker Nicholas H. Thouron and his wife Anna Dutilh Smith Thouron.

Regular Masses were first held in Narberth’s Elm Hall fire station. By 1901 area Catholics totaled 276. The Maguire’s Court-Hey, a picturesque estate on Wynnewood Avenue (formerly Mrs. Fuller’s, later Lakewood Apartments, now Narwyn Lane subdivision), was officially deemed the most desirable location for a church. It was unavailable.

Father Cowley settled the site problem by buying a Narberth Avenue triple lot, which J. Uhle Bethell had purchased in June 1888 before his aunt Mrs. Vance took over the Ridgway tract. Publisher Samuel Irvine Bell had lived in the turreted Queen Anne Revival house that Davis and Bethell built there. That residence became and still is the rectory. The building of a church occurred in stages. A basement church was finished in 1902. Dedication of the English Gothic-style church of Avondale granite with Bavarian stained-glass windows took place on a snowy day in March 1914. F. F. Durang designed the church, and parishioner John Flynn may have designed the crypt.

By 1929, in response to outbreaks of bigotry during the Smith-Hoover presidential campaign when klansmen had marched up Woodbine Avenue (in the parish and in the Narberth postal zone, but not in the borough) to light a fiery cross, St. Margaret’s parishioner and advertising executive Karl H. Rogers started the Catholic Information Society of Narberth. This “Narberth Movement” published (until 1942) widely circulated interfaith booklets with catchy titles that aired Catholic doctrine on a “take it or leave it” basis, without argument. The movement went national and was copied overseas.

In 1937 James J. Duffy became the first of fourteen parishioners ordained a priest. By 1979 the congregation comprised 1,250 families or about thirty-five hundred persons. After one year as the seventh pastor, Monsignor Francis Bible Schulte (the third consecutive monsignor to run the parish) was ordained an auxiliary bishop to John Cardinal Krol of Philadelphia in August 1981. The president of the Middle States Association accrediting agency for all colleges and schools in the region, Bishop Schulte was the first priest to hold the title. He was also the first pastoral auxiliary bishop of Philadelphia to be posted in Montgomery County, the first in a Main Line community, and Narberth’s first bishop. Auxiliary bishops go where the people are. This parish has long had a reputation for high attendance (2,300-2,500 on a typical Sunday), large numbers of people taking communion (more than a hundred thousand communion wafers used here annually), and one of the strongest records of financial support of any church in the archdiocese.

Two other bishops, both exiles, have resided in St. Margaret’s parish (at the Sisters of Mercy mother-house in Merion): namely, George J. Caruana, Archbishop of Malta (1947-51) and Joseph M. Yuen, Bishop of Chumatien, Honan, China (1956-69). Chaplain of that motherhouse until 1940 was the Reverend Francis Brennan, who, as a cardinal posted in Rome in 1968, attained the highest Catholic church office ever held by an American.

Since 1884 local Catholic children had attended “University School” run by Sister M. de Mercedes in a house on the grounds of the Sisters of Mercy, Merion. Not until 1922 did Father Cowley purchase a house at 209 Forrest to be used for education, making it official that a parish school was located in Narberth. Into it he put forty-eight pupils for a year until he constructed a school (designed by William Webb Donohoe of Donohoe and Stackhouse, architects) on the site.

In 1925 the cornerstone of St. Margaret’s School was laid, dedication occurring the next year. One hundred and two pupils were enrolled then, and Sisters of Mercy from Merion conducted the eight grades. Dennis Cardinal Dougherty presided over a ceremony for the first full-year graduates of the school in 1927. During the Reverend James F. Toner’s pastorate (1938-53) parochial pupils reached the three hundred mark. Monsignor Joseph M. Gleason in 1968 constructed a new school (Henry D. Dagit & Sons, architects) and convent, turning the old school into a parish center. From 1969 to 1973 the old school served as religious school and synagogue of Temple Beth Am Israel. Since 1967 a St. Margaret’s school board appointed by the pastor has functioned. In 1980-81 parochial school enrollment was 288.

Narberth acquired its Lutheran Church of the Holy Trinity in 1921. The first meeting, attended by eight persons, took place in October, a month after the idea of founding the church was born. Next a canvassing committee obtained eighty-five charter members, and the first service took place at the former YMCA building in December. Formal organization followed in January 1922 with ninety members enrolled. Sunday school started in March.

After the first pastor, the Reverend M. E. McLinn, arrived a year later, overcrowding at the YMCA prompted the formation of a building committee to purchase land. Anne Berry recalled having attended some evangelical meetings in a tent that covered the present Lutheran church site at the southeast comer of Narberth and Woodbine avenues. A springtime 1924 ground-breaking for this hilltop Gothic church of gray stone, designed by architect George Baum, was followed by dedication in May 1925.

The next pastor, the Reverend Cletus A. Senft, spent his entire thirty-six-year ministry at Holy Trinity. A combined parish house and parsonage annex was dedicated in 1940. The church greatly expanded its membership after Pastor Senft returned from a leave of absence as a navy chaplain with the Seabees in the South Pacific. Various parish groups (the church women, church school, choir, and youth organizations) were in existence almost from the start of this church and developed more fully in the fifties. The peak years of membership were 1959 through 1961 with 552 persons. The Reverend Kenneth F. Frickert was the next pastor. Under the fourth and present minister, the Reverend Orion A. Eichner, Holy Trinity membership was 441 in 1980. Fifty-three percent lived in Narberth, and the pastor said that an unusually large percentage of them have had a longtime association with the church. Since Holy Trinity is located near the scene of an arson fire that destroyed several homes on April 20, 1981, it served as headquarters for dispensing needed help and supplies to the homeless for some time afterward.

Public Schools

A two-story public school building was constructed of stone from the designs of D. Judge DeNean, an Ardmore architect born in Maine, and opened by the Lower Merion Township School District at the northeast corner of Sabine and Essex avenues in 1893. The School Board of the new borough took charge of the school facility in September 1895. At the time there were forty-four pupils in eight grades, all taught by Miss Allie G. Plank and one assistant. The first Narberth High School commencement, in 1909, had four graduates. Rapid population growth led to a $55,000 bond issue for modernization effective autumn 1916. By 1920, 592 pupils were enrolled and a three-acre playground was added to the school plant.

Narberth High School granted eighteen diplomas in 1922. But controversy over its future swirled. A defeated bond issue for a separate high school building led to the sending of high school pupils to Lower Merion in 1923. Kindergarten through grade eight had an enrollment of more than five hundred in 1930. That year W. James Drennen became supervising principal, a post he held for twenty-one years. In 1931 the school Press Club started publishing the prize-winning Sun Dial newspaper. At that time the modernization of the building housing the intermediate and upper grades by architect Victor D. Abel provided new floors, new stairways and partitions, and a new floor plan. Grades six through eight, based on a modified junior high school program, and the intermediate grades four and five comprised the Upper School. Its faculty consisted of four intermediate-grade and eight junior-school teachers, and it had a secretary and two custodians. The Primary unit, comprising kindergarten through third grade, had eight teachers and a physical education instructor. Its stone building, connected to the east end of the Upper School by a passageway leading to the cafeteria, was modernized in the forties.

Still frequently discussed in Narberth are two historical pageants that Narberth Public School presented: “A Nation Rises,” held in Narbrook Park for the Constitution’s 150th anniversary (1938), and “A Community Rises”, which celebrated the borough’s fiftieth anniversary (1945).

Starting in 1961, students in grades seven and eight as well as grades nine through twelve went to Lower Merion secondary schools. A new school (Chapelle and Crothers, architects, John Donovan, Inc., builder) for kindergarten through sixth grade was built in 1961-62. Narberth Public School merged with the Lower Merion School District in 1966. It closed in 1978 because of declining enrollment. The building was recycled for private business use, and the children were bused to other Lower Merion schools.

Fire Company and Police

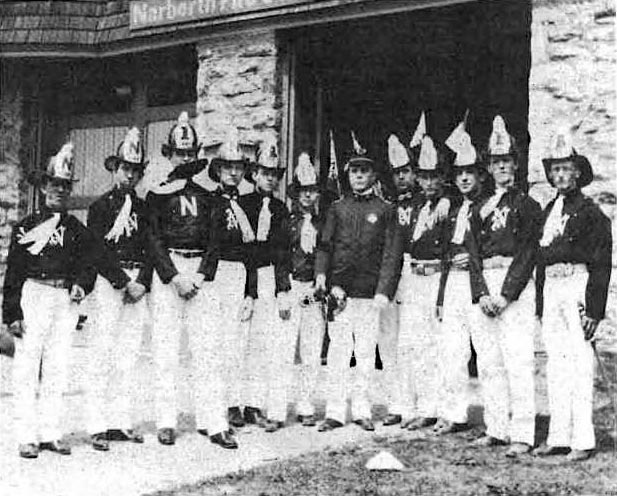

Narberth Fire Company has served as a volunteer group since October 1896. The event that ignited community attention was the Narberth Presbyterian Church fire in January 1896.

The arrival of the first mobile fire apparatus (which lasted seventeen years) prompted the first fire company parade in 1897. Two years later the fire company built Elm Hall on Forrest Avenue, which it occupied sixty-one years, renting the upstairs to Borough Council. It acquired the first motorized fire apparatus in 1913. The fire company’s district included Merion, Penn Valley, and Wynnewood, more of its calls being made in those areas than in the borough.

The worst Narberth fire occurred January 1940 in Ricklin’s Hardware Store; it destroyed a quarter-block containing seven stores, twelve apartment units, and some business offices at Essex and Haverford avenues, and made forty-two persons homeless. An April 20, 1981, arson fire blazed through nine brick rowhouses in the two hundred block of Woodbine Avenue, consuming five structures and leaving twenty-one persons homeless, including a newborn infant. Mayor J. J. Eyster collected $8,000 and distributed it in checks to these families.

Narberth’s fire chief from 1898 to 1910 was a Washington-born French count, Tristan B. du Marais. Dr. Albert C. Barnes, one of America’s leading art collectors, had a close association with Narberth Fire Company. It came about, said Miss Violette de Mazia, the Barnes Foundation educator, through Albert H. Nulty. Nulty began his association with Dr. and Mrs. Barnes as their coachman in Overbrook, and was a Narberth fireman. Dr. Barnes, interested in Nulty’s work, attended fire company social gatherings, served on its board, and was an honorary vice-president.

As the picture-hanger at the Barnes Foundation, Nulty worked closely with the modern French master Henri Matisse, installing the Matisse murals there. Dr. Barnes sent Nulty to the Detroit Institute of Arts for apprenticeship to a renowned German restoration expert. Afterward Nulty became art restorer and curator at Barnes, personnel head, and, after Dr. Barnes’s death, a trustee of the foundation.

A bronze plaque outside the firehouse honors Borough Council secretary and fire chief Charles V. Noel, who perished the day after Christmas in 1937 fighting a St. Charles Seminary fire. Noel was the only Narberth fireman to lose his life in the line of duty. Dr. Barnes suggested the memorial, then commissioned Barnes Foundation art student Marcella Broudo to make it. In memory of Albert Nulty the Barnes Foundation gave Narberth Fire Company its first rescue truck, housed in 1958.

A Narberth Fire Company auxiliary, Mulieres, began in 1930.

Burgess Richard H. Wallace, reporting to council in 1905, declared the borough “notably free from destructive fires and house robberies.” Yet he cited a need for “a mounted official” to patrol late afternoons and nights. In August 1914 the first full-time policeman, Daniel J. Hill, was hired at a six-hundred-dollar annual salary. In 1922 Narberth’s police force came under the supervision of the Lower Merion Police Department by a cooperative agreement making available such centralized services as the township jail, detective work, police instruction, and communication system. This arrangement continues, a flurry of talk in 1979 about a borough-township police merger having subsided.

Rapid Growth, 1900-1930

The period 1900-10, sometimes called the “Silent Decade,” was one of preparation, optimism, and nostalgia in Narberth, as elsewhere. New people of prominence in the borough were associated in some way with urban machines, Alexander C. Shand, chief engineer of the Pennsylvania Railroad and one of the nation’s foremost civil engineers, and James Artman, founder of Chilton Publishing Company. Artman had foreseen the possibilities of motor transport, and he seriously entered the automotive field with the Automobile Trade Journal in 1899. Road-building contractor Theobald Harsch had begun employing Italian immigrants and housing them in dormitories he built in Narberth.

Growth was rapid during the borough’s first decade. The number of dwellings passed twelve hundred and about six miles of roads existed. Families with young children were numerous among some nine hundred inhabitants in 1900, as were live-in servants (about forty-six whites, forty-five blacks).

Miss Mary K. Gibson of Wynnewood acquired a large wooded lot at 20 Sabine Avenue from the Price estate in 1906 and built on it Holiday House, a place where poor city children referred by the Octavia Hill Association and other settlement houses were brought to enjoy fresh air and summer sunshine. In 1921 Holiday House was run by the Evangel Circle of the King’s Daughters, sponsors of its endowment fund drive and an affiliate of Narberth’s Baptist church. Robert Grant, a guard at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, said that he fondly recalled Holiday House piano music, Bible stories, and games he played while a childhood guest there about 1920.

Professor Samuel P. Sadtler, the famed chemist, just after the turn of the century moved a Colonial Revival brick house with an 1892 datestone to its present location at 243 North Wynnewood Avenue, adding it to a smaller house. In 1906 Sadtler’s neighbor Stephen Paschall Morris Tasker led an expedition from Hudson Bay across Northern Labrador to the Atlantic Ocean and wrote a book about it (Steve Patrols More Territory, 1936).

Narberth baseball traditions date from the launching of the Main Line League in 1908. Baseball dominated the local sports scene for a decade before increased housing construction gobbled up the sandlots. Usually called the “oldest store in Narberth,” Howard E. (“Pop”) Davis’s general store (Mapes) opened its doors in 1908, and before long attracted sports enthusiasts. A mainspring of recreational life from 1908 to 1920 was the YMCA, handsomely housed on Haverford Avenue.